Climate Action & Sustainability

Google at St. John’s Terminal

Pacific Center

NVIDIA

First United Bank

The Lighthouse

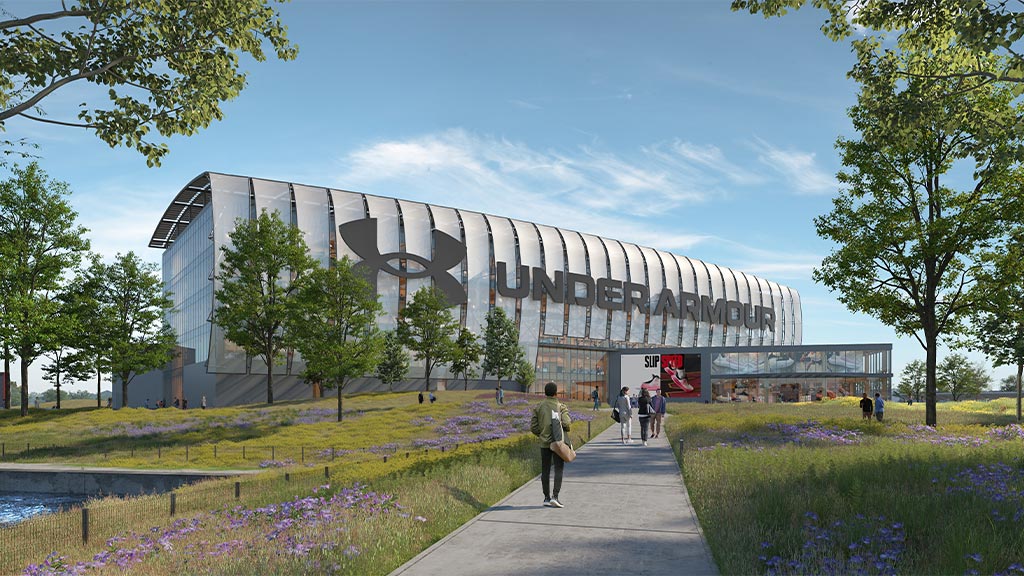

Under Armour Global Headquarters

San Francisco International Airport, T1 Net Zero Program

10 Gresham Street

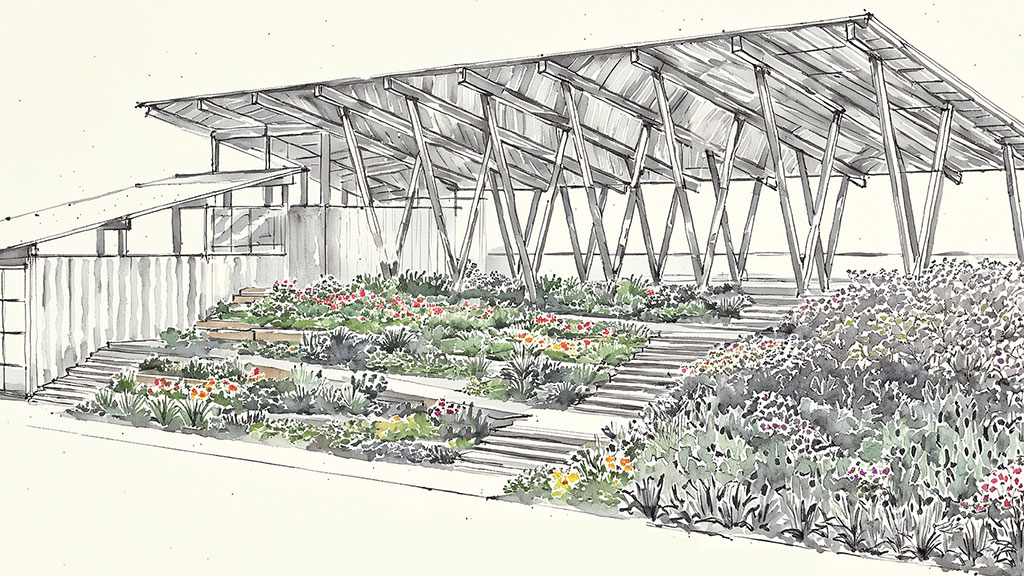

Sustainable Shade Structures

Rancho Los Amigos – Harriman

LinkedIn Omaha

American Physical Therapy Association Headquarters

CSULB Parkside North Residence Hall and Housing Administration Building

The Link

The Acre

Torre Universal Sustainability

Café Britt Headquarters

citizenM

Walmart Home Office

Holt Renfrew Sustainable Guidelines

UPCycle

Centro de Convenciones de Costa Rica

CSU Northridge Student Sustainability Center

Houston Advanced Research Center (HARC)

