dialogue BLOG

Personal insights and opinions from Gensler’s global experts on how design is shaping the future of cities. Subscribe to our dialogue Now newsletter to get regular updates sent directly to your inbox.

1076 Items

When Rivers Rise and Wells Run Dry: Designing Water-Resilient Cities

Climate change is making floods and droughts more intense — but designers have solutions that can limit the damage.

December 24, 2025

|

For People to Stay, They Need Places to ‘Go’

Public restrooms are essential urban infrastructure that help people pause, linger, and enjoy city life.

December 22, 2025

|

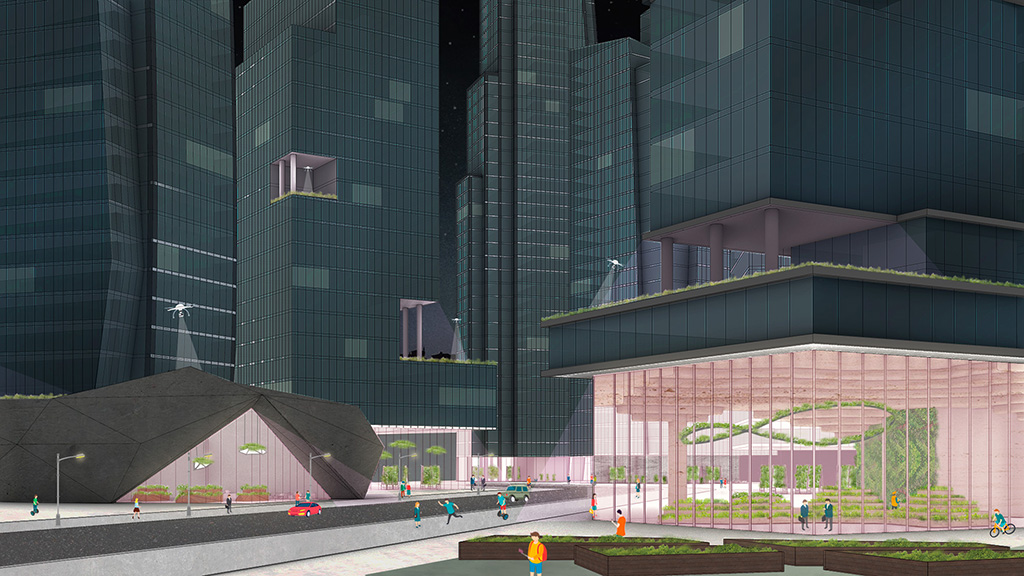

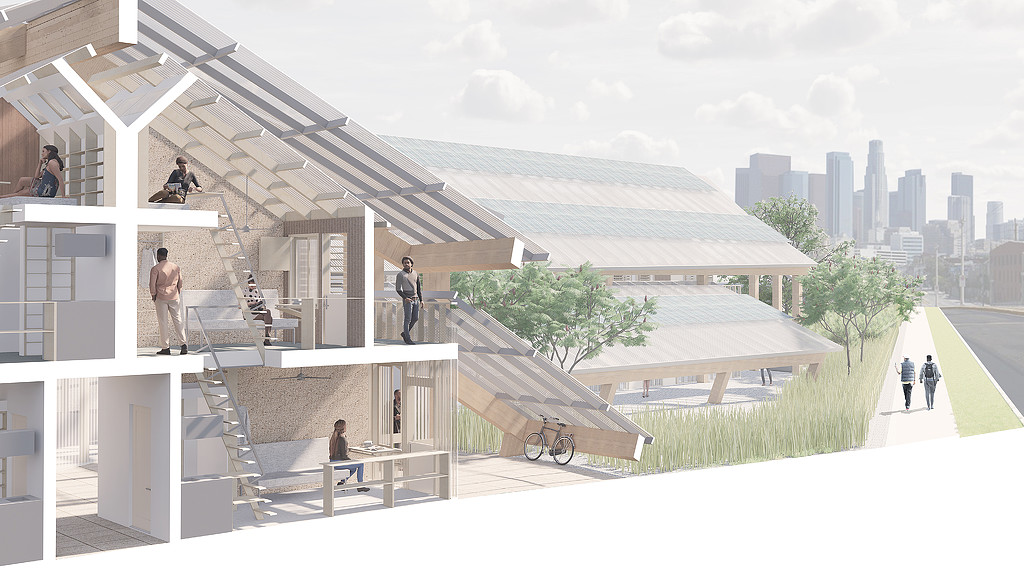

Beyond Blueprints: What Happens When Students Redesign Cities

The urban planners and architects of today and tomorrow must offer strategies that tackle complex, cross-cutting urban challenges with creativity.

December 19, 2025

|

Seattle’s Office-to-Residential Future: How Policy and Design Will Transform Downtown

A combination of code changes, design expertise, and market conditions is proving that now is the time to start planning new housing in Downtown Seattle.

December 16, 2025

|

Trends to Watch: What’s Next for Airports and Aviation

Gensler’s Aviation leaders take a closer look at the trends shaping the future of travel, and what’s next for the industry.

December 09, 2025

|

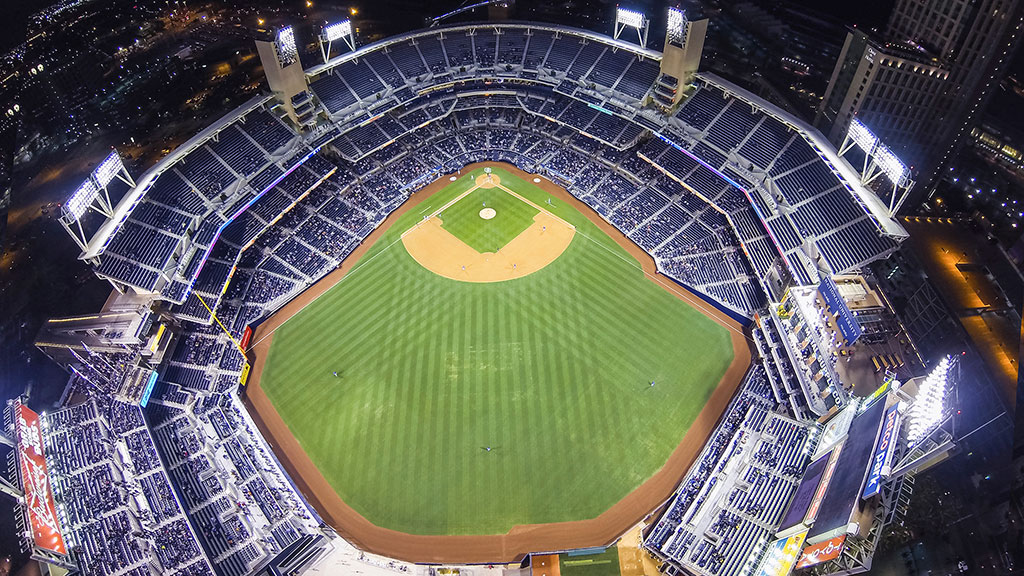

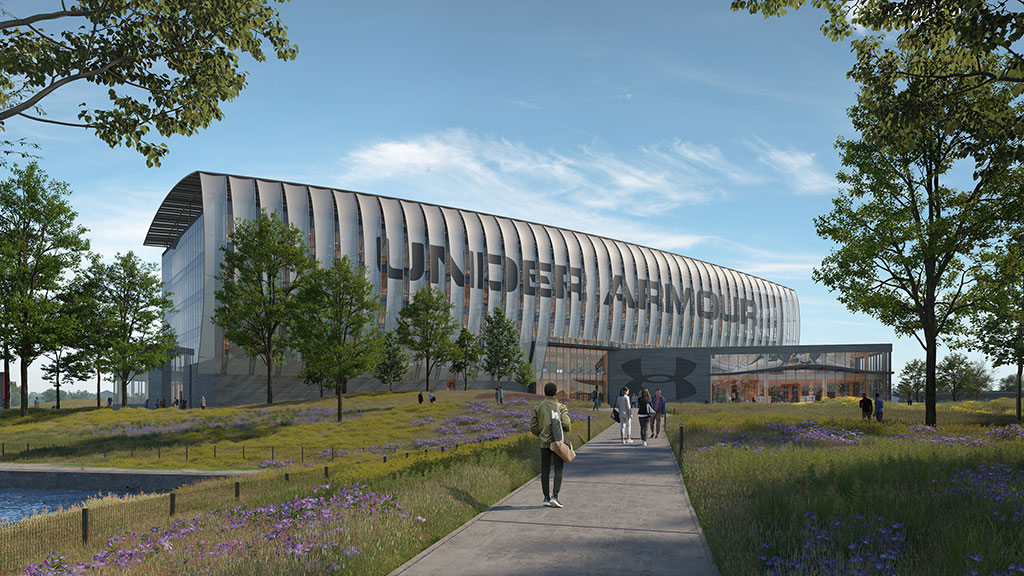

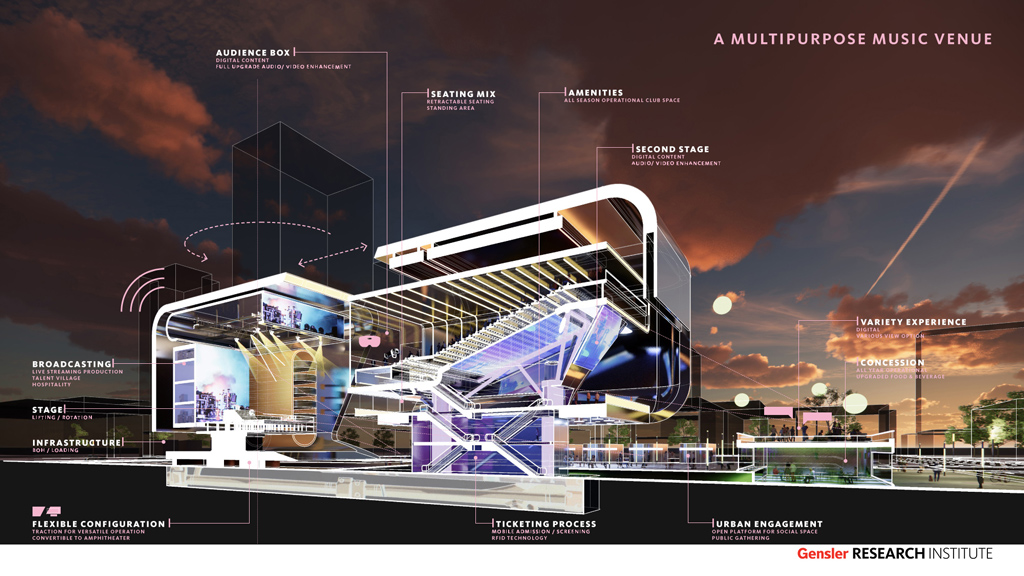

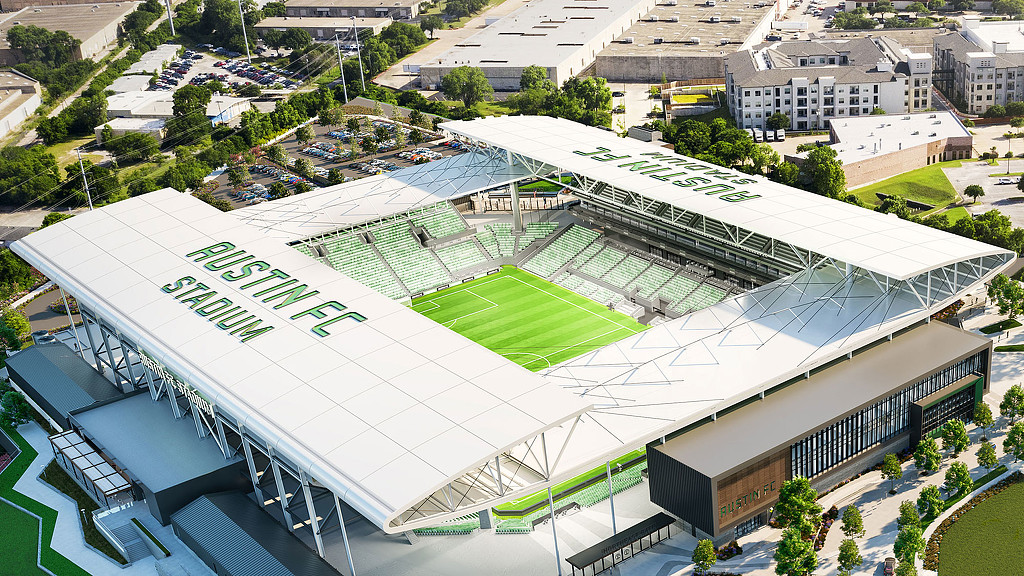

Trends to Watch Shaping the Future of Sports

Gensler’s Sports leaders explore the design trends redefining the next era of sports design, from fan-first districts to athlete-driven spaces.

December 09, 2025

|

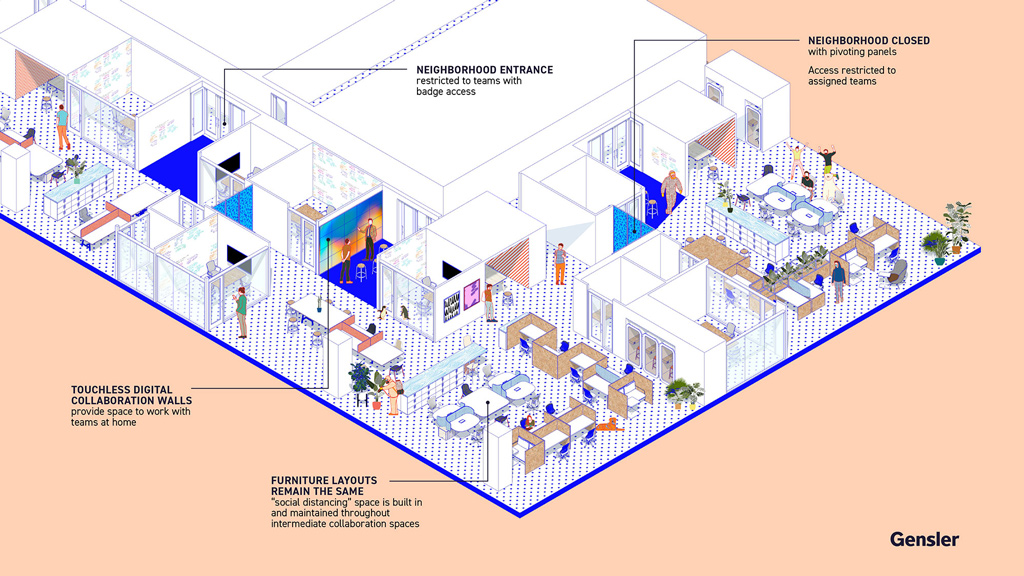

10 Workplace Trends for 2026: What’s In and What’s Out?

This is the year of bold moves, human-first thinking, and AI that doesn’t just answer questions but joins the team.

