Building Transformation & Adaptive Reuse

Pearl House (160 Water Street)

The Acre

One Post Office Square Repositioning

One Raffles Quay

JC Plaza

1 St. Clair West

Folio House

135 West 50th Street

The Residences at Rivermark

Frisco Public Library

Kuntai Tower Renovation

Loffler Companies

The Mart

The Gild

Franklin Tower

Esperson 17th Level Amenity Space

The Post Office

The Book Depository

Briarlake Plaza Repositioning

Bank of America Plaza Lobby Renovations

1001 Robert-Bourassa

Metro Loft 219-235 East 42nd Street Conversion

The Francis Crick Institute at 20 Triton Street

Willis Tower Repositioning

Western Market

BizFlex

110 The Queen’s Walk

The Opportunity to Reimagine Empty Office Buildings in Mexico City

Rethinking Residential Unit Design: Lessons from Office-to-Residential Conversions

What’s Next After the Department Store? Repurposing Hudson’s Bay’s Vacant Properties

Amenity Intelligence: A Smarter Approach to Office Amenities

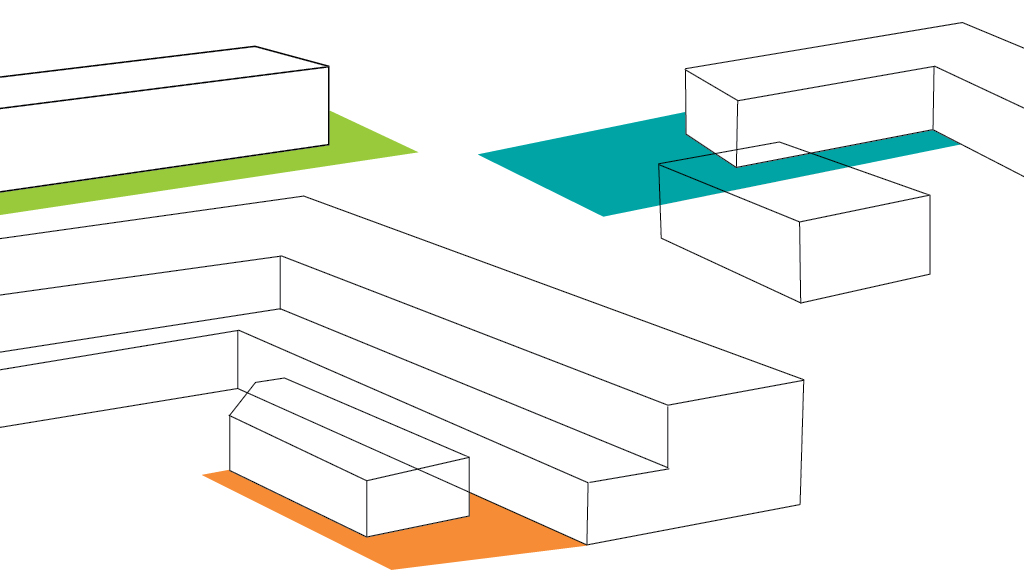

Reimagining Suburban Office Buildings with the DRAFT Framework

Revitalizing Vacant Strip Malls for Community Growth

Building for Centuries

Seattle’s Office-to-Residential Future: How Policy and Design Will Transform Downtown

