A How-to for Creative Placemaking and Tactical Urbanism

By Carolyn Sponza

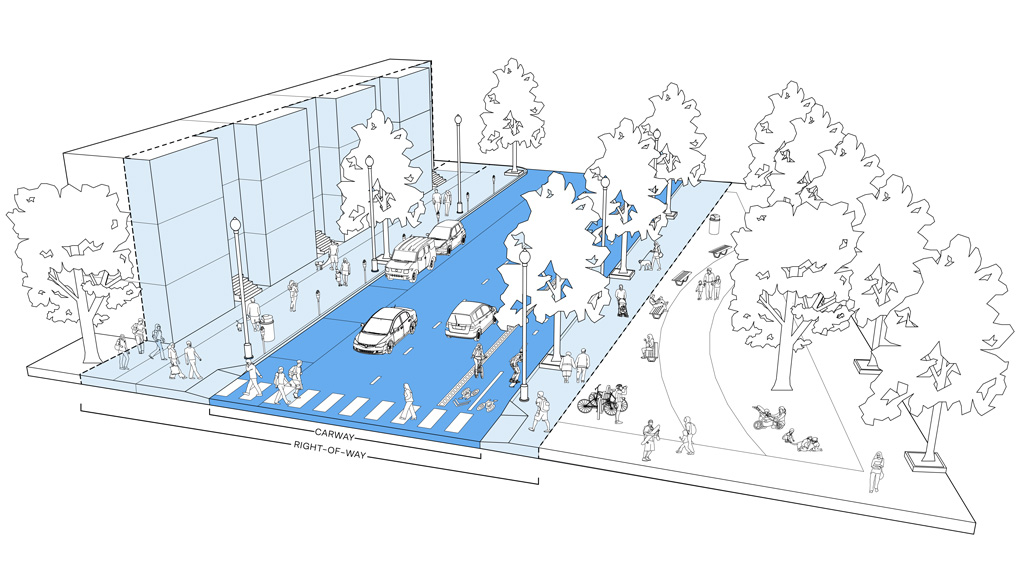

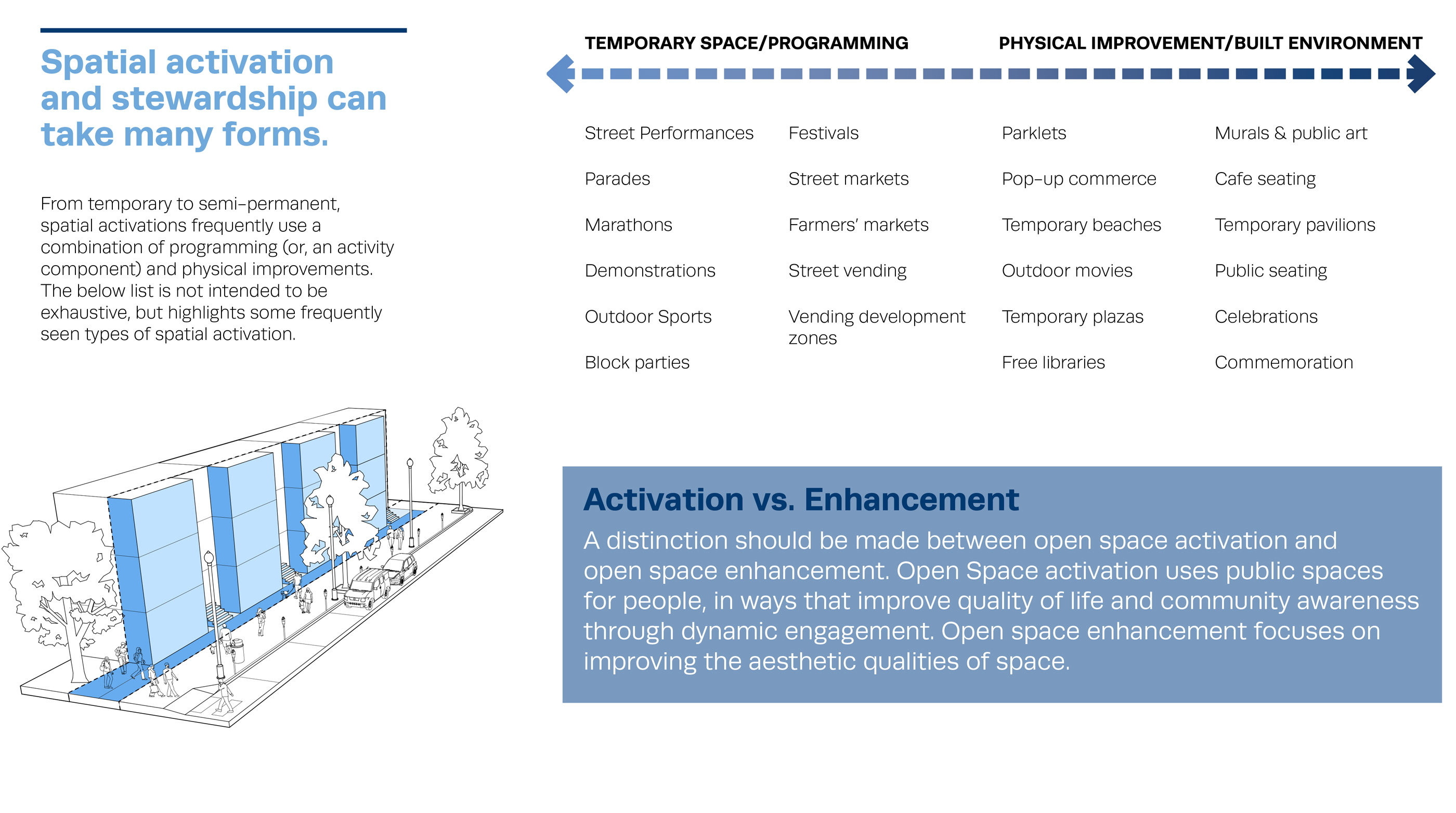

Pop-up pavilions, public art, street seating, parklets, outdoor beaches, seasonal theaters, farmers’ markets, festivals and street performances: these all are examples of space activation that we’ve come to expect in any thriving neighborhood. While these experiences have been parts of cities since their inception, more novel forms of space activation like outdoor yoga and coworking have recently joined the fray.

The rise of "pop-up" and temporary projects can be traced back to the 2008 recession, where stalled development sites and a surplus of underemployed designers turned the challenge of empty lots and storefronts into a more creative urban landscape ready to provide services and entrepreneurial opportunities. Today, these temporary and semi-permanent projects have evolved past being mere experiments. They now form a substantial part of urban business operations that governments and developers are championing, sometimes under the moniker of ‘placemaking.’ This is great news, but until recently, policies around temporary use of the urban realm have been murky and difficult to navigate.

In 2017, the DC Office of Planning (DCOP) engaged Gensler to write the DC Public Space Activation & Stewardship Guide, the city’s first comprehensive placemaking manual for citizens, community groups, business improvement districts, and developers. This guide, made possible through the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments Transportation Land-Use Connections Program, gives citizens and designers tools for activating and taking care of public space in their communities.

For citizens, developers, and municipalities, three main considerations stand out:

1. When it comes to placemaking, one size does not fit all.If you want to write your own placemaking guide, don’t copy and paste from another location. Gensler began writing the DC Guide by benchmarking similar guides, both domestically and internationally. In the U.S., only one other city (San Francisco) had undertaken an initiative on the same scale. Abroad, there were more examples set in a very different regulatory context. Some presented a very organized and analytical way of thinking about public space projects; others skewed to the creative side. Neither approach was right or wrong; both were specific to the desired outcomes and atmospheres of their respective locations.

We began by asking: what makes public space use in DC unique? For DC, it’s a combination of how public space is regulated across local and federal agencies; how the physical definition of the ‘urban realm’ reflects how the city developed over time; and how culture, tradition, and history are integrated. These three themes were uncovered via a series of workshops and interviews with the creators, consumers, and regulators of such projects.