December 05, 2025

|

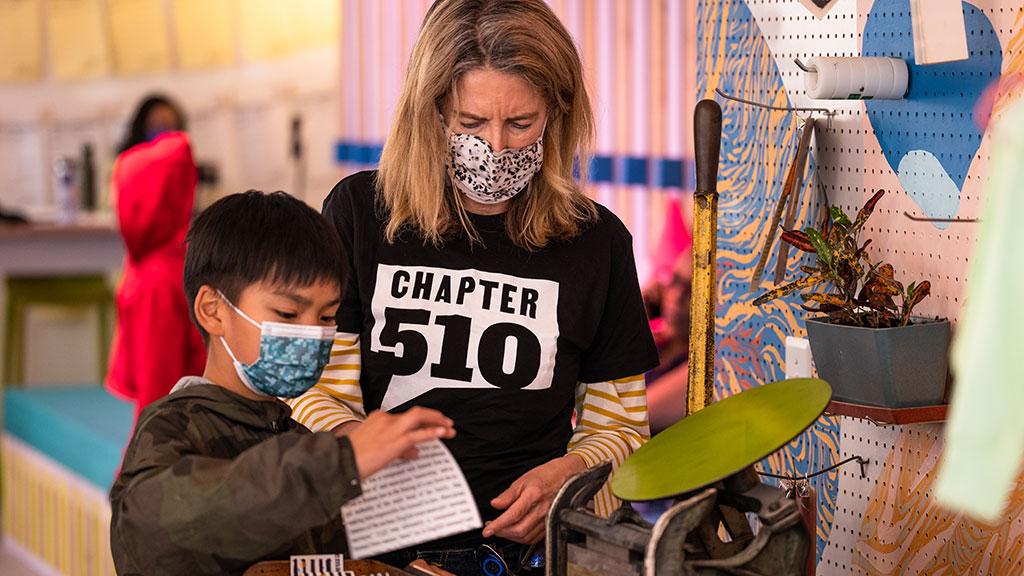

How Design Can Advance Diverse Nonprofit Missions

Nonprofits can use architecture and design strategies in campus development to amplify their mission impact and operational excellence

December 03, 2025

|

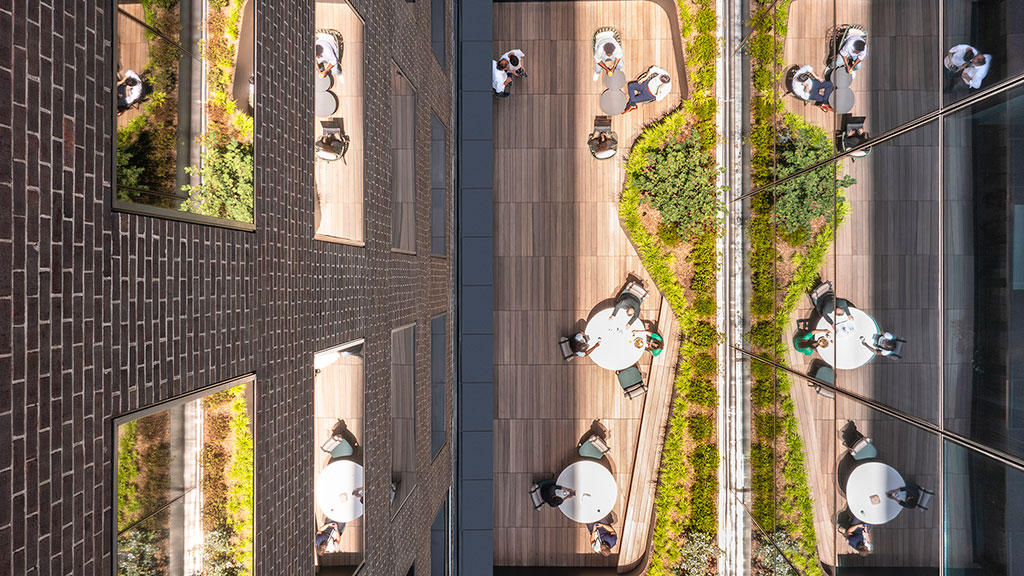

How Nokia’s New R&D Campus Raises the Bar for Canada’s Tech Ecosystem

The company’s new space in Ottawa replaces the traditional workplace model with one centered on employee experience.

December 02, 2025

|

Trends to Watch: How Global Events Build Magnetic Place Brands

From the Super Bowl to the FIFA World Cup, marquee events transform urban environments into platforms that amplify civic pride and create lasting impact.

November 24, 2025

|

Transforming Pier 94: A Collaborative Journey in Sustainable Design and Adaptive Reuse

Pier 94 on Manhattan’s Hudson River waterfront will soon be home to New York City’s first purpose-built, state-of-the-art film and television production facility: Sunset Pier 94 Studios.

November 21, 2025

|

Designing the Future of Travel at Pittsburgh International Airport

Building a terminal rooted in flexibility, passenger experience, and the spirit of a city that’s reinventing itself.

November 19, 2025

|

NEXT NEXT: Redefining Science Work for the AI and Machine Era

Our new concept looks at how AI and automation are redefining the science workplace and reshaping the future of labs.

November 18, 2025

|

Test, Don’t Guess: A New Approach for Healthcare Design

Healthcare leaders are modeling multiple futures before breaking ground — shifting from fixed bets to flexible strategies.

November 14, 2025

|

Inside Bangalore’s Talent Race: The Power of Purposeful Workplace Design

While Bangalore continues to face real challenges, such as aging infrastructure, relentless traffic, and a growing water crisis, the city is emerging as a strategic hub for global workplace expansion and a magnet for newcomers.

November 14, 2025

|

The New Job for the Airport CEO: It’s More Challenging — and More Uplifting — Than Ever

In this pivotal moment, we have an opportunity to design airports and terminals that feel less like infrastructure and more like inspirational destinations.

November 12, 2025

|

Designing Tomorrow’s Shopping Centers: Global Ideas From Kuwait, Costa Rica, and Beyond

Around the world, developers are experimenting with new models that expand the meaning of “retail.” For U.S. retail designers, these examples offer valuable lessons for an era defined by shifting consumer behavior, climate pressures, and the need to create authentic community experiences.

November 12, 2025

|

Beyond the Screen: Making Digital Beauty Brands Shine in Real Life

How digital-first retailers can navigate the crucial transition of a brand into physical space.

November 12, 2025

|

Reinventing the Strip: How to Make Everyday Retail Irresistible

What makes a strip mall “successful”? Discover the formula for staying local, lively, and loved.

November 12, 2025

|

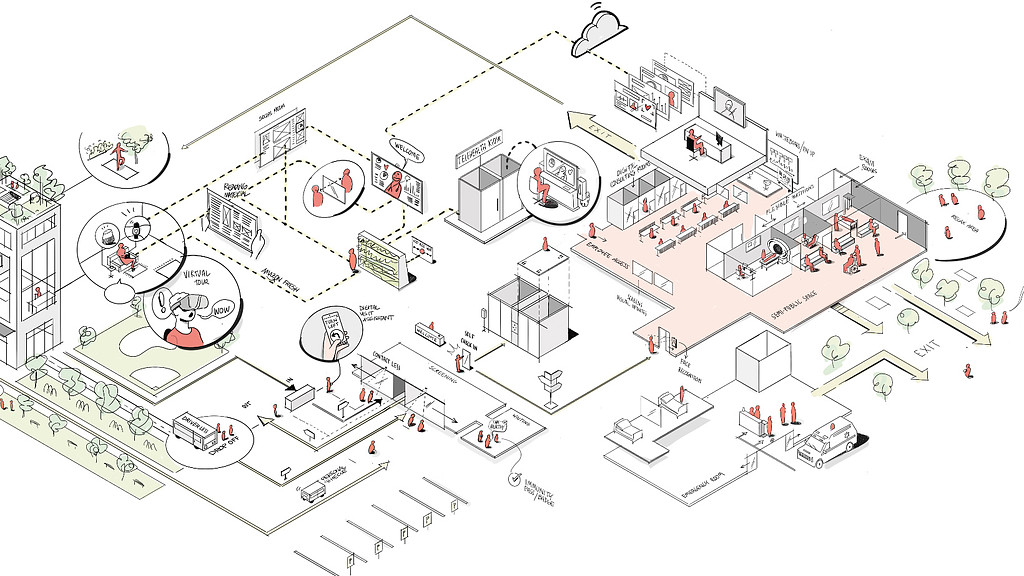

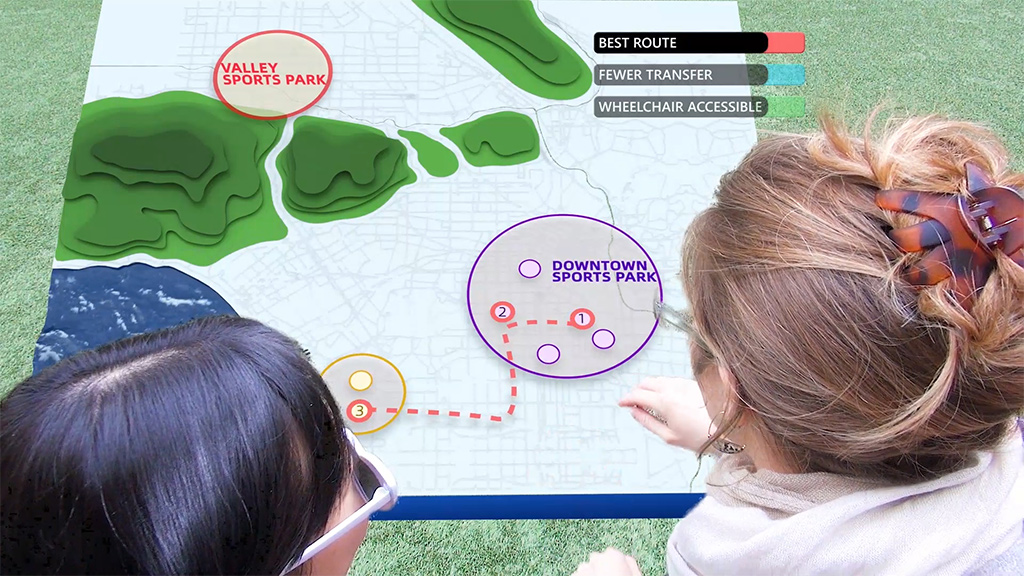

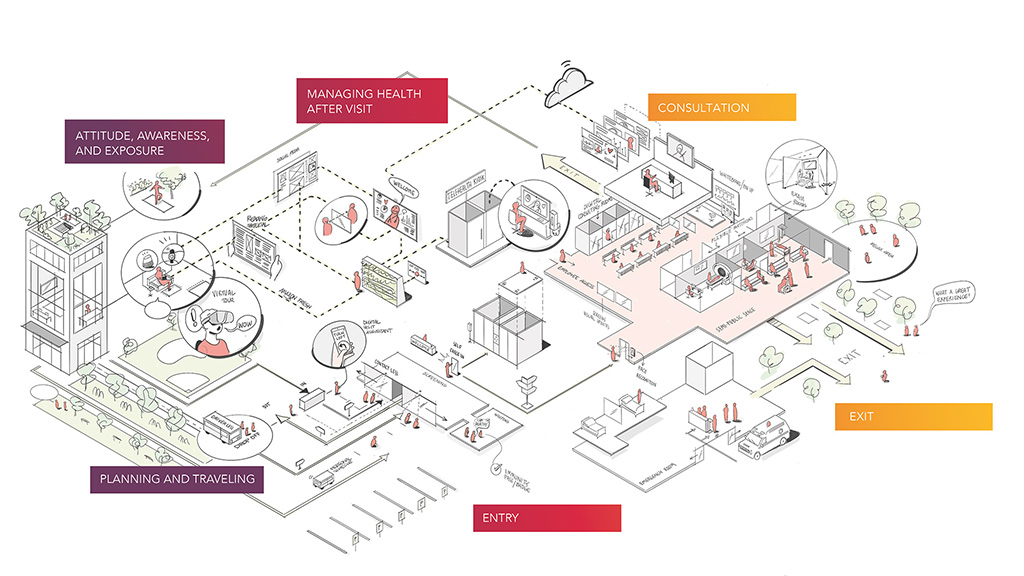

How Journey Mapping Shapes Design Opportunities for the User

Journey mapping is more than a tool. It helps teams visualize how users move through systems, spaces, and services over time, capturing not just what users do, but how they feel, what they expect, and where they encounter friction or delight.

November 12, 2025

|

More Than Just a Seat: The Lounge as the New Travel Destination

The new airport lounge is less about claiming a seat and more about creating a collection of experiences.

November 04, 2025

|

A New Hybrid Hotel Blends Japanese Culture and Texas Charm

The Miyako Hybrid hotel rethinks hospitality through a Texas-Japanese fusion hotel experience.

October 27, 2025

|

The New Economics of Sports Venue Design

From NIL-driven college athletics to multi-tiered VIP lounges and mixed-use districts, sports venues are evolving into dynamic business ecosystems.

October 22, 2025

|

How a New Vision for Flexible Co-Living Conversions Can Support Housing Affordability

Gensler and The Pew Charitable Trusts studied building typologies in 10 cities to better understand the potential in this unique office-to-residential conversion model.

October 21, 2025

|

San Francisco’s AI Boom Is Our Chance to Build a People-First City

The AI gold rush presents a rare opportunity to reinvest in our urban core, reconnect our neighborhoods, and rebuild our streets.

October 14, 2025

|

Age-Welcoming Cities: Designing for an Era of Longevity

The challenge of a rapidly aging population also presents an opportunity: to reimagine how we plan our cities.

October 14, 2025

|

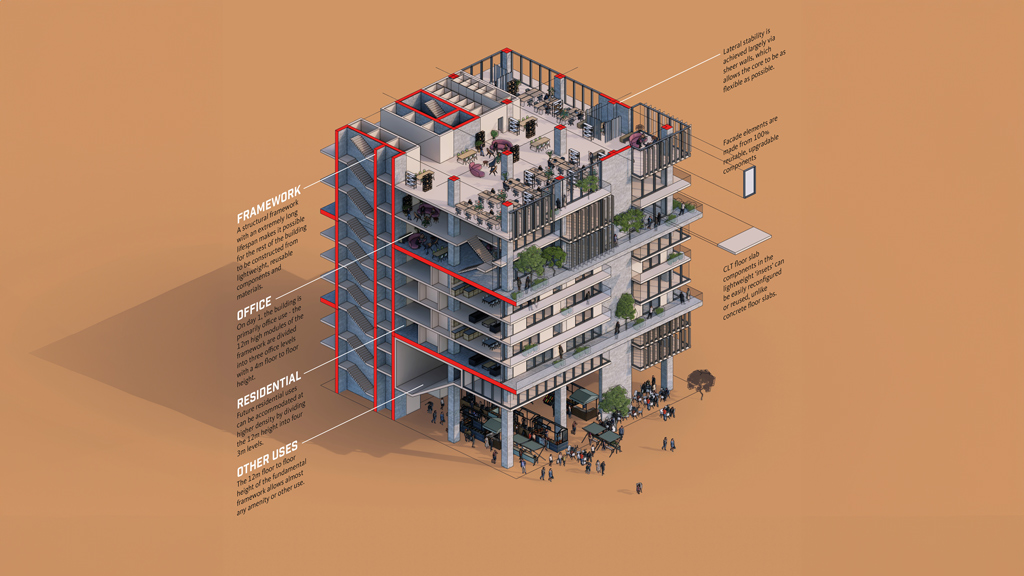

Mixed-Use Developments: A Sustainable Blueprint for Urban Growth

High-density mixed-use developments can be a powerful engine for economic growth, resilience, and cultural and socioeconomic cohesion.

October 14, 2025

|

A Multigenerational Workforce Demands Multigenerational Design

Employees over 65 are defying stereotypes and redefining expectations. Organizations that design with them in mind won’t just gain an edge today — they’ll shape the future of work.

October 08, 2025

|

The Future of Real Estate Metrics: Human Connection

The places that thrive in the years ahead will be designed to build relationships, inspire belonging, and foster togetherness.

October 07, 2025

|

Birmingham Living: The Next Chapter

This Q&A with Gensler residential leaders John Badman (London) and Jamie Rodgers (Birmingham) explores how Birmingham’s evolving housing market is shaping the city’s next chapter.

October 06, 2025

|

Where Champions Train

For the WNBA’s Phoenix Mercury and the Las Vegas Aces, world-class training and practice facilities helped propel them to the top of their game — and the league.

October 03, 2025

|

How Aviation Is Evolving for the Leisure Traveler

Airports are in the midst of a profound transformation. Confronted with aging infrastructure, rapidly advancing technology, and an unprecedented surge in leisure travel, these once utilitarian spaces are being reimagined as destinations in their own right.

October 01, 2025

|

Reimagining San Diego International Airport’s T1 as a Global Gateway

A bright, new modern terminal and roadways transform the travel experience.

October 01, 2025

|

Designing a 24/7 Entertainment Hub in Reno

The Grand Sierra Resort Reno Arena is more than a sports venue; it’s a fully integrated destination built around seamless entertainment.

September 30, 2025

|

Designing German Cities and Workplaces for a Thriving Economy

Gensler Germany’s leaders explore how urban design, workplace innovation, and strategic investment in public and private spaces can strengthen German cities.

September 29, 2025

|

Scaling Circular Design: Key Policies, Standards, and Strategies

As momentum grows for circular design, cities and clients face significant challenges and opportunities to implement it widely.

September 24, 2025

|

Climate Change Is Threatening What We Love About Cities

If cities hope to thrive in the face of climate change, they’ll need to balance emotional connection with environmental resilience.

September 23, 2025

|

The Carbon Impact of a Workday

When people calculate their carbon impact, they typically consider their cars, food, clothes, and flights. But they rarely consider where they spend their day. It’s time to change that.

September 22, 2025

|

Designing a New Way to Think in the Age of AI

Gensler co-CEO Jordan Goldstein speaks with Kristen Conry, Senior Vice President of Global Design, Marriott, about how AI is blending creativity with operations, storytelling with strategy, and vision with impact.

September 19, 2025

|

7 Myths Dogging Efforts to Fully Electrify Buildings — Let’s Bust Them

Despite misconceptions, building electrification is a practical and beneficial choice for many building owners.