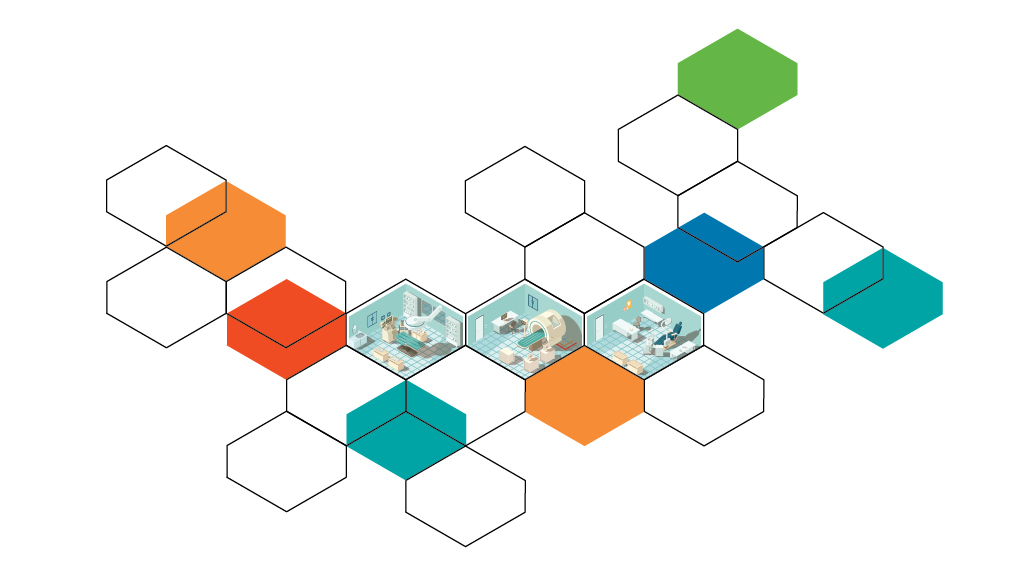

Converting Office Space for Outpatient Care

Transforming Pier 94: A Collaborative Journey in Sustainable Design and Adaptive Reuse

How a New Vision for Flexible Co-Living Conversions Can Support Housing Affordability

