From Railroads to Electric Scooters: How Mobility Shapes the City of Today and Tomorrow

By Dylan Jones

“Mobility” is a hot topic in the world of planning and urban design. From GPS-enabled electric scooters, to driverless cars, and even aerial ride-share services, disruptive mobility is on the rise. The movement of people (and stuff) deeply affects our lives. Our cities are shaped by the paths, streets, rails, airports, and ports that support the movement of people and goods. With the explosion of disruptive mobility services taking hold in our cities, it’s critical that we, as a design community, build a common language of understanding as we shape a vision for the cities of tomorrow.

People immediately think about the direct physical implications of getting from place to place, but there are less obvious ways to think about mobility. For example, the phrase “upward mobility” describes the ability to move from one socio-economic class to another; “workplace mobility” relates to the untethering of workers from place through use of connected technology; and “capital mobility” refers to the ability of capital (i.e. money) to move from place to place. All of these examples have profound impact on cities, and all of them are currently being disrupted by technology.

Given the breadth of the topic, it’s useful to have a simple model of mobility to better understand the ways in which movement impacts the form and experience of a city. A model helps organize the typological differences of various mobility structures, and acts as a lens to understand the sometimes-dissimilar nature of mobility discussions.

Mobility is composed of three distinct and interrelated components: that which is moved (the vehicle), the space and time through which movement occurs (the path), and the experience of those being moved or adjacent to the movement. Imagine the simple example of a convertible driving down a country road: the car is the “vehicle,” the road is the “path,” and the lived moment of the individuals as they enjoy the ride is the “experience.”

All mobility modes can be broken down into these three elements. Putting aside experience, consider just the vehicle and path. Cars are vehicles, roads are paths. Ships are vehicles, water provides the path. Airplanes are vehicles, air provides the path. Even a person can be considered a vehicle; for example, a hiker, where the trail is the path. Vehicles include an act of motion, paths support that motion. Vehicles are generally private or privatized, while paths are typically shared. Vehicles are technologically flexible and current, paths are generally fixed and low tech.

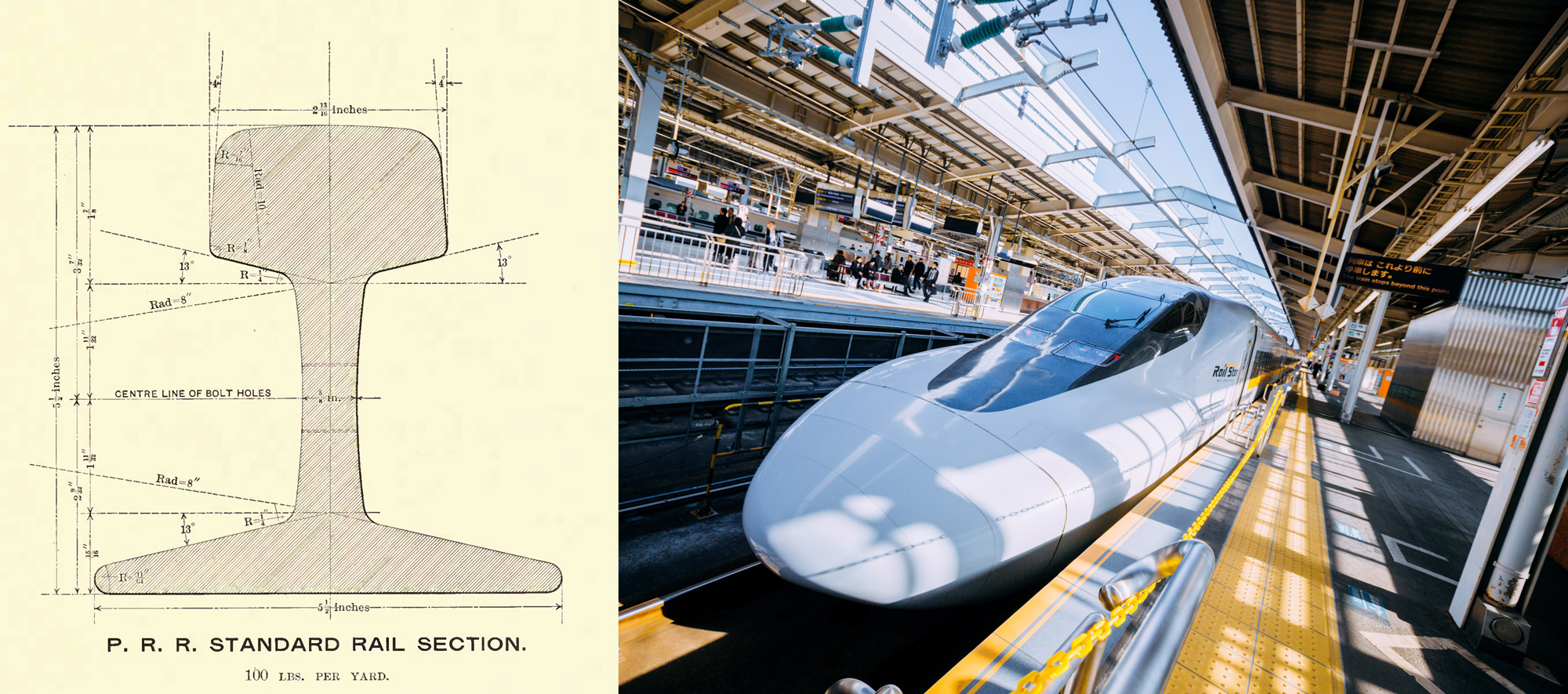

Consider two interesting, yet divergent examples: rail travel (trains) and the “Hyperloop.” Trains travel on rails, steel extrusions fixed to ties. The rails and ties have changed little in the past 150 years, but the high-speed electric trains that roll over rails are a world apart from the coal-fueled steam locomotives of the past. The technology, embedded in the vehicles, has continued to evolve and the paths (the rails themselves) have been successful because they are decidedly low-tech. This is consistent with a number of enduring modes. The most successful mobility solutions typically include a low-tech or static path combined with vehicles that can evolve freely with technology.

On the other hand, the technology proposed in the Hyperloop concept — sending magnetically levitated pods through near-vacuum tubes at high speeds — takes a completely different approach. This mode requires building cutting-edge technology into the path itself. Understanding mobility through the lens of the vehicle/path/experience model leaves us questioning the notion of embedding today’s technology, however cutting-edge it seems right now, into the long, fixed pieces of infrastructure required to make the system work.

The third component of this model, experience, is what we at Gensler care most deeply about. We always strive to leverage design to improve the lived experience within our communities. Mobility structures all come with unique and specific experiences, and literally shape the form of our communities and cities. The paths that form around specific modes shape the composition and fabric of urban space. Some older cities have been built up around foot paths, others around rail, and newer cities around automobiles. This urban fabric is itself a foundation for the way in which people connect, and it shapes the lived experience.

Vehicles connect people to each other and to the places they want to go, but they also affect the experience of communities in other ways. They may pollute, they may be noisy, they may be dangerous; on the other hand, they may offer new opportunities to connect with people and jobs, and in some cases, may even spark joy.

An understanding of the vehicle/path/experience construct will help us understand the nature of various infrastructures, along with their shaping force on the physical and lived experience. It will help us evaluate, critique, and organize new modes proliferating at an unprecedented pace. The model will help us understand the roles and responsibilities of the public and private sectors, as we move from a 20th century, mono-modal construct, to a 21st century, multi-modal construct. Finally, the model will help us leverage design so we can better connect people to place, and most importantly, to each other.

Stay tuned as we dive into various new modes, interview new players and old, and start to unpack the thorny problems that only good design can solve!