September 19, 2025

|

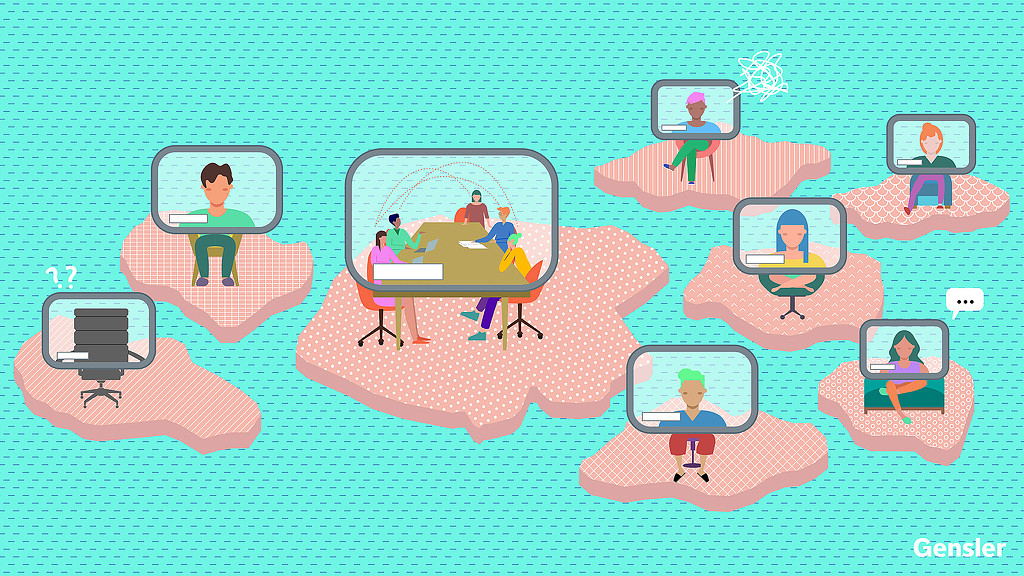

Human and ‘Digital Employee’ Collaboration Will Transform Workplace Design

AI integration will soon impact physical spaces, potentially reshaping individual and group culture within organizations.

September 17, 2025

|

Reimagining Haussmann: Adaptive Workplace Design in the Parisian Urban Fabric

A look at how we can adapt these historic apartments to become sustainable, flexible, and human-centered workplaces for the future.

September 17, 2025

|

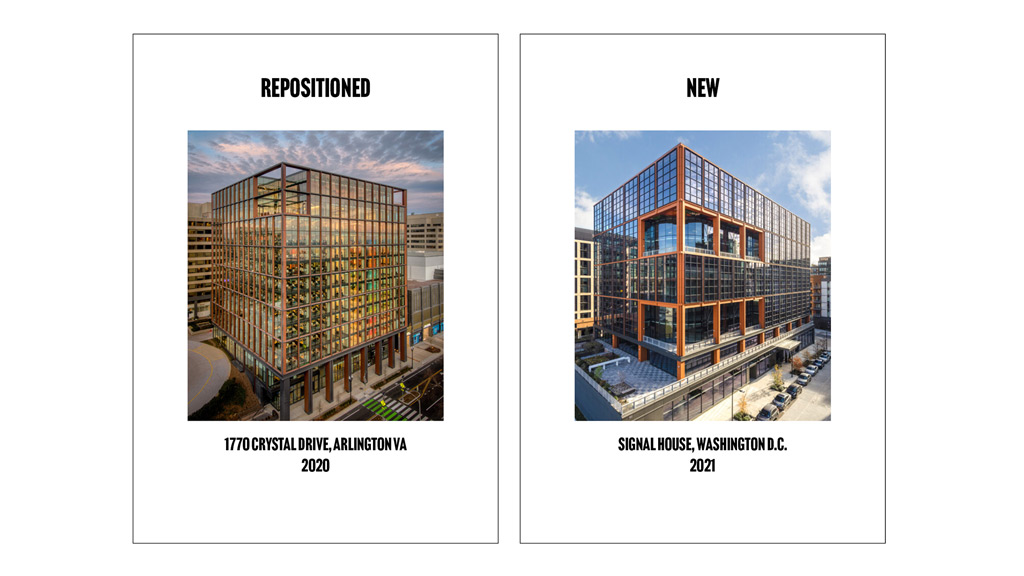

Retrofit at Scale: A New Blueprint for Investible Urban Development

A conversation with Gensler’s Harry Cliffe-Roberts and Opportunity London’s Jace Tyrrell on why retrofit is emerging as a preferred solution — and how this cross-industry guide is helping move the dial.

September 16, 2025

|

Design as Storytelling: How AI Is Transforming the Way We Imagine, Create, and Connect

AI isn’t here to replace creativity. It’s here to amplify it — helping us move from inspiration to iteration with greater speed and substance.

September 11, 2025

|

Energy Meets Art: How Museums Are Rethinking Climate Control

Energy-saving regulations and new techniques are prompting museums to reexamine how they manage indoor climate control.

September 11, 2025

|

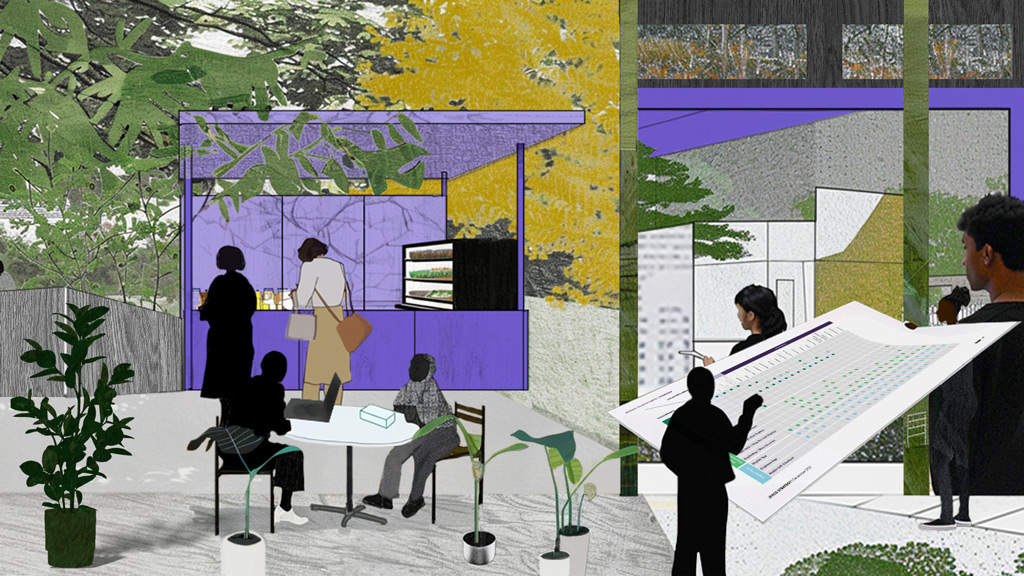

How San Francisco Can Apply Startup Culture to Unlock Housing Solutions

We explore four strategies to bring iterative, bold approaches to address the city’s housing shortage.

September 10, 2025

|

Why Japan’s Workplace Trends Are Moving Against the Global Current

How companies in Japan can adapt their workplace solutions to counteract the country’s stagnating office experience.

August 27, 2025

|

Six Decades of Creativity: Interior Design Magazine Celebrates Gensler’s 60th Anniversary

The industry publication marks a milestone in the firm’s history with a roundup of global projects and people shaping what’s next in design.

August 25, 2025

Why Modern Hiring Centers Matter in Today’s Competitive Job Market

With thoughtful, strategic design, a hiring center or interview suite can be a valuable asset to attract top talent.

August 22, 2025

|

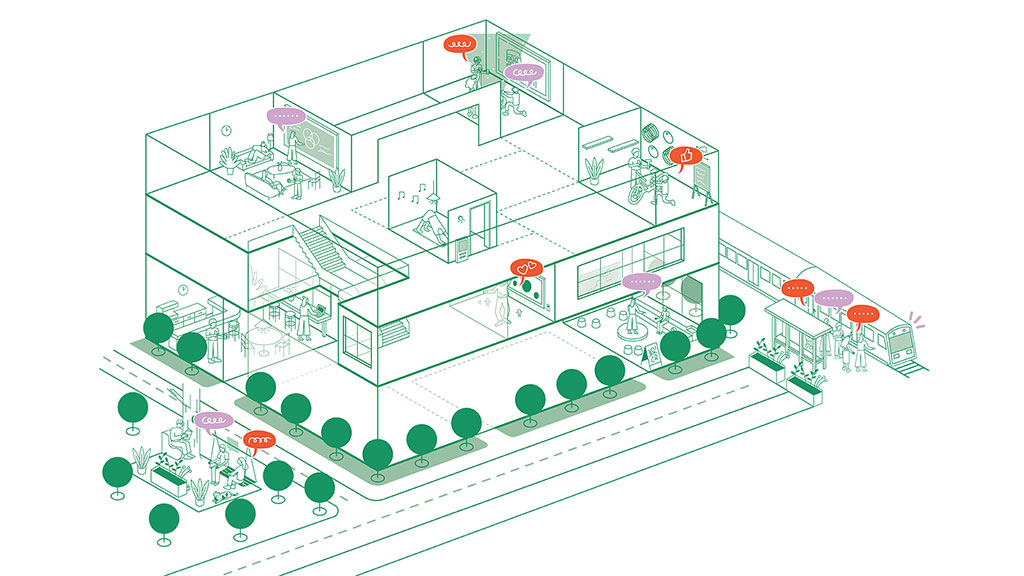

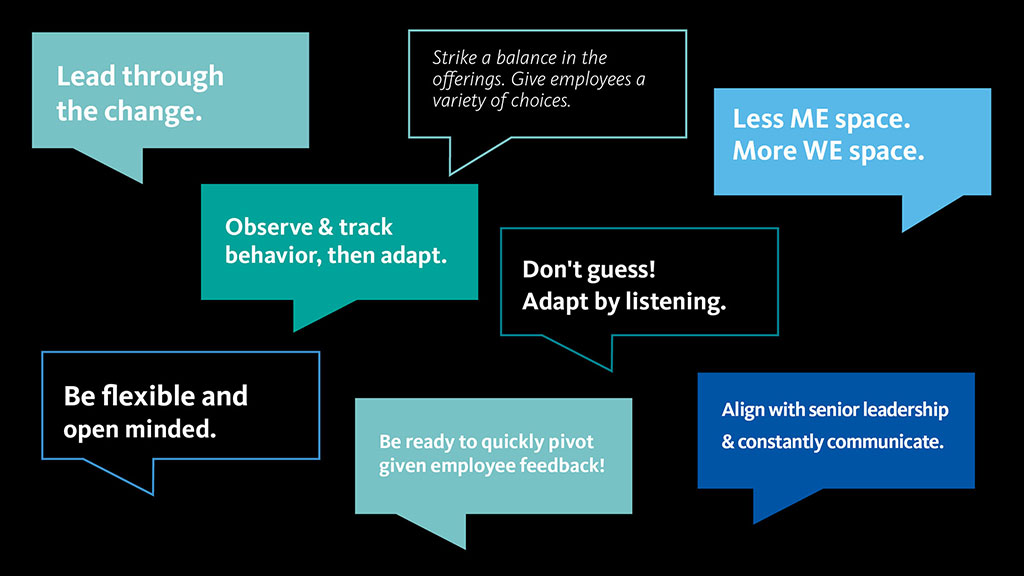

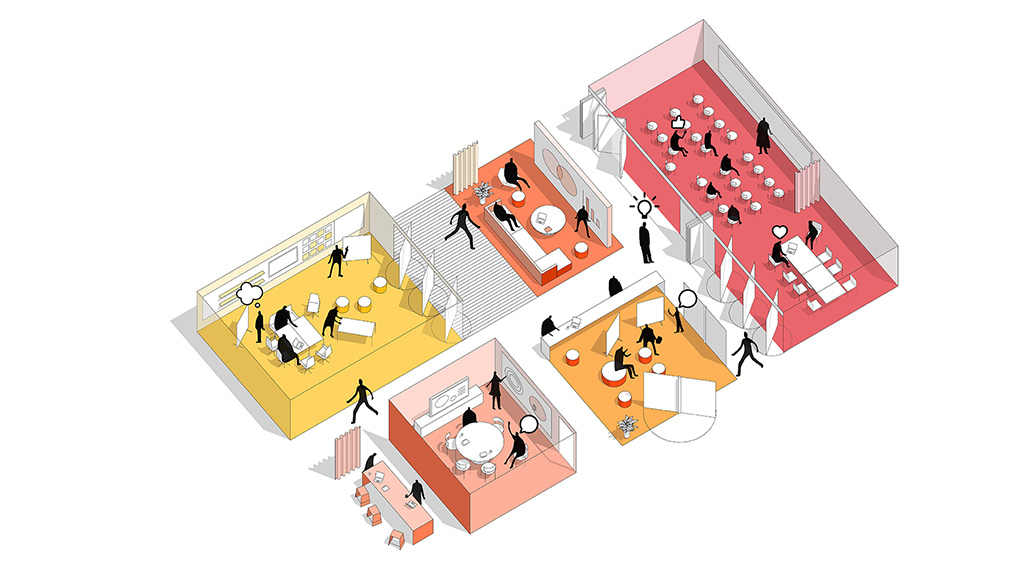

Designing Workplaces That Work — With Your People

When employees are involved in the planning and design process, the workspaces we create are more effective, engaging, and human.

August 21, 2025

|

Blueprint for Change: How Modern Training Centers Are Redefining the Trades

With thoughtful design, modern training centers for skilled trades are reshaping perceptions of vocational education.

August 18, 2025

|

How Business Schools Are Embracing Workforce Preparedness and Student Well-Being

To prepare students for success, campuses are becoming interdisciplinary, flexible environments that foster career readiness and holistic growth.

August 18, 2025

|

Trends to Watch Shaping the Future of Student Housing

In a time of great market uncertainty, student housing is proving to be a good investment for developers and revenue-positive for campuses.

August 13, 2025

|

Designing Campus Spaces for Tomorrow’s Workers in the Age of AI

Higher education institutions that embed human-plus-technical skills into an ecosystem of third spaces will help prepare tomorrow’s workforce.

August 12, 2025

|

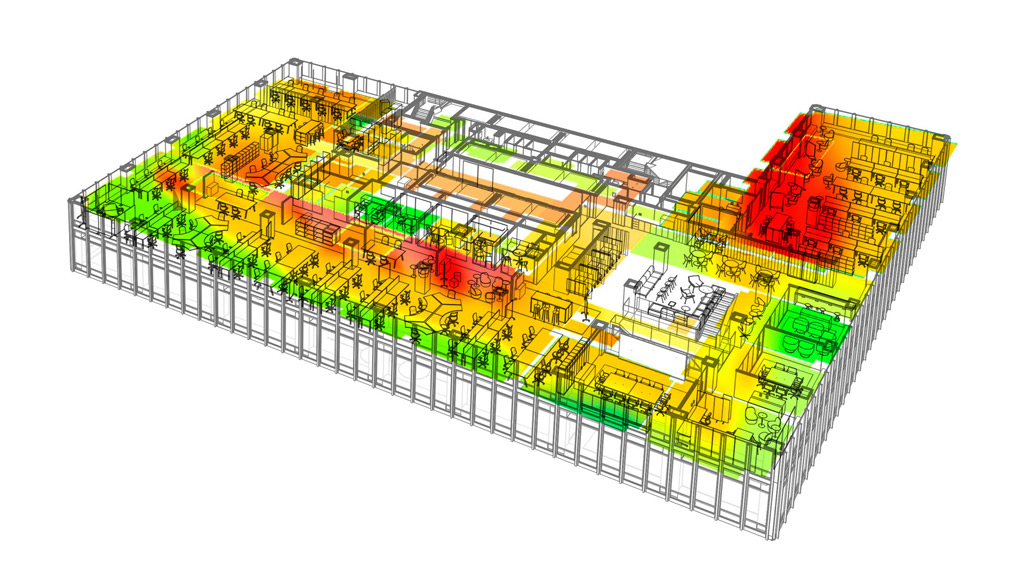

Leveraging Predictive Analytics to Navigate Uncertainty in Campus Workplaces

Predictive analytics is rewriting traditional campus planning rules, allowing institutions to design spaces that expand and contract with actual demand patterns.

August 12, 2025

|

Families Are Leaving Cities — Here’s How to Win Them Back

Children are critical to well-functioning cities. How can we ensure our cities work well for children and encourage parents to stay?

August 06, 2025

|

Designing for the Next Generation of Business Leaders

By investing in an experience-rich building, Purdue University’s Mitch Daniels School of Business aims to grow the next generation of business leaders and entrepreneurs.

August 01, 2025

|

How Strategic Shifts Can Reignite Employee Engagement

In today’s workplace, employee engagement isn’t just a buzzword — it’s a vital force behind organizational success.

July 30, 2025

|

Unlocking Value in Class A High-Rises: The Strategic Advantage of Spec Suites

In Class A commercial towers, spec suites are becoming a go-to strategy for converting vacancy into value.

July 30, 2025

|

Doing More With Less: Designing Small Spaces for Big Impact

Right-sized workplaces are redefining what it means to be effective — and proving that good design is measured not in square footage, but in experience.

July 28, 2025

|

3 Overlooked Human Factors That Make-or-Break Mergers and Acquisitions

Organizations that integrate people, culture, and physical space into their M&A strategy can unlock lasting value.

July 25, 2025

|

Reenvisioning Retail Centres: Lessons From China for the Middle East

We explore how key lessons from China’s retail evolution can reshape the future of retail centres in the Middle East.