Etsy

U.S. General Services Administration, Federal Office Building

Santa Monica College Core Performance Center

The Power of Adaptive Reuse for a Low Carbon Future

A Playbook for Sustainable Design Education

How to Design Sustainable Digital Media Experiences

Commercial Office Building Electrification Playbook

Building for Centuries

When Rivers Rise and Wells Run Dry: Designing Water-Resilient Cities

Reducing Gypsum Wallboard Waste for a Sustainable Future

How a New Vision for Flexible Co-Living Conversions Can Support Housing Affordability

Scaling Circular Design: Key Policies, Standards, and Strategies

Climate Change Is Threatening What We Love About Cities

The Carbon Impact of a Workday

7 Myths Dogging Efforts to Fully Electrify Buildings — Let’s Bust Them

Reimagining Haussmann: Adaptive Workplace Design in the Parisian Urban Fabric

The Carbon Impact of a Workday

How London’s Green Real Estate Can Lead the Global Climate Agenda

The building industry de-risks investments with resilience strategies.

With rising urban heat and flooding, investors seek solutions that protect the long-term value of real estate. Cities and developers turn to nature-based infrastructure, resilient building retrofits, and targeted climate risk modeling to safeguard assets against escalating physical risks.

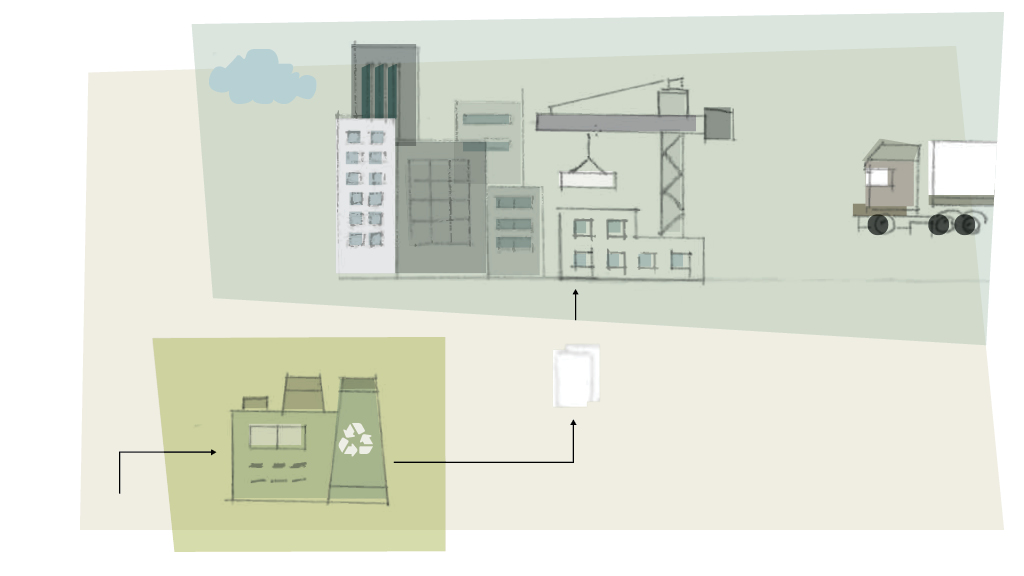

Circularity takes center stage.

Circular design reshapes the built environment. From adaptive reuse and modular design to material recovery and deconstruction, owners, developers, architects, and urban planners rethink waste as an opportunity. By treating buildings as material banks, the industry cuts carbon, conserves resources, and moves closer to net-zero goals.

AI and machine learning tools improve sustainable performance insights.

AI-driven management systems and machine learning platforms allow building owners and operators to predict, track, manage, and optimize their energy, water, carbon, occupant comfort, and air quality performance in real time.

David Briefel

Kirsten Ritchie

Gensler’s David Briefel Is Recognized As 2025’s Sustainability Leader Winner at the Planet Positive Awards

How Gensler’s AI-Powered Tool Can Guide Decisions to Advance Resilient, Sustainable Real Estate

Gensler Leads Iraq’s Largest Ecological Development

How Microsoft Is Building Its First Datacenters With “Superstrong” Hybrid Mass Timber

Reuters’ The Switch Interviewed Design Resilience Leader Rives Taylor About How Architecture Is Adapting to Climate Change

Gensler Product Sustainability Standards Reduce Environmental Impact of Architectural Interiors

How Gensler Is Reshaping Cities To Withstand Environmental, Economic, and Cultural Changes

Interior Design Named Gensler the #1 Firm on Its 2024 Sustainability Giants List

Curbed Featured the Recently Revealed Google’s St. John’s Terminal in NYC

The 2024 Women in Sustainability Leadership Awards Recognized Gensler Sustainability Director Mallory Taub

How Companies Are Prepping for California’s New Climate Emissions Law

Gensler’s Andy Cohen on How the Buildings and Cities of the Future Can Achieve Net Zero

The Pros and Cons of Building With Precast Concrete

Gensler

How To Mitigate Extreme Heat in Vulnerable Communities