San Francisco’s AI Boom Is Our Chance to Build a People-First City

Birmingham Living: The Next Chapter

Scaling Circular Design: Key Policies, Standards, and Strategies

7 Myths Dogging Efforts to Fully Electrify Buildings — Let’s Bust Them

Reimagining Haussmann: Adaptive Workplace Design in the Parisian Urban Fabric

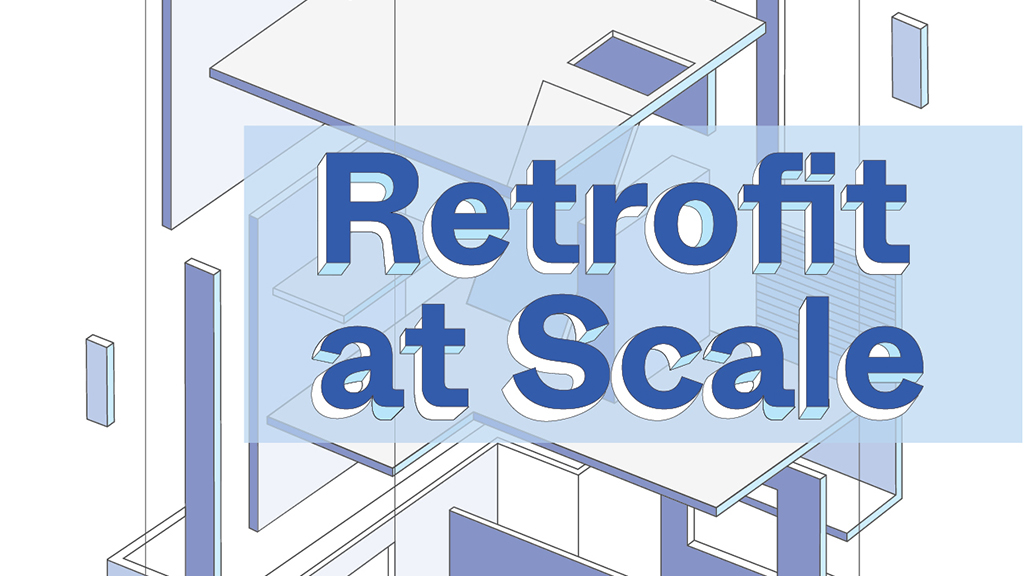

Retrofit at Scale: A New Blueprint for Investible Urban Development

How San Francisco Can Apply Startup Culture to Unlock Housing Solutions

5 ‘Out of the Box’ Strategies for the Retail Real Estate Market

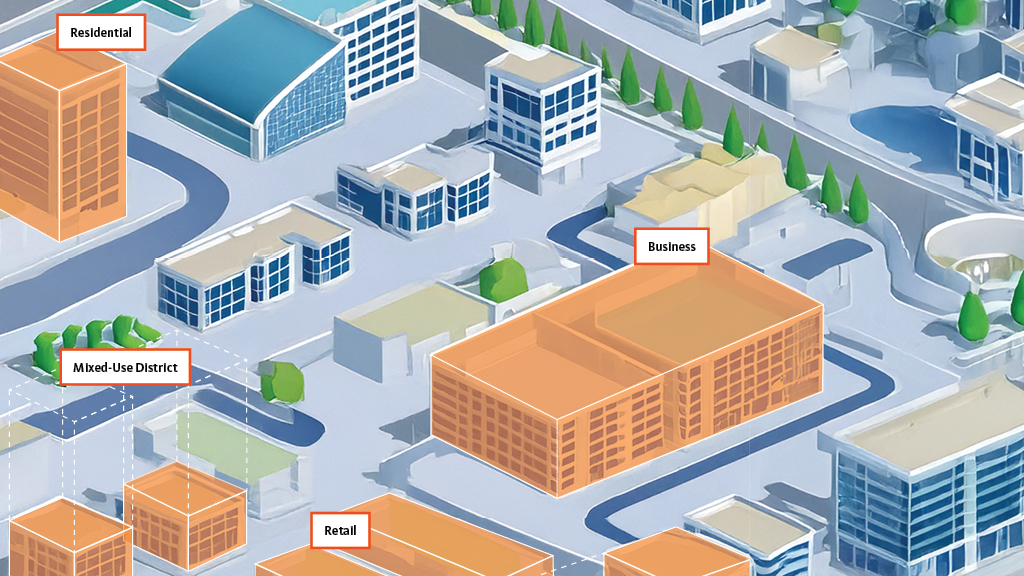

Data shapes conversion investments, one neighborhood at a time.

Data-driven targeting of specific neighborhoods and corridors reshapes where conversion investment goes to achieve the right mix of housing, retail, and amenities. This demands design approaches that decode existing building conditions and tailor to context, whether light-touch upgrades, historically sensitive interventions, or deep structural reconfigurations.

Converting single-use buildings into mixed-use spaces builds long-term strength.

Office conversions that plan for multiple future uses — not just one — give buildings a second life and long-term value in an unpredictable market. By integrating different types of spaces, developers can reduce operational costs, diversify income streams, and create resilient ecosystems that serve both tenants and communities.

Policy determines the pace of conversions.

Engaged cities streamline zoning and policy, aligning codes, and offer incentives to unlock waves of viable projects. In contrast, those with rigid or contradictory regulations risk continued stagnation. Policy, financial feasibility, and civic attitude are now the foundation for any successful reuse effort.

Amy Campbell

Harry Cliffe-Roberts

Mary Faria

Steven Paynter

Gensler’s Robert Fuller Shares the Challenges and Lessons Learned From Converting Over 5 Million Square Feet of NYC Office Space

CBS News Colorado Interviews Gensler’s Alex Garrison on Conversion Plans To Preserve the Urban Fabric of Denver

The Wall Street Journal Featured Gensler’s Reimagined 750 Third Avenue on New York’s Conversion Boom

Wallpaper Spotlights Gensler’s Reimagining of The Acre in London’s Covent Garden

The Gensler-Designed Pearl House Spotlighted in RentCafe Report on Chicago’s Conversion Boom

How Office-to-Residential Conversions are Reshaping Midtown Manhattan, Including Gensler’s Conversion of the Pfizer Headquarters on 42nd Street

Chicago Tribune Interviewed Gensler Hospitality Leader Lori Mukoyama About Reimagining Historic Buildings As Hotels

How NYC’s City of Yes Initiative Benefits Manhattan’s Office to Residential Conversions

BBC Spotlights Policy Shifts and Ongoing Building Conversions in Midtown Manhattan

Bloomberg CityLab Explores How Downtowns Can Lure New Crowds With a Broader Range of Housing

Gensler’s Office-to-Residential Conversion of Pearl House Honored with 2025 ULI Americas Award for Excellence

Gensler and Opportunity London Publish ‘Retrofit at Scale’ — a Definitive Guide to Unlocking Commercial Retrofit

Propmodo Highlighted a New Report on Converting Vacant Office Buildings Into Housing

New Study Offers Data-Driven Approach for Office-to-Housing Conversions

The Architect’s Newspaper Interviewed Robert Fuller and Peter Wang on Gensler’s Office-to-Residential Work