July 23, 2025

|

Unlocking the Power of Forgotten Space to Combat Loneliness

By embracing the potential of empty space, reimagining in-between spaces, and extending the life of cities beyond traditional hours, we can unlock new value and bring people together.

July 21, 2025

|

The Power of Clean Air in Sports-Centered Design

In arenas, training centers, and stadiums, air quality is not just a comfort factor — it’s a competitive edge, affecting athletes’ ability to train, compete, and recover.

July 16, 2025

|

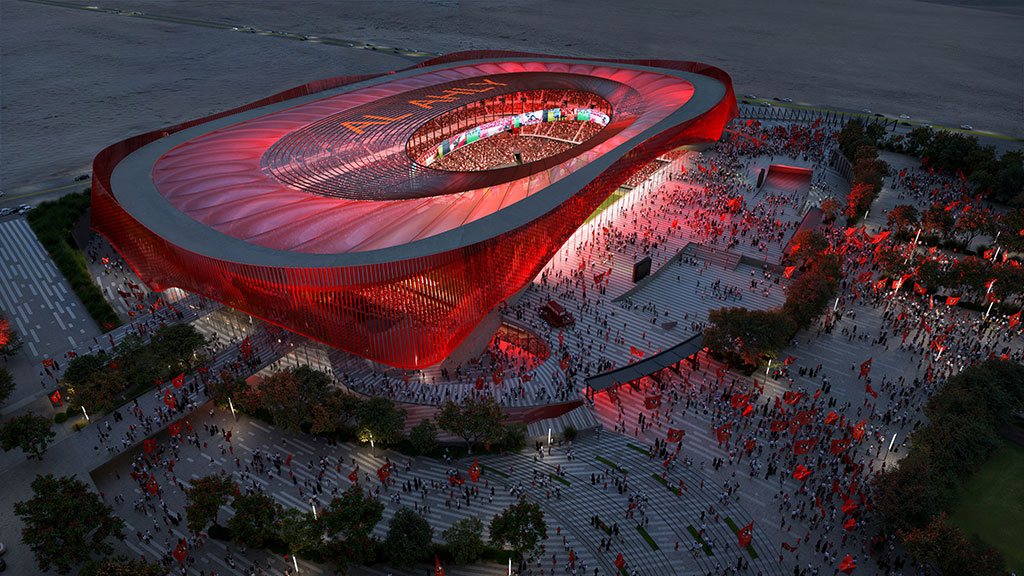

Al-Ahly Stadium Brings Fans Closer to the Action

Facing height and capacity restrictions, an innovative design solution turned these challenges into an opportunity to design a year-round, landmark sports venue.

July 10, 2025

|

Debunking 3 Myths About Generational Differences in the Workplace

As generational differences narrow, organizations should focus their workplace strategies across the entire talent spectrum.

July 09, 2025

|

The Evolving Role of Hotels in Retail-Driven Mixed-Use Environments

Hotels within mixed-use developments are becoming curated retail destinations and dynamic contributors to a vibrant urban experience.

July 07, 2025

|

The Rise of Outdoor Spaces at Airports

Major U.S. airports are actively incorporating outdoor terraces and patios as a passenger amenity — and transforming the traveler experience.

July 02, 2025

|

Airports Can’t Stop. Here’s How to Keep them Functional During Construction.

We share fresh optimism about how to improve the airport construction process. It starts with travelers’ experience as they pass through an airport with ongoing construction.

July 02, 2025

|

5 ‘Out of the Box’ Strategies for the Retail Real Estate Market

As big box retail closures mount, here’s a look at five unique uses to repurpose large, vacant spaces in a changing landscape.

July 02, 2025

|

Trends to Watch Shaping the Future of Airports and Aviation

Gensler’s aviation leader discusses what’s next for the future of air travel and how airports can cater to a new type of leisure traveler.

July 01, 2025

|

Urban Air Mobility Is Here. Here’s How Cities Can Adapt.

Advanced air mobility is ready for launch. The next crucial step: preparing buildings and infrastructure to get this sustainable mobility solution off the ground.

July 01, 2025

|

What Airports Can Learn From Stadiums and Ballparks

Here are six lessons from sports venue design to create a more seamless passenger experience.

July 01, 2025

|

Designing ‘the Quiet Airport’ at SFO

San Francisco International Airport (SFO) is helping to ease the passenger experience through hospitality-driven, inclusive design.

June 30, 2025

|

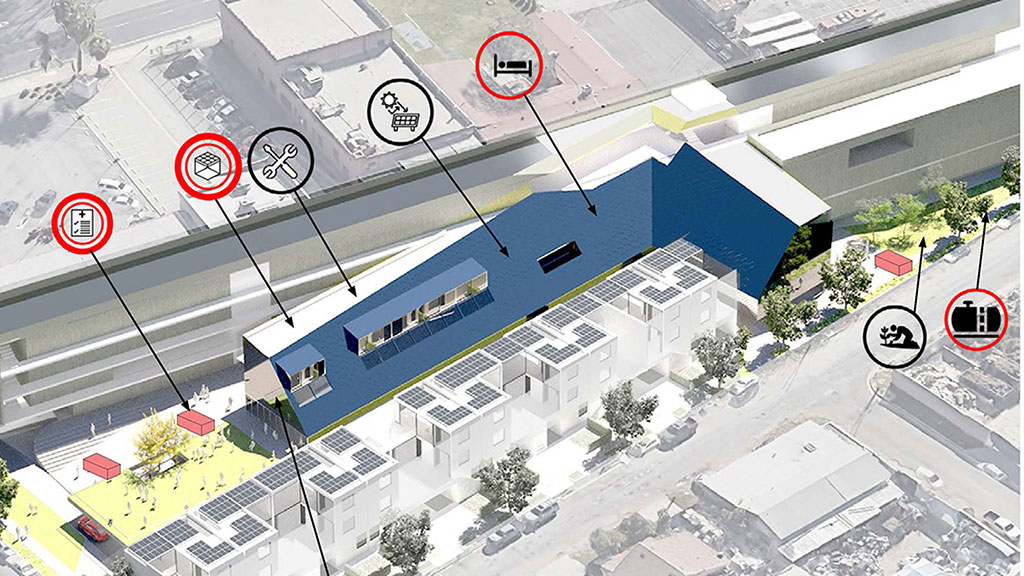

Building a New Temporary Home for Pali High

In the wake of L.A. wildfires, Gensler transformed a former Sears department store into a high school for 2,500 students in just four weeks.

June 25, 2025

|

How London’s Green Real Estate Can Lead the Global Climate Agenda

Despite global decarbonisation efforts, emissions continue to rise. But the UK is quietly and steadily reducing its carbon footprint.

June 20, 2025

|

Office-to-Hotel Conversions: Resilient Opportunities for Downtown Districts

Older and smaller Class B or C office buildings have been hit hard by high vacancy rates. Converting them to efficient, business travel hotels could offer an economical solution that supports the overall health of downtown business districts.

June 18, 2025

|

Belonging Begins at Home: Why Attainable Housing Is a Civic Imperative

We explore five strategies that demonstrate how design, policy, and planning can come together to build more inclusive, resilient communities.

June 17, 2025

|

The Top 10 Cities People Don’t Want to Leave

Gensler’s 2025 City Pulse survey reveals the top cities where people not only move to, but also stay long-term.

June 17, 2025

|

Historic Buildings: A New Solution for Modern Data Centers

Repurposing historic buildings into data centers is a compelling strategy for heritage preservation, sustainability, and digital transformation.

June 17, 2025

|

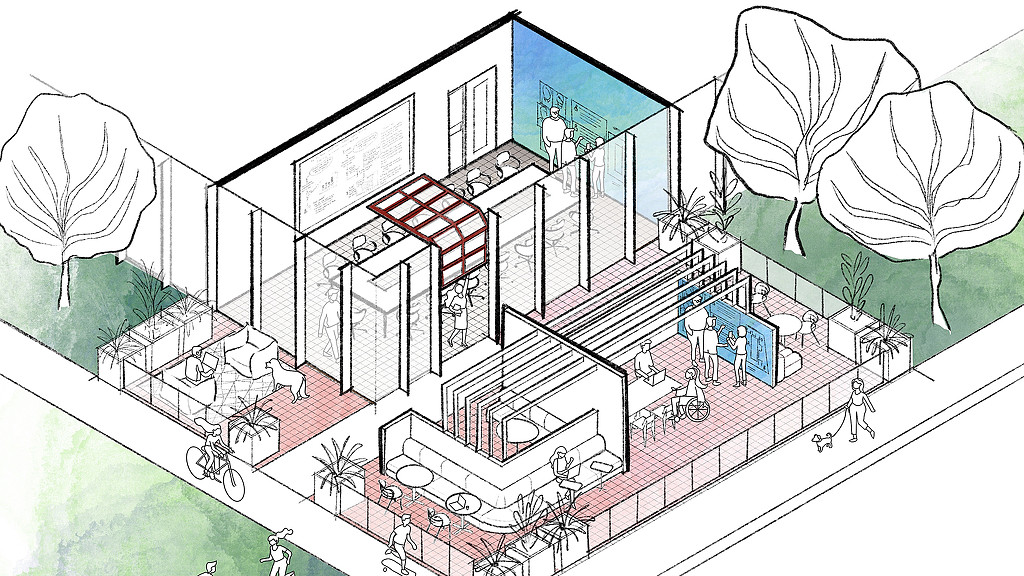

Reimagining Care in the Heart of Our Cities

An innovative intergenerational care concept seeks to transform how we support caregivers while revitalizing underutilized commercial spaces.

June 09, 2025

|

Libraries: The Last Urban Oasis

Libraries are no longer just a place for books; they play an integral role as the last bastion of democratic space in our cities.

June 06, 2025

|

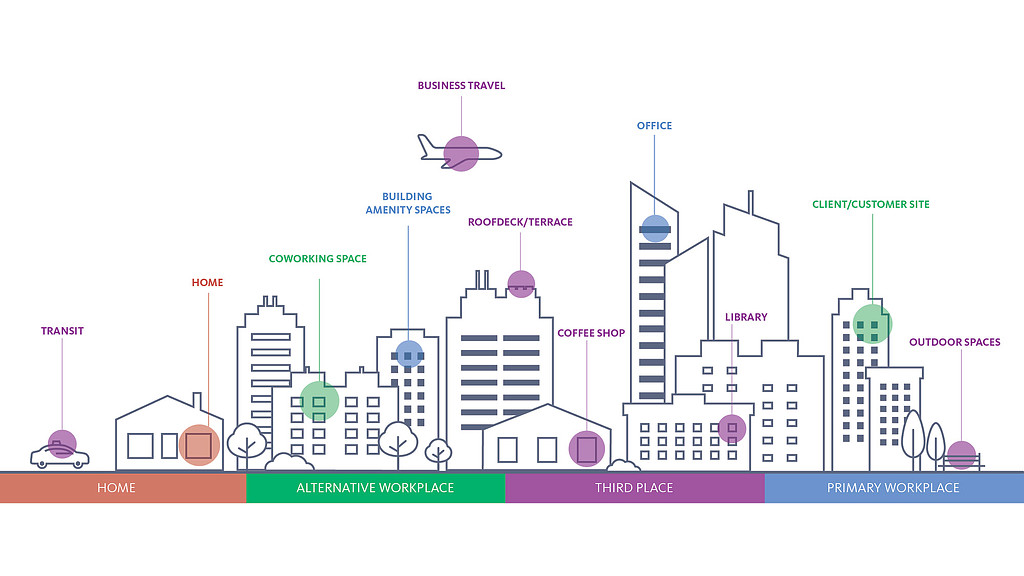

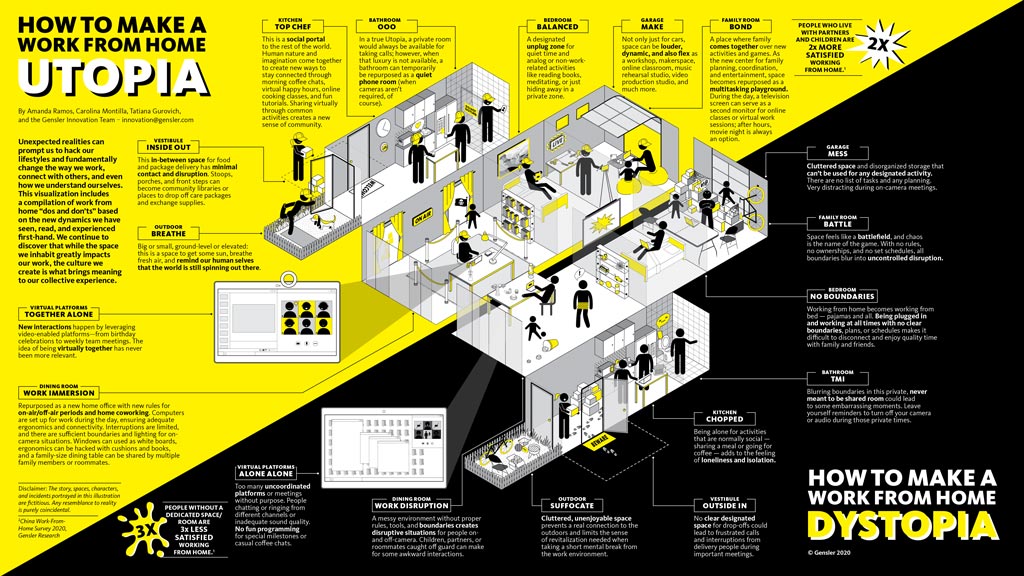

How the Future of Work Is Influencing Workplace Design

While workplace design changes incrementally, the past few years radically transformed our expectations of an office and how we can design for what’s possible.

June 06, 2025

|

How Cities Can Establish Resilient Communities

To mitigate potential damage and risk, cities can form resilient communities to proactively prepare for, respond to, and recover from a disaster.

June 04, 2025

|

The Future of Work Is Human: Designing for Culture and Experience

The challenge in front of us is to design places that empower creativity, build belonging, and support people and teams to do their best work — whatever that looks like.

June 03, 2025

|

How a Challenging Site Fuelled a Bold New Workplace

A new building at The Goodsyard will transform an untapped site into a dynamic destination in London.

June 02, 2025

|

How the Nighttime Economy Is Rewriting Urban Design

Cities around the world are beginning to take the nighttime economy seriously — not as a separate or secondary system, but as a vital counterpart to daytime urban life.

May 28, 2025

|

The 20 Cities Attracting the Most Newcomers

New city residents often leave within five years. To remain successful, these magnetic cities must also engage and retain their new populations.

May 28, 2025

|

A New Vision for Urban Design in Tropical Climates

Through thoughtful, climate-responsive design, seemingly adverse conditions can become a distinct advantage for tropical cities.

May 28, 2025

|

A Surprising Reason to Feel Good About Returning to the Office

Why shared office space is a greener choice than working from home.

May 22, 2025

|

What Draws People to Cities — and What Makes Them Stay?

Gensler’s City Pulse 2025 research offers insights into the factors attracting people to cities and compelling them to stay.

May 21, 2025

|

The New Club Workplace: More Than an Amenity

The next generation of tenants wants an experience-driven, unconventional shared amenity space, prompting landlords to rethink their offerings.

May 15, 2025

|

The New Workplace Experiences That People Crave

Employees want to move past the corporate workplace experience to more creative, natural, and residential environments.

May 15, 2025

|

Designing an Eco-Retreat in Costa Rica’s Rainforest

Gensler Paris’ Managing Director explores how hospitality trends influence the design of this new Costa Rican resort — from the demand for cultural immersion to the rising appeal of slow travel.

May 15, 2025

|

Latin American Malls: The New Town Square

Malls across Central and South America are layered, experience-rich destinations that bring people together.

May 14, 2025

|

It’s Time for the Traditional Conference Room to Make Way for New Spaces

It’s time to forgo the traditional conference room and make space for more intentional, adaptable environments that are aligned with how people connect today.

May 12, 2025

|

Birmingham’s Renaissance: The City of 100 Quarters

How the city’s next evolution is embracing both innovation and heritage to shape a vibrant future.

May 08, 2025

|

How Summer FOMO Is Shaping the Canadian Workplace

Our latest research offers some insights into why a desire for flexibility, variety, and seasonal adaptability is influencing the workplace in Canada.

May 08, 2025

|

The Value of Time in Retail Environments

Time is a precious commodity, and brands that understand its value and choreograph both fast and slow retail experiences will thrive.

May 07, 2025

|

How AI Is Driving Innovation in the European Data Centre Market

The scale of data centre demand is driving innovations in energy generation, grid infrastructure, and cooling technologies.

May 07, 2025

|

Fusion Center Models: The Future of 24/7 Banking Support Hubs

In an increasingly digital world, banks are turning to Fusion Centers to protect and respond to cybersecurity threats, financial fraud, and other concerns.

May 06, 2025

|

How the AI Gold Rush Is Influencing Data Center Design Trends

Gensler’s Critical Facilities leaders discuss how the AI boom is influencing the shape, speed, and operations of data center design.

May 06, 2025

|

Lifestyle Living Is Redefining the Home in the Age of Belonging

We’ve identified five major trends shaping the future of living environments.

May 01, 2025

|

How Two Innovative Shelters Reimagine Refuge for the Homeless in Chicago

By prioritizing privacy and dignity, trauma-informed design can provide essential refuge and promote sustained healing.

April 30, 2025

|

How Law Firms in Mid-Tier Markets Are Leading Workplace Innovation

As law firms across the country reimagine the workplace, mid-tier markets are emerging as powerful leaders in this transformation.

April 29, 2025

|

Agency Is the New Workplace Amenity

By designing enough of the right spaces within the workplace, employers can create environments where employees have agency to choose the best space for their needs.

April 28, 2025

|

The Convergence of Tech and the Financial Workplace

The financial workplace is taking cues from the tech industry, shifting from one-size-fits-most to always-in-beta mode.

April 28, 2025

|

10 Opportunities for a More Resilient and Equitable Jersey City

Listening to the local community to improve climate justice, health, safety, and equity.

April 28, 2025

|

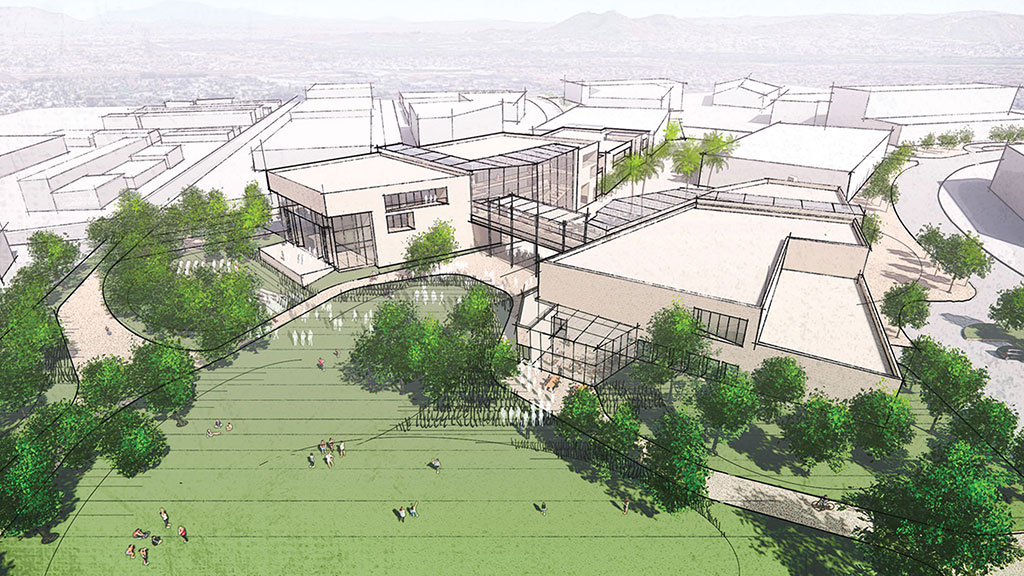

How Strategic Partnerships Are Shaping Academic Campus Development

Facing respective challenges, institutional-private sector collaborations can offer mutually beneficial opportunities for universities to expand their reach, optimize real estate, and enhance campus vitality, while providing developers with stable, high-value investment options.

April 25, 2025

|

Unlocking the Missing Middle: Why the U.S. Housing Model Needs a Redesign

How zoning, building codes, and financing reforms can unlock affordable, well-designed housing.

April 24, 2025

|

Why Now Is the Time for a Workplace Reset

To keep pace with changing workforce expectations, we need to think differently about the workplace.

April 24, 2025

|

Survivalist Architecture: The Age of Adapt & Reuse

Architecture must move beyond pure aesthetics to embrace solutions that prioritise environmental and social responsibility.

April 23, 2025

|

How to Design for Resilience

Resilient design is no longer a nice to have; it’s good business. Gensler’s Resilience Design report uncovers some key resilient design strategies.

April 22, 2025

|

Imagining a New Era for New Jersey’s Historic Art Factory

Originally built in the 1840s, the Art Factory is prime for a revitalization that preserves its character while serving the needs of a modern-day city.

April 16, 2025

|

The 18-Hour Campus: Strategies for Creating Vibrant, Round-the-Clock Hubs

Here are three strategies universities are adopting to create environments where students, faculty, and communities engage throughout the day and night.

April 14, 2025

|

How Design Drives Innovation in Education & Science

Gensler’s European Education & Sciences leaders explore how design can accelerate progress in these converging fields.

April 11, 2025

|

Urban Design’s Renaissance: How San Francisco Is Leading the Way

Cities everywhere are rethinking not just how they look and function, but how they can better serve the people who live in them. Few cities are as poised to lead this transformation as San Francisco.

April 09, 2025

|

5 Ways Suburban Office Campuses Are Transforming Into Thriving Communities

Tomorrow’s office campuses demand much more than a park and a café to attract and retain talent.

April 07, 2025

|

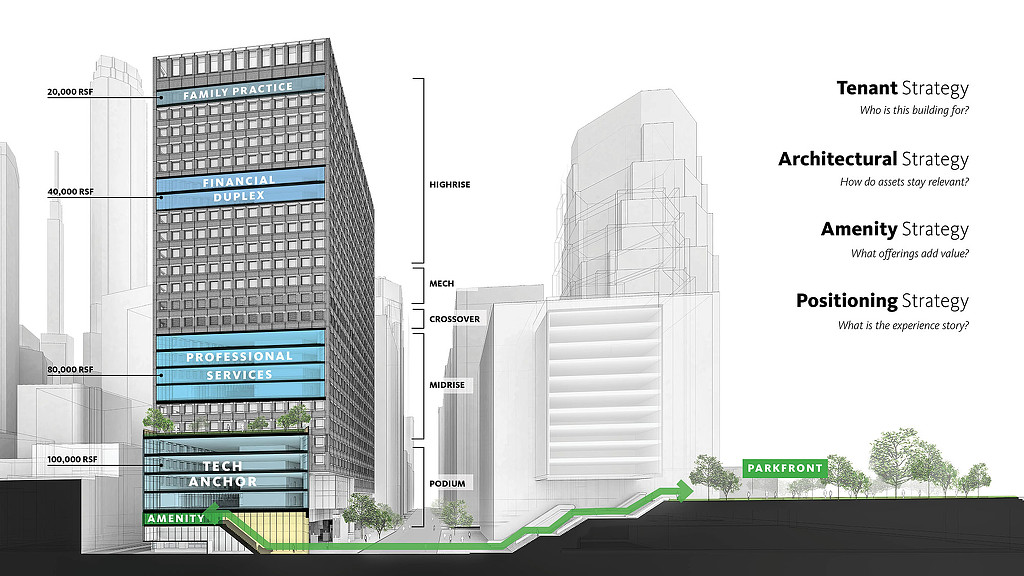

The Building as Brand: A Watershed Opportunity in Manhattan Office

As the city’s commercial real estate market undergoes unprecedented transformation, office space must be seen not as a commodity, but as a strategic investment with the potential to drive competitive advantage.

April 02, 2025

|

The Biggest Challenge to Office Conversions Isn’t Design — It’s the Status Quo

Office-to-residential conversions have the ability to unlock affordable housing and revitalize cities, but only if the market can move beyond the status quo.

April 01, 2025

|

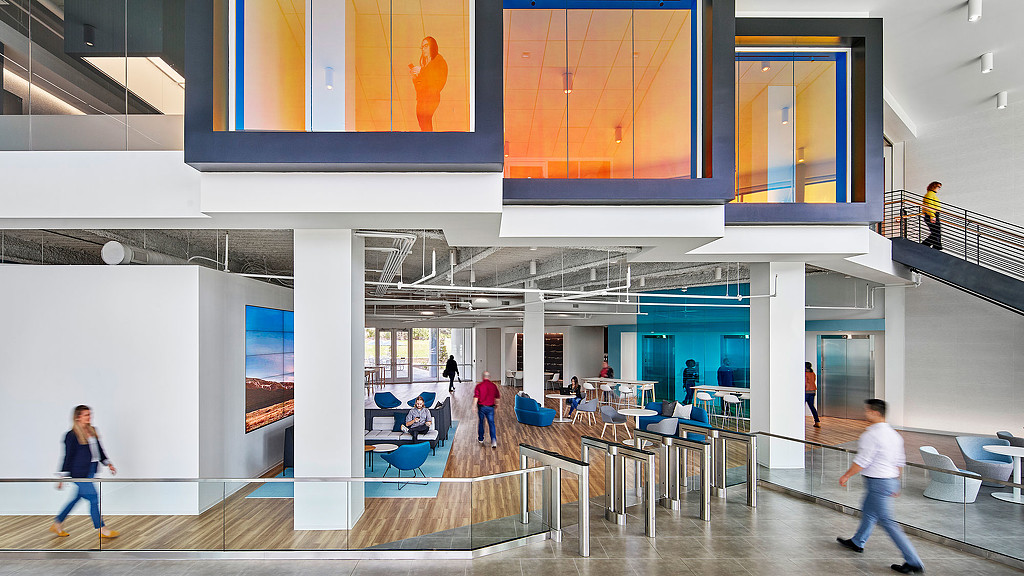

Bandwidth Headquarters: A Workplace Designed Not Just for Work, But Life

An amenity-forward design approach cultivates a vibrant and dynamic workplace environment, empowering every employee to perform at their peak potential every day.

April 01, 2025

|

Live Event Amenities: The Next Frontier for Creative Workplaces

Companies are investing in live event-ready amenity spaces to attract talent, fuel creative work, and create buzz in the workplace.

March 31, 2025

|

What’s Next for the Workplaces of San Francisco?

As the city’s office market navigates recovery, landlords, building owners, and employers must consider the varying needs of future real estate vs. the status quo.

March 28, 2025

|

Why Now Is the Time to Double Down on the Promise of California Community Colleges

How these essential institutions could drive local, inclusive economic recovery.

March 26, 2025

|

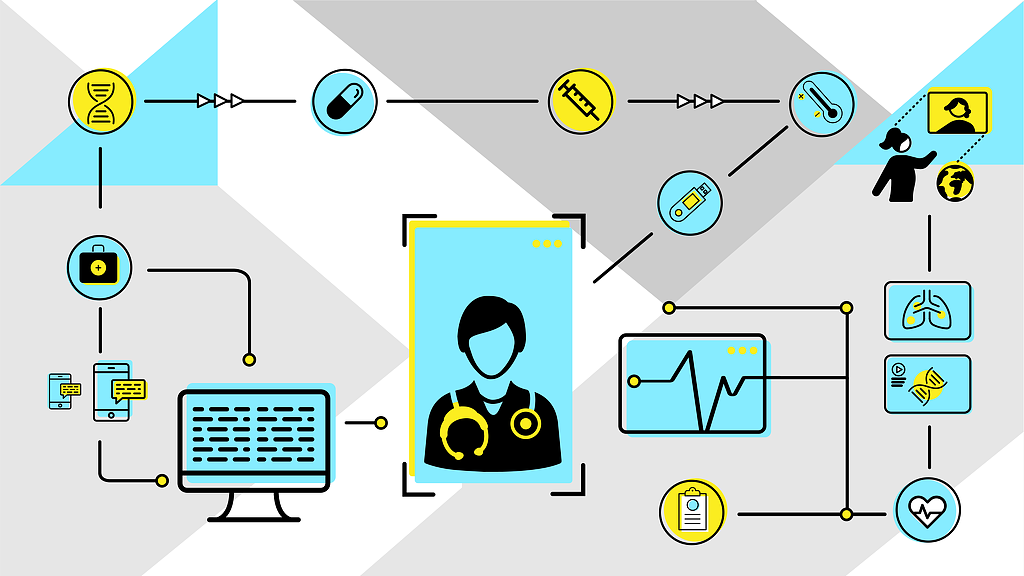

How the Rise in Digital and Home Health Will Transform Healthcare

New technologies and digital tools leveraging AI are starting to redefine how we manage our personal healthcare needs — and it starts at home.

March 25, 2025

|

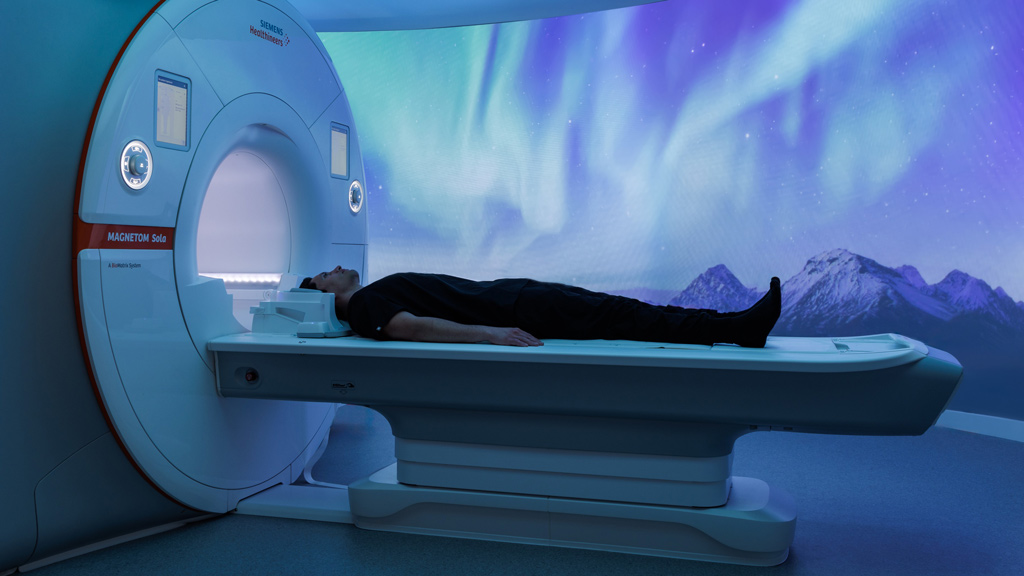

Realizing the Value of Artificial Intelligence When Planning Tomorrow’s Healthcare Facilities

The true value of AI lies not just in its ability to revolutionize devices and treatments but in its power to drive ROI through smarter, more adaptable healthcare environments.

March 24, 2025

|

Right-Sizing the Community Hospital: Optimizing for the Future

As U.S. health systems prepare for an uncertain future, our prototype hospital looks to expand care with fewer beds.

March 24, 2025

|

Trends to Watch Shaping the Future of Wellness

Gensler’s Wellness leaders discuss the opportunities shaping the future of wellness, from wellness real estate to inclusive design.

March 19, 2025

|

Reimagining Downtown: Transforming Underused Civic Buildings for a Vibrant Future

Former courthouses, grand banks, and other historic buildings at the center of our cities offer great potential to attract the public and activate our civic spaces.

March 17, 2025

|

Designing a New Future of Cities Through Wellness and Experience Design

How cities can take an active role in fostering healthier, more fulfilling urban lives for residents and visitors.

March 14, 2025

|

Creating a More Resilient Future With Green and Thriving Cities

As the demand for sustainable and liveable cities grows, urban planners and architects are adopting innovative strategies to harmonise built and natural environments.

March 13, 2025

|

Why Low-Carbon, Healthy Materials Are an Imperative for the Building Industry

Gensler’s updated Product Sustainability Standards™ aim to reduce the environmental impact of the building material supply chain, while driving industry change.

March 13, 2025

|

How Gensler’s Product Sustainability Standards™ Are Making an Impact in the Industry

We created the Gensler Product Sustainability Standards™ because we believe this is one of our most substantial opportunities for accelerating industrywide impact.

March 13, 2025

|

Introducing the Gensler Product Sustainability Standards™

We’ve set a new standard for all our projects to help increase demand for more regenerative materials in the building industry.

March 13, 2025

|

The Next Big Generation at Work May Not Be Who You Think

Historically, the fastest growing age group in the U.S. workforce has always been the upcoming generation. But not anymore.

March 12, 2025

|

Design Guidelines: The Most Powerful Tool in Your Real Estate Toolkit

Understanding a valuable tool that organizations can deploy to facilitate change in their real estate portfolio.

March 12, 2025

|

Healthier Spaces: Removing Harmful Chemicals From the Built Environment

Now is the time to take radical action and remove chemicals of concern from our buildings and spaces.

March 11, 2025

|

Three Principles for High-Impact Sustainable Design Guidelines

Translating sustainability commitments to design strategy.

March 10, 2025

|

Is Belonging the New Currency for Workplace Design?

By prioritizing belonging, we can create more impactful and transformative spaces that mitigate loneliness, foster connection, and drive value for people and organizations.

March 07, 2025

|

Designing for Flexibility in Senior Community Amenities

New insights in programming activities for tomorrow’s seniors will lead to the design of flexible, reconfigurable spaces and increased engagement.

March 06, 2025

|

How Branded Healthcare Environments Can Build Trust and Community

Brand identity plays a vital role in shaping patient experiences and reinforcing confidence in healthcare interiors.

March 03, 2025

|

Trends to Watch Shaping the Future of Senior Living Design

Gensler’s regional Northwest Senior Living leader discusses new housing models, amenities, and other opportunities shaping the future of senior living design

February 28, 2025

|

Why Resilience Planning Is Crucial to Safeguard Health Systems

Investing in proactive resilience planning, rather than reacting to weather and climate disasters as they unfold, will ensure uninterrupted, quality care.

February 27, 2025

|

Biodiversity as the New Frontier for Achieving Resilience in Real Estate

The biodiversity crisis is a fundamental challenge that impacts life, the global economy, and the real estate industry.

February 25, 2025

|

The Future of Mixed-Use Communities in Phoenix

Phoenix is well positioned for continued expansion, capitalizing on new technologies, sustainable practices, and architectural innovation.

February 20, 2025

|

Repopulating the Workplace: Why Collaboration Space Is in Danger

Despite their value, collaboration spaces are often the first to go when companies are looking for ways to repopulate the workplace.

February 18, 2025

|

The New Experiential Hybrid

The New Hybrid experience brings together the robust attributes of commerce, culture, and leisure, and recalibrates the urban experience.

February 11, 2025

|

The Uncertainty of Electric Power: A View from Houston

Through innovative design, regulatory support, and community participation, we can enhance our resilience to extreme weather events and ensure a more stable energy supply.

February 07, 2025

|

The Future of Lab Automation: Opportunities, Challenges, and Sustainable Design Solutions

Automation in labs isn’t just about advanced tools; it’s about creating an ecosystem that considers workflow efficiency, spatial design, and environmental sustainability.

February 07, 2025

|

How Repositioning Houston’s Astrodome Can Serve as a Model for Aging Sports and Entertainment Venues

A proposal to redevelop and repurpose the iconic stadium into a multi-use venue would preserve the building’s historic integrity while giving it new life.

January 31, 2025

|

What Do Consumers Want? Gensler’s U.S. Consumer Experience Report Uncovers Key Insights

Gensler’s latest consumer research delves into how design can impact human experiences for the better.

January 31, 2025

|

Communicating Sustainability: Quantifying, Qualifying, and Celebrating Climate Impact Achievements

Wherever a company or brand may be on its sustainability journey, telling the story of impact in a way that is both authentic and transparent is increasingly crucial.

January 30, 2025

|

A Radical Solution to the U.K. Housing Crisis: Building a New London in the Thames Estuary

How should the U.K.’s government be addressing the housing crisis? Here are four steps to a radical solution.

January 29, 2025

|

Trends to Watch: What Other Cities Can Learn From New York City’s Conversion Boom

As U.S. cities experience high commercial real estate vacancy rates and housing shortages, developers have an opportunity to invest in and convert stranded assets.

January 29, 2025

|

What Retail Can Learn From Chinatown: 3 Ways to Create Thriving Third Places

Looking towards San Francisco’s Chinatown as a case study, here are three key strategies to create a thriving third place.

January 29, 2025

|

What Are Corporate Real Estate Executives Planning for 2025?

A look at what office space portfolio modifications and space allocation strategies CRE leaders are anticipating and planning for the year ahead.

January 27, 2025

|

The Future Is Mixed Use: How Principles of Mixed Use Design Will Restore Our Communities

Here are four principles for creating mixed-use environments that will future-proof real estate.

January 27, 2025

|

The New Era of Retail Banking Is Here

To stay relevant, banks must transform branches into spaces that go beyond transactions, creating experiences that resonate with a new generation of consumers.

January 21, 2025

|

5 Design Considerations for Authentic Specialty Market Experiences

Though the retail and dining sector has struggled with pandemic recovery and rising costs, the specialty markets subcategory is thriving.

January 21, 2025

|

The Future of Healthcare Is Anchored in Its Communities

Community health hubs will play a vital role within an integrated ecosystem of health and care.

January 17, 2025

|

3 Ways Gensler Is Designing for a Zero-Carbon Future

The most successful buildings of the future will contribute to the well-being of the environment while bringing their carbon emissions to zero.

January 16, 2025

|

Why Quality in Commercial Office Space Hinges on Workplace Experience

Demand is surging for premium office environments that deliver an effective workplace and a great work experience.

January 14, 2025

|

Designing a Community-Based Workplace for Valley Bank

Gensler partnered with SJP Properties and Valley Bank to envision both the base building and a community-driven workplace interior for Valley’s employees.

January 13, 2025

|

Avoiding Fear-Based Decision-Making to Foster Positive In-Store Retail Experiences

How deliberate design decisions can boost brand recognition and connect with customers.

January 10, 2025

|

Removing Behavioral Health Stigmas Through Elevated, Strategic Design

We designed a revolutionary new kind of emergency facility to break down social and systemic barriers surrounding behavioral health care.

January 09, 2025

|

The Future of Energy: How Small Modular Reactors Are Changing the Game

As the global demand for energy soars, small modular reactors are emerging as a key player in the race to meet this need with clean, efficient power.

January 08, 2025

|

How Gaming Can Transform Activation and Transition Planning for New Healthcare Campuses

A gamified approach to training can help educate and engage staff when transitioning to new healthcare facilities.

January 08, 2025

|

How AI and Emerging Technologies Will Transform the Future of Labs

From AI and machine learning to quantum computing, we explore how technological advancements are redefining how scientists work.

January 07, 2025

|

Bringing Spaces to Life: The Integral Role of Service Design in the Design Process

Service design acts as a bridge that connects the physical design of a space with the user-centric experiences within it.

January 07, 2025

|

When It Comes to Workplace Design, Beauty Drives Performance

Beauty plays a crucial role in driving workplace performance, going beyond mere aesthetics to shape overall functionality and impact the employee experience.

January 06, 2025

|

A Field Guide to Authentic Amenities

To create authentic amenities that workers truly want, designers and companies should think outside the box.

December 19, 2024

|

The Campus as a Catalyst: Combining Student Needs With Institutional Goals

Here are some key strategies for differentiating a university campus, improving retention, and reimagining underutilized spaces to optimize real estate.

December 17, 2024

|

A New Approach to London’s Dated Offices

To revitalise London’s dated office building stock, we must make these environments relevant and capable of attracting the best tenants and talent.

December 16, 2024

|

Workplace as a Service: A Thought Experiment in Office Evolution

The concept of Workplace as a Service challenges traditional notions about work environments. Will this new design perspective help the office remain relevant?

December 12, 2024

|

Trends to Watch: The Future of Entertainment in the Built Environment

Gensler’s Entertainment leaders discuss the opportunities shaping the future of entertainment, from immersive experiences to entertainment districts.

December 11, 2024

|

Trends to Watch: The Future of Cities Relies on Multiuse Districts

Gensler’s Mixed Use & Retail Centers leaders discuss the opportunities shaping the future of cities and multiuse districts.

December 10, 2024

|

Trends to Watch Shaping the Future of Mobility and Transportation

Gensler’s mobility and transportation leaders discuss the biggest trends shaping the industry, from micromobility to electrification.

December 10, 2024

|

Trends to Watch: Building City Identities to Become Destination Brands

How can brand positioning and a compelling narrative help cities create global destinations and build strong brand advocates?

December 06, 2024

|

Trends Shaping the Industrial Market in Latin America

We explore some of the key trends, innovation, and strategic design shaping the industrial sector in the region.

December 05, 2024

|

Design for Laboratory Resilience: A Compliance Approach to Climate Risk Assessment

Innovative sustainable design of laboratory buildings must factor in risk of regional natural disasters and affected communities.

November 22, 2024

|

The Secret to Paris 2024’s Olympic Success? Reuse, Temporality, and Legacy

How an innovative, sustainable, and cleverly timed approach helped Paris avert the pitfalls many cities face when hosting the Olympic Games.

November 22, 2024

|

How Communities Can Benefit From Mixed-Use Data Center Integration

As suburban communities restrict new data centers, innovative master planning development is challenged with integrating critical facilities into mixed-use settings.

November 13, 2024

|

Designing for the Future of Theater and Immersive Entertainment

Our Media and Entertainment leaders discuss what’s next for immersive theater and performing arts venues.

November 12, 2024

|

Climate Resilience in the Latin American Caribbean: Challenges and Opportunities

To mitigate the effects of climate change in the region, we must adapt cities, strengthen infrastructure, and protect vulnerable communities.

November 12, 2024

|

Office-to-Residential Conversions: What Boston Can Learn From New York’s Momentum

New York City’s conversion success story offers valuable lessons for Boston as it seeks to address its own housing shortage amid a surplus of office space.

November 11, 2024

|

Realizing Virsona’s Vision for Interactive, Community-Driven Gaming Spaces

Gensler and social gaming startup Virsona discuss the opportunity to create in-person communal spaces for one of the country’s most popular pastimes: video games.

November 11, 2024

|

How Immersive Food and Beverage Experiences Are Redefining Hospitality

Food and beverage spaces have unique potential as experiential destinations that authentically convene community in a way that is familiar, universal, and transformative.

November 06, 2024

|

Trends Shaping the Future of Retail in Latin America

Embracing cultural identity, technology, and sustainability is key to engaging consumers in the region.

November 04, 2024

|

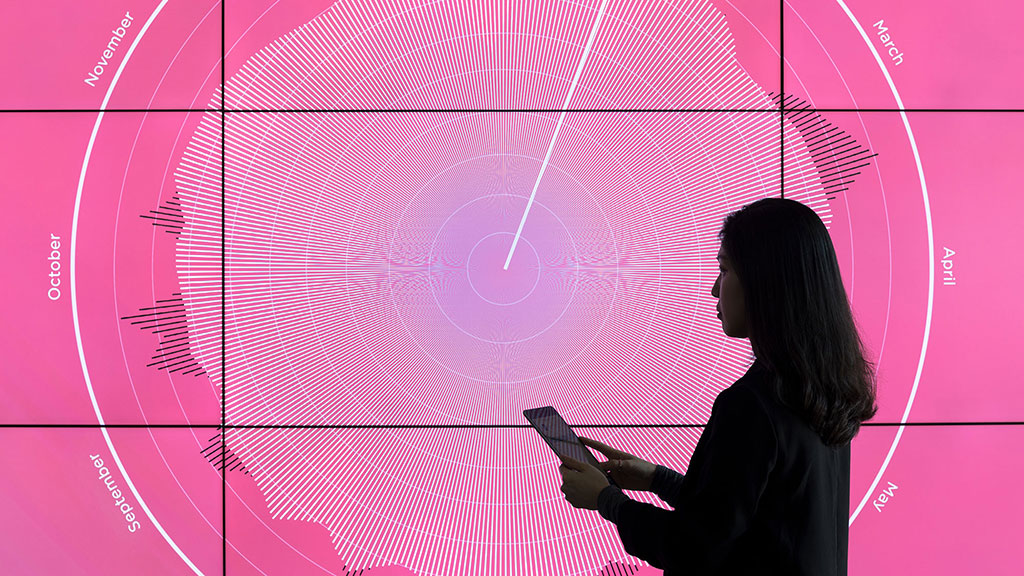

Reimagining Digital as an Enhanced Building Material

As technology becomes more invisible, we are merging physical and digital experiences to redefine how digital is considered in the built environment.

November 04, 2024

|

The Powerful Influence of Experience Design in Transforming Retail

The intersection of retail and experience design yields curated atmospheres that foster community connection and strengthen brand loyalty.

November 01, 2024

|

Redefining the Workplace for a New Era of Productivity and Engagement

This new era of work is not about obligation but about crafting a compelling experience that draws people in and encourages them to grow personally and professionally.

October 30, 2024

|

10 Workplace Trends for 2025: What’s In and What’s Out?

The workplace is evolving beyond a collection of experiences and becoming a space designed to foster intentional transformations.

October 30, 2024

|

What Two Mixed-Use Districts Reveal About Successful Retail and Placemaking

Lessons from two mixed-use destinations in Texas reinforce the value of adaptability and careful placemaking for large, retail-centered developments.

October 29, 2024

|

Face-to-Face Work and Aging Building Stock – How Can We Make Sense of French Workers’ Contradictory Attitude Towards Their Office?

There is an inextricable paradox in the attitude of French workers towards their workspaces.

October 17, 2024

|

4 Considerations for Implementing a Better Self-Checkout Experience

When done right, self-checkout can improve efficiency without sacrificing experience.

October 16, 2024

|

Designing Workplaces to Strengthen Connection and Combat Loneliness

The workplace plays a key role in fighting against the growing loneliness epidemic.

October 15, 2024

|

How Your Workplace Can Supercharge Performance

What workplaces can learn from the gym and the football pitch about creating environments that inspire workers to stretch, develop, and achieve.

October 10, 2024

|

The Evolution of Sports Venue Brand Integration: From Simple to Sophisticated

The new landscape of brand in sports is more sophisticated than ever.

October 09, 2024

|

Gensler Voices: Ariadna Hernandez on Design’s Greatest Strength

Ariadna Hernandez, a designer for Gensler Washington, D.C., shares how design can improve lives from multiple angles.

October 09, 2024

Architects Must Design for a New Age

For the first time in the history of our profession, architects are now outliving their buildings. How can we design with impact and keep up with the rapid speed of change?

October 08, 2024

|

Smart Design for Smart Manufacturing: Five Ways Manufacturing Has Evolved

In a market poised for significant growth, these markers of change present opportunities in both the near and long-term.

October 08, 2024

|

Emerging Trends in Climate Action From Climate Week NYC

Signals that the climate dialogue is evolving to meet the urgent need for impact at scale.

October 03, 2024

|

Using Narrative Design and Local Context to Create Authentic and Memorable Hospitality Experiences

Gensler's global leaders for Hospitality and Experience Design discuss the intersection of these two industries and their process for creating memorable destinations.

October 02, 2024

|

A Story of Transformation: Hyatt’s Unique Blend of Community and Hospitality

Strategies for repositioning an aging hotel ground floor into a community destination.

October 01, 2024

|

What Spa and Wellness Spaces Can Teach Us About Transforming Behavior

Luxury hospitality and spa experiences are leading the charge in changing how we experience and interact with technology.

October 01, 2024

|

The Perpetual Asset: Design for an Evolving Market

What if we could diversify a real estate portfolio with just one building?

September 25, 2024

|

Expanding New Frontiers: Redefining Hospitality in Latin America

From personalizing experiences to deepening cultural immersion, here’s how hospitality is evolving in LATAM.

September 25, 2024

|

Gensler Voices: Cristina Ziegler McCoig on Communities and Design

Cristina Ziegler McCoig, a designer for Gensler San Antonio, shares how a focus on local aligns with universal design principles.

September 25, 2024

Gensler’s D.C. Office Expansion, Renovation, and a Groundbreaking New Way to Break Down Broadloom Carpet

An office expansion pushes ideals around material reuse in a circular economy, sustainability, and workplace design.

September 23, 2024

|

Quantity and Quality: Leveraging Office-to-Senior Living Conversions to Increase Capacity and Lifelong Well-being

Office-to-residential conversions have helped reduce vacancy rates and unlock housing. It’s time to repurpose the solution to meet the growing demand for senior living.

September 23, 2024

|

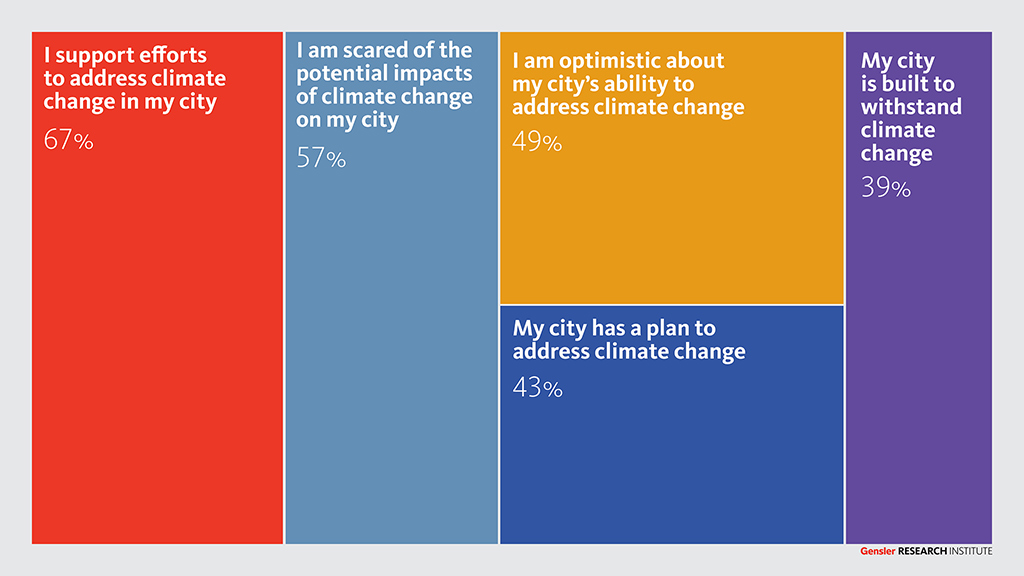

Four Big Takeaways From Gensler’s New Global Climate Action Survey

What is the state of climate change perceptions in 2024?

September 18, 2024

|

Regional Revitalization: Designing for Impact in the Middle East

Tim Martin, former Gensler Middle East Managing Director and Steven Velegrinis, Gensler Middle East Design Director, discuss designing for the region’s revitalization opportunity.

September 17, 2024

|

The Shift to Extremes: Rethinking Office Design

Modern offices are increasingly designed with extremes in mind, featuring specialized spaces for both hyper-focus and hyper-collaboration.

September 13, 2024

|

The Future of D.C. as the Capital of Creativity

A conversation on the shifts and opportunities that could transform our nation’s capital and redefine its role on the global stage.

September 12, 2024

|

Five Benefits of Leaning into Brand Identity and Culture for Office Design

Learn how Synopsys’ new workplace drives productivity and connectivity.

September 12, 2024

|

The “Mental Load” and Its Effect on Athlete Performance

We can help reduce athletes’ mental load by including specific amenities in training facilities and giving them the space and time to focus on being at the top of their game.

September 12, 2024

|

Gensler Voices: Francesca Alchanati on The Profound Impact of Design

Francesca Alchanati , a designer for Gensler Washington, D.C., shares how design can help spaces be inclusive for all.

September 12, 2024

Designing Safe, Walkable Cities for Future Generations of Children

Thoughtful urban design can transform cities into vibrant, inclusive spaces where children can thrive, connect, and grow.

September 11, 2024

|

How Large, Adaptable Multi-Purpose and Event Spaces Are Transforming the Financial Services Workplace

Major financial institutions are incorporating large, multi-purpose event spaces into their new office designs — even in cities where square footage comes at a premium.

September 05, 2024

|

How to Create a Multigenerational Workplace

Here are six strategies organizations can use to cultivate environments where individuals of all ages feel valued, engaged, and empowered.

September 05, 2024

|

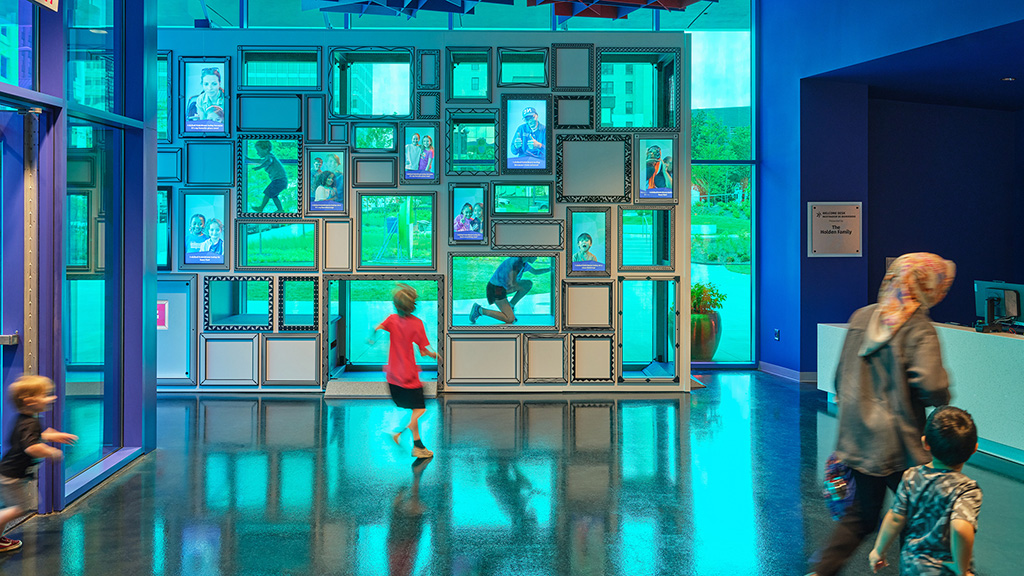

Bringing Community to the Community Center

In Houston, Gensler helped reimagine the Evelyn Rubenstein Jewish Community Center as a place that celebrates the Jewish community in every moment.

September 04, 2024

|

Imagining a Smart Recycling Reward System That Transforms the Way We Look at Trash

By transforming recycling into a rewarding, interactive process, we can inspire collective action to revolutionise waste management.

September 04, 2024

|

Beyond the Screen: Exploring the World of Museums and Experiential Technology

Digital experiences in museums, exhibits, and other interpretive spaces go beyond the screen for dynamic and memorable storytelling.

September 03, 2024

|

Creating a Range of Entry Points to Engage New Museums Audiences

Our Culture & Museums and Entertainment and Experience Design leaders to discuss what’s next for museums and cultural spaces.

September 03, 2024

|

The Evolution of the Museum

Unlike the institutions of the past, modern museums can flourish and differentiate themselves by being more forward-looking, community-driven, dynamic, and engaging.

September 03, 2024

|

Gensler Voices: Meredith Flanagan on Life at Gensler Beyond Design

Meredith Flanagan, a workplace experience manager for Gensler Washington, D.C., shares her perspective creating experiences for her Gensler office.

August 29, 2024

Conversions for Healthcare:

10 Takeaways for the Future

As healthcare systems shift to a new model of distributed care, adaptive reuse of older buildings will be an important strategy to sustainably achieve their goals.

August 27, 2024

|

Creating Inclusive Spaces by Designing for Neurodiversity

Designing for neurodiversity is an essential evolution in our drive to craft inclusive environments that support productivity, well-being, and employee satisfaction.

August 22, 2024

|

The Impact of Inclusive Design on Children’s Health and Happiness

By using inclusive design strategies in city and urban planning, we can build spaces that allow children to flourish, learn, play, and grow.

August 21, 2024

|

Uncovering Growth: Wellness Real Estate Across the Market

An increased emphasis on physical, emotional, and social health has had a significant impact on the goods, services, and spaces that support peoples’ overall well-being.

August 21, 2024

|

Insights Into the Pandemic’s Impact on Student Well-Being

Our research explores how the shift out of the pandemic is impacting student relationships, motivation, and emotional well-being.

August 21, 2024

|

6 Solutions for Designing a More Inclusive Workplace

In today’s changing work landscape, it’s critical to design environments where everyone feels safe, supported, and welcome.

August 16, 2024

|

Inclusive Design for the 21st Century Library

Exploring strategies to create universally welcoming and functional libraries that cater to their communities.

August 16, 2024

|

Learning on the High Street: A Vision for the Future

Addressing digital inequality is vital to improving educational outcomes and influencing future innovation, economic prospects, and societal well-being.

August 14, 2024

|

Are Educators and Campus Staff Ready for an Unassigned Workplace?

In the age of hybrid work, campuses have an opportunity to explore new approaches to workspace, specifically shared and unassigned space for staff and educators.

August 13, 2024

|

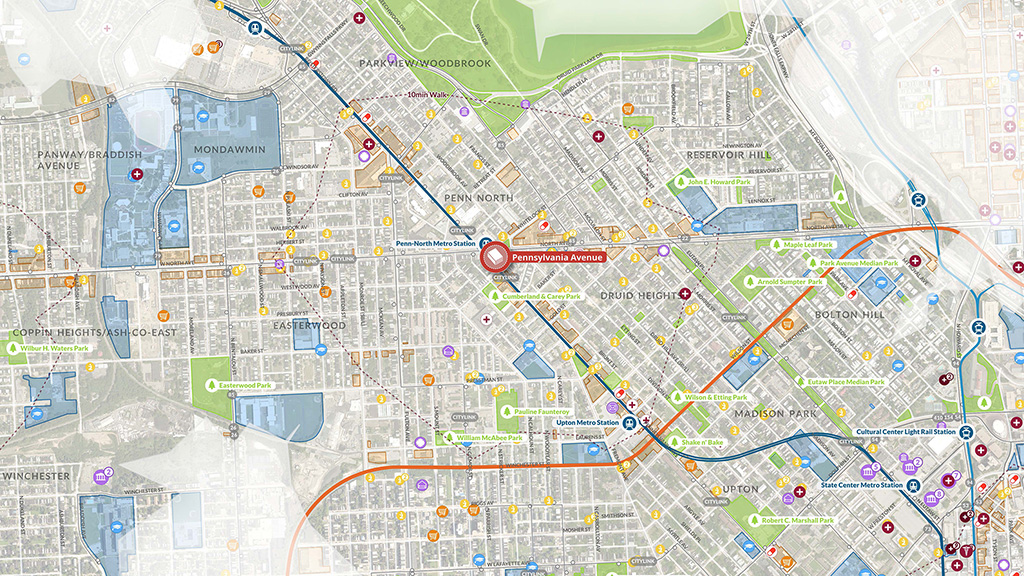

A New Tool Helps Organizations Maximize Their Community Impact

Gensler’s Urgency Index helps institutions make informed decisions that amplify their impact by locating in the communities that need them most.

August 13, 2024

|

How Urban Design and Educational Spaces Can Combat Child Loneliness

Through thoughtful urban design, we can create inclusive, supportive environments where children can safely explore and learn outside traditional classroom settings.

August 12, 2024

|

Reflecting on the Paris 2024 Olympics: A Catalyst for Urban Transformation and Sustainability

A look at how the key trends emerging from the 2024 Summer Olympics are creating a more inclusive and sustainable future for sports and urban development.

August 09, 2024

|

A New Story of Design Starts in Monterrey, Mexico

With its vibrant academic scene and growing industrial and logistic businesses, Monterrey is one of the bright spots in a booming Mexican economy.

August 07, 2024

|

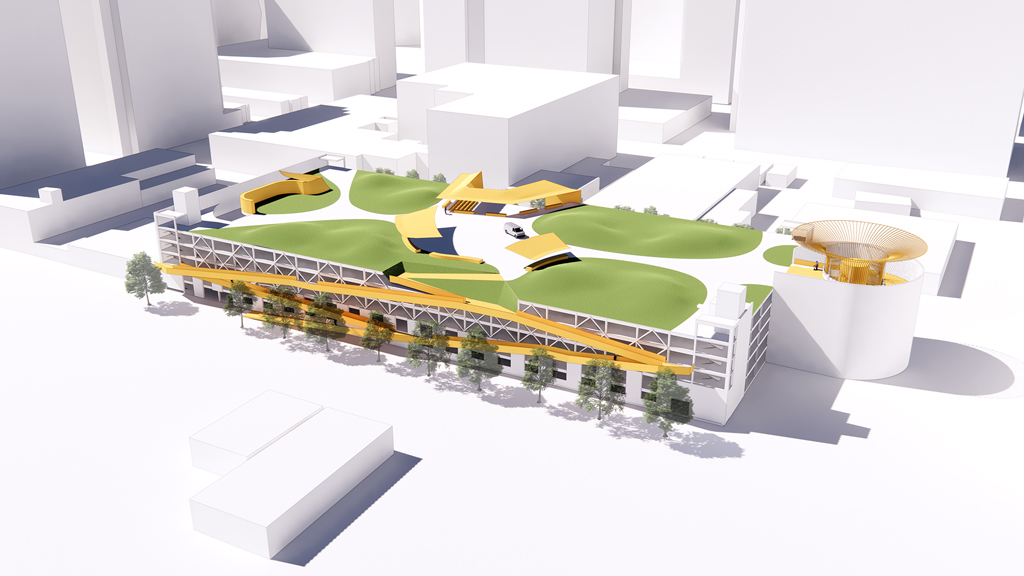

A Future-Proofed Garage in the Heart of Silicon Valley

Near Google’s headquarters in Mountain View, Alta Garage was designed with a second life in mind — one that is not limited to parking.

August 06, 2024

|

How Modern Training Centers Can Shape Tomorrow’s Champions

Helping athletes achieve their best, training centers and human performance labs (HPLs) are playing more important roles than ever to support competitors.

August 05, 2024

|

The Power of Trust in Experiential Design

Humans have a deep biological need for safety, and when we design for this need, it lets us also design for an experience of emotion that leads to meaningful human connection.

July 31, 2024

|

Worldbuilding: Creating Transformative Experiences With Narrative Design

When narrative is leveraged as a tool for design, it helps to drive emotional connection and the sense of a shared experience.

July 31, 2024

|

How the Olympics and Paralympics Can Shape Cities in New Ways

A look at the legacy, equity, and sustainability shaping the Games, and how this event can unlock a city’s future potential while showcasing it in novels ways.

July 31, 2024

|

The 5 Attributes That Define an Immersive Experience

When successful, immersive experiences give people a chance to connect deeply with the present moment and with others around them.

July 30, 2024

|

Conversations on the Intersection of Design and Disability Inclusion

Members of ADAPT, Gensler’s affinity group for disabled and/or neurodivergent staff share how design, and working in the industry, can be more inclusive for all.

July 30, 2024

|

Data Keeps Us Going:

How Data Centers Power Society

In today’s digital age, data, and data centers, have become as essential a utility as electricity or water.

July 29, 2024

|

The “Five I’s” of Design

By embracing imagination, initiative, inclusion, intention, and impact, we can elevate the human experience through design.

July 26, 2024

|

How Technology Is Redefining the Fan Experience at Sports and Music Venues

In this Q&A, our Digital Experience Design and Sports leaders discuss how technology is currently being used to streamline venue operations and enhance the fan experience.

July 24, 2024

|

Gensler Voices: Justin Rankin on The Duty of Design

Justin Rankin, a practice area leader for Gensler Austin, shares more about habits and design impact.

July 24, 2024

Elevating the “Standing Room Only” Fan Experience in Sports Venues

In recent years, sports design focused on the premium fan experience. But how can we cater to the standing-room only crowd and make them feel part of the venue experience?

July 23, 2024

|

Small Upgrades, Big Impact: How Sports Facilities Can Enhance the Fan Experience and Deliver ROI

Smaller projects within a sports facility create opportunities to keep a stadium fresh and transform fan experiences in targeted ways.

July 23, 2024

|

Reimagining North Michigan Avenue: A New Era for Chicago’s High Street

Gensler’s study envisions a series of interventions to create an engaging experience on one of the world’s most iconic high streets.

July 18, 2024

|

Tech Is Broadening Its Impact by Embracing Communities

To appeal to top talent, tech companies have pushed their focus beyond their workplaces to embrace their surrounding neighborhoods.

July 18, 2024

|

Designing with Intention: Creating Emotional Connections Through Immersive Experiences

In this Q&A, Gensler’s global leaders of Digital Experience Design and Entertainment unpack the concept of experiential architecture and what makes an immersive experience.

July 17, 2024

|

Gensler London’s Commitment to a Sustainable Workplace

New to the U.K. market, the NABERS Tenancy Certification aims to help owners and tenants measure their buildings’ environmental performance and identify areas for improvement.

July 17, 2024

|

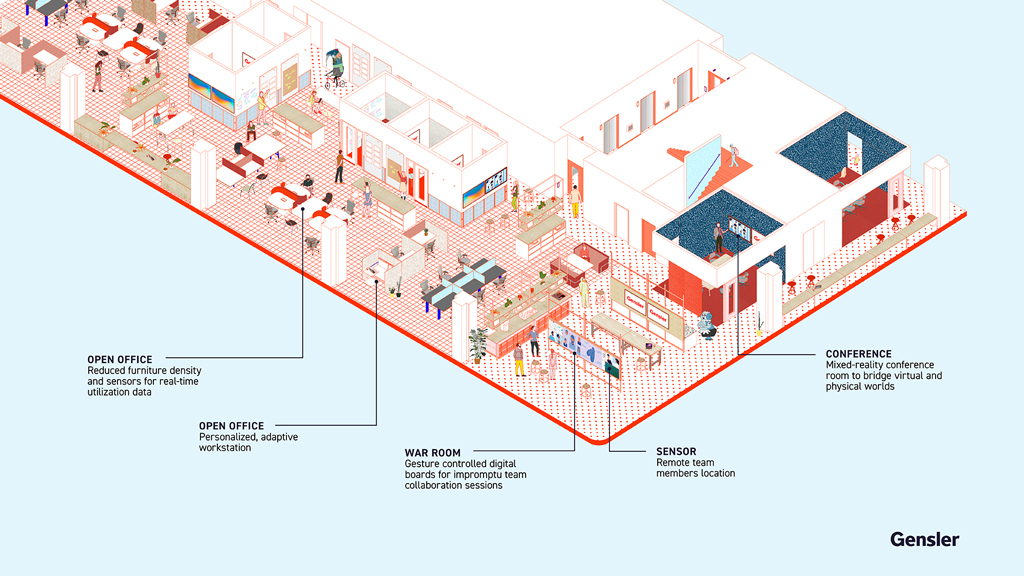

The Future of Workplace Experience Is Here: How AI Is Transforming Spaces

The advanced integration of AI into physical environments has the potential to reimagine spaces as more efficient, connective, and inspiring.

July 16, 2024

|

How the Tech-Enabled Workplace Can Create Better Hybrid Experiences

How can we design workspaces that benefit everyone, regardless of whether they have a seat at the conference room table?

July 16, 2024

|

Be Bold Not Beige: The Power of Colour to Shape Everyday Experiences

From boosting productivity in the workplace to soothing the soul at home, colour can transform the places where we live, work, and play.

July 12, 2024

|

Office-to-Residential Conversion: A New Value Proposition for the German Market

This adaptive reuse strategy represents a value proposition that could help the country meet housing demand and achieve decarbonisation goals.

July 02, 2024

|

How Design Can Integrate Social Value Into Residential Developments

Design plays an integral role in fostering social value within residential areas.

July 02, 2024

|

Maximizing Building Portfolio Value: The Crucial Role of Lease Support Services and Up-to-Date BOMA Records

Lease support services are no longer a nice-to-have but a necessity for building owners and managers to stay ahead in the competitive real estate market.

June 28, 2024

|

Trends to Look for at the 2024 Summer Olympics and Paralympics

How Paris 2024 is achieving more with less, and the trends shaping the Games wide open.

June 27, 2024

|

Maximising Urban Space: 3 Strategies for Solving the U.K.’s Housing Crisis

Addressing the U.K. housing shortage will require a multifaceted, strategic approach, recognising the urgent need for land to accommodate new homes and infrastructure.

June 26, 2024

|

Gensler Voices: Abbey Rampy on Following Her Gut

Abbey Rampy, a designer for Gensler Charlotte, shares the best career decision she’s made.

June 26, 2024

Design as a Superpower in the Senior Living Industry

Excellent design of senior living facilities prioritizes well-being in ways that should be automatic for all types of design.

June 26, 2024

|

Laying the Groundwork for Climate Preparedness

Gensler’s Resilience Preparedness Framework develops concrete actions that designers can take to address climate shifts.

June 24, 2024

|

Designing the Future Workplace for a Growing Professional Services Firm

How a collaborative design partnership evolved this national accounting, tax, consulting, and business advisory firm’s workplace experience.

June 24, 2024

|

Prototyping the Hospital of the Future

By prioritizing critical care, streamlining support services, and designing for long-term adaptability, hospitals can create a more sustainable future for healthcare.

June 21, 2024

|

Navigating Federal Resources for Office-to-Residential Conversion

As building owners in the U.S. face the prospect of defaulting on office buildings, many are turning toward the federal government for a financial lifeline.

June 18, 2024

|

San Francisco Is on the Brink of a Revival, Fueled by AI, Innovators, and Investors

Contrary to reports of the city’s demise, more people are feeling satisfied with their living experience.

June 18, 2024

|

Luxury + Convenience: Why Branded Residences Are in Demand Across the Globe

In the residential sector, we’re seeing an increased demand for high-end, branded residences that offer hotel-style services and amenities.

June 17, 2024

|

Pearl House: Explore the Transformation of New York’s Largest Office-to-Residential Conversion to Date

Gensler and Vanbarton Group detail how they partnered to convert a 1970s office tower into a thriving residential community in New York’s Financial District.

June 12, 2024

|

Are ‘New Towns’ the Solution to the U.K. Housing Crisis?

The U.K. is struggling to provide enough housing for its growing population. Now is the time for a more radical approach to the provision of housing.

June 10, 2024

|

The Pandemic Hit New York Hard — But Its Recovery Has Been Swift

Despite facing significant challenges, New York City’s economic recovery showcases its resilience and durability in the face of disruption.

June 05, 2024

|

The Importance of ‘Carbon Storytelling’ in Future Sustainable Architecture

‘Carbon storytelling’ will be essential for sustainable buildings of the future — here’s why.

June 05, 2024

|

Gensler Voices: Jonathan Plass on How Listening Can Bring Inspiration

Jonathan Plass, a design analyst for Gensler Washington, D.C., shares his career journey in design from early influences to his favorite projects.

June 05, 2024

What’s the Recipe for Retail Success? Food

With a heightened consumer appetite for engaging social spaces, food and beverage are key ingredients for physical retail viability.

June 04, 2024

|

An Innovative Solution to Confront Mexico City’s “Day Zero”

A visionary project seeks to redefine Mexico City’s relationship with water, offering a beacon of hope in the face of scarcity.

June 04, 2024

|

From Mill Towns to Cities: How the Mass Timber Revolution Is Impacting People and the Planet

What if there was something the design industry could do to revitalize rural communities with access to abundant, renewable forest resources?

May 31, 2024

|

Introducing the Gensler Transit-Oriented Development Opportunity Index

The Gensler Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) Opportunity IndexTM is a tool for unlocking the unrealized value of existing transit stations and facilities.

May 31, 2024

|

Why Singapore’s Flexi-Time Regulations Are a Step Towards Building a More Sustainable Work Culture

New government regulations are shifting to meet the evolving needs of the country’s workforce.

May 29, 2024

|

Trends to Watch: How Media Workplace Priorities Have Evolved in 2024

Gensler’s latest research and project work has uncovered new ways the design of the media workplace can deliver what employees want and need in an office experience.

May 28, 2024

|

Why Hospitality Must Adopt the “Leave No Trace” Mindset

By embracing “Leave No Trace” ideas, we can raise the bar on placemaking that brings people together, elevates natural and urban spaces, and preserves the Earth.

May 23, 2024

|

How Public Libraries Are Building Community

The public library’s mission has changed from a simple repository to a community center, where learning experiences, cultural resources, and community interaction take place.

May 22, 2024

|

Mexico City Is Reckoning With Explosive Economic Growth Alongside a Mounting Water Crisis

Despite an influx of capital and accelerated economic growth, Mexico City is grappling with a water shortage and affordability challenges.

May 22, 2024

|

Equitable Public Engagement for a Changing World

Equitable outcomes begin with an equitable process, and public engagement is key.

May 21, 2024

|

Singapore’s Recovery Is Challenged by High Housing Costs

Learn what Gensler’s City Pulse research reveals about how Singapore has rebounded since the pandemic.

May 16, 2024

|

Want a High-Performing Workplace? Here’s What Matters Most.

Our research identifies what makes a high-performing workplace and what design factors matter most.

May 15, 2024

|

How Workplaces in Tokyo Are Embracing Flexible Work

Tokyo is embracing flexible work to support a diverse workforce and companies are taking careful steps to design workplaces that meet modern expectations.

May 15, 2024

|

Inclusive Product Design

Should Never Exclude Style

Products that are ADA compliant are typically well-engineered, but often bulky, institutional in appearance, and emotionally dispiriting — and millwork pulls are no exception.

May 15, 2024

|

The Key to a Better Workplace? Understanding How and Where People Work Today

Our global workplace research uncovers insights into how new work patterns can help design better workplaces for the future.

May 13, 2024

|

Writing the Next Chapter of Sports and Entertainment in Kansas City

Co-CEO Jordan Goldstein and Studio Director Greg Brown detail the evolution of sports and entertainment design and why expanding into this market offers unmatched opportunity.

May 13, 2024

|

What Can San Francisco Learn From Successful Building Conversion Programs in Other Cities?

By taking cues from other cities, San Francisco has an opportunity to make it easier to repurpose buildings, address the housing crisis, and revitalize downtown.

May 08, 2024

|

What’s on the Horizon for Low-Carbon Design in the U.K.

In the last five years, the way we think about carbon in our buildings has transformed — but the biggest impacts are yet to come.

May 07, 2024

|

Post-Pandemic, London Is Drawing Back People, Jobs, and Businesses

Gensler’s City Pulse Retrospective suggests that “boomerang Londoners” are returning to London for social, cultural, and career opportunities.

May 03, 2024

|

What Gensler’s Education Engagement Index Reveals About the Future of Hybrid Learning

An exploration into the future of the hybrid learning experience.

May 02, 2024

|

Gensler’s City Pulse Retrospective Tracks the Complex Shifts in Urban Life

Our latest cities research reveals that despite pain points, the desirability of cities persists.

April 30, 2024

|

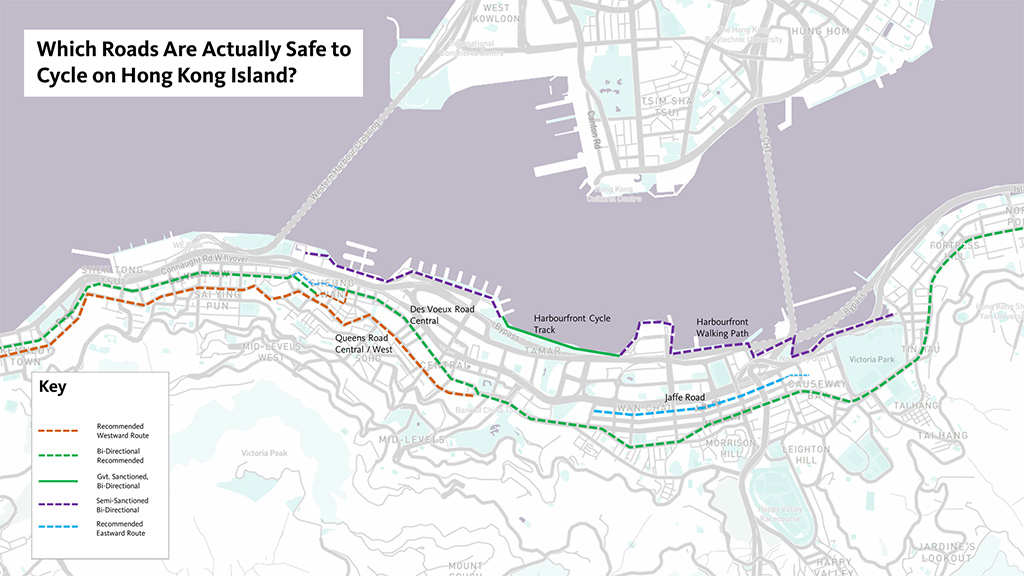

Innovations in Mobility Design Are Paving the Way for More Resilient Cities

The way people travel in, around, and between cities affects everything from urban planning to sustainability, and design plays a key role in supporting new behaviors.

April 30, 2024

|

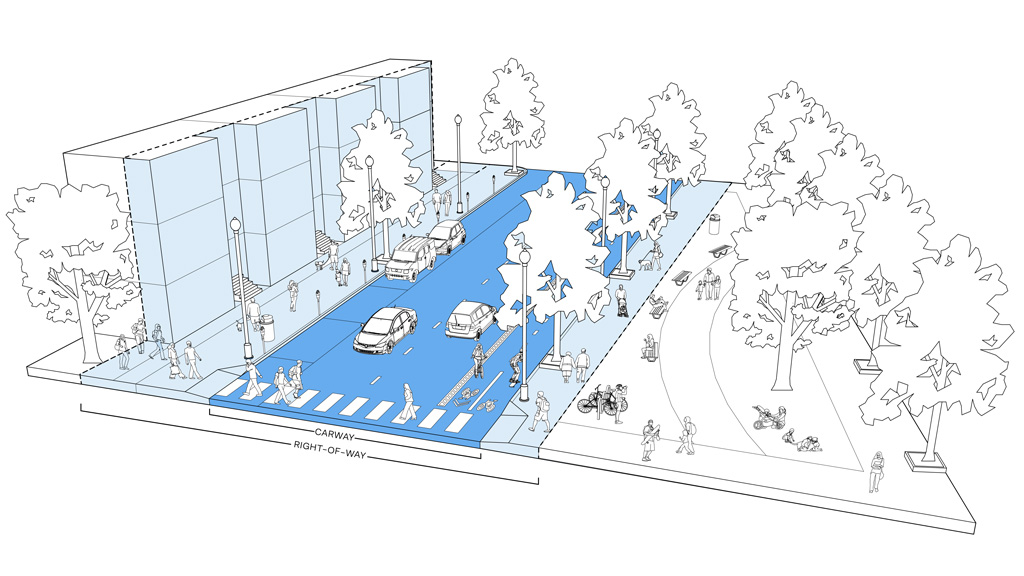

The Most Impactful Urban Infrastructure? City Streets

Gensler’s plan for Hollywood Boulevard demonstrates how rethinking city streets can revitalize cities, create healthy communities, and support sustainable mobility.

April 29, 2024

|

Beyond the Property Line: How to Design a Sustainable Material Supply Chain

We have a tremendous opportunity to think beyond the property line and holistically address impacts from the interconnected, global system of building materials.

April 25, 2024

|

Invisible Cities: Mitigating the Bird Strike Problem

With proper research and active measures, we can help solve the bird strike problem and benefit ecosystems across the globe.

April 25, 2024

|

Using Design to Bring Hope

As design professionals, how do we incorporate positive and equitable impacts into our design? How can we use the power of design to change lives and heal communities?

April 24, 2024

|

Gensler Voices: Shirin Masoudi on Her Design Inspiration

Shirin Masoudi, a designer for Gensler Seattle, shares her unique perspective on design.

April 17, 2024

4 Powerful Approaches for Putting Climate Goals to Action

We’ve identified four approaches that put organizations on a credible path to achieving climate goals.

April 16, 2024

|

Driving Sustainability Through Digital Experience Design

By lowering energy consumption, reducing e-waste, and elevating eco-friendly materials, digital experiences can become an asset in sustainability messaging.

April 16, 2024

|

Using an “All-Spokes” Approach to Optimize Lab Space

It's not just a question of space, but rather the nexus of space, people, process, operations, equipment, and technology.

April 16, 2024

|

Decarbonizing the Built Environment for a More Sustainable Future

By acting quickly and working with industry partners to develop and promote lower embodied energy materials, we can catalyze a low-carbon marketplace.

April 15, 2024

|

5 Things Developers Should Know About Mass Timber

With its inherent structural integrity and positive impact on carbon emissions, mass timber can make a big impact in tackling climate action in the built environment.

April 09, 2024

|

Global + Local Design Is a Powerful Tool for Navigating Change

At a time when deglobalization is on the rise, the role of design as an integrator has never been more critical.

April 05, 2024

|

BOMA 2024: 5 Key Changes Reshaping Office Building Measurements

Here are five improvements you need to know about the new BOMA 2024 office standard.

April 04, 2024

|

A Football Academy Designed to Empower Youth in Ghana

Right to Dream’s Ghana campus is a best-in-class facility that sets a benchmark for football academies everywhere.

April 03, 2024

|

Gensler’s Mexico City Office: A Model for the Future Workplace

A model of workplace transformation, Gensler’s new Mexico City office blends authentic Mexican culture with forward-thinking design principles.

April 02, 2024

|

Decarbonization Needs to Hit Closer to Home

If cities want to get serious about reducing their carbon impact, exploring ways to reduce the emissions of our homes is a key opportunity.

April 02, 2024

|

A Well-Designed Workplace Is a Competitive Advantage

A healthy, sustainable workplace acts as a magnet for talent — and sets a property apart in today’s competitive market.

April 02, 2024

|

Revolutionizing Child Care: The Key to Enhancing Your Return-to-Office Strategy

By offering on-site or nearby child care options, businesses can position themselves as employers of choice.

April 01, 2024

|

Trends to Watch Reshaping the Future of Cities and Urban Living

Gensler’s Cities & Urban Design leaders discuss what’s next for the future of cities.

March 29, 2024

|

Trends Shaping Sports Venue Design in the European Market

Gensler Sports leaders discuss what’s next for stadium and training facilities in Europe, and key opportunities for growth in the European market.

March 28, 2024

|

Rethink, Redirect, and Rewild: Nature-Based Design Solutions for Carbon Sequestration

By utilizing nature-based design solutions to rethink carbon sequestration in our work, we have an opportunity to make a positive impact on our net zero goals.

March 27, 2024

|

A Fresh Take on the Corporate Workplace, With Inspiration From 19th Century London

With its historic character, Francis House provided the perfect platform to create a dynamic, engaging, and holistic employee experience for Edelman’s London office.

March 27, 2024

|

A New Strategic Vision to Revitalise London’s Fleet Street Quarter

How the Fleet Street Quarter Public Realm Strategy is transforming London’s Central Business District into a vibrant, multimodal Central Social District.

March 26, 2024

|

Three Considerations for Repurposing Stranded Assets for Education

In many instances, abandoned buildings can be converted into thriving schools when they prioritize sustainability, focus on community impact, and offer urban revitalization.

March 25, 2024

|

Trends to Watch: How the Rise of Women’s Professional Sports Is Impacting Venue Design

We talked to six leaders from Gensler’s sports practice about new trends informing the planning and design for the boom in women’s professional sports teams.

March 21, 2024

|

Putting the Patient at the Center of the Health-And-Wellness Equation

Consumer culture, personalized medicine, and technology are extending conversations about well-being far beyond doctors’ offices and hospitals.

March 19, 2024

|

From Canvas to Community: The Art of Placemaking at the Moody Center

Moody Center creates a space where art, culture, and community converge, inviting visitors to become active participants in the placemaking process.

March 13, 2024

|

From Skyline to Shoreline: A Vision for Mixed-Use Spaces in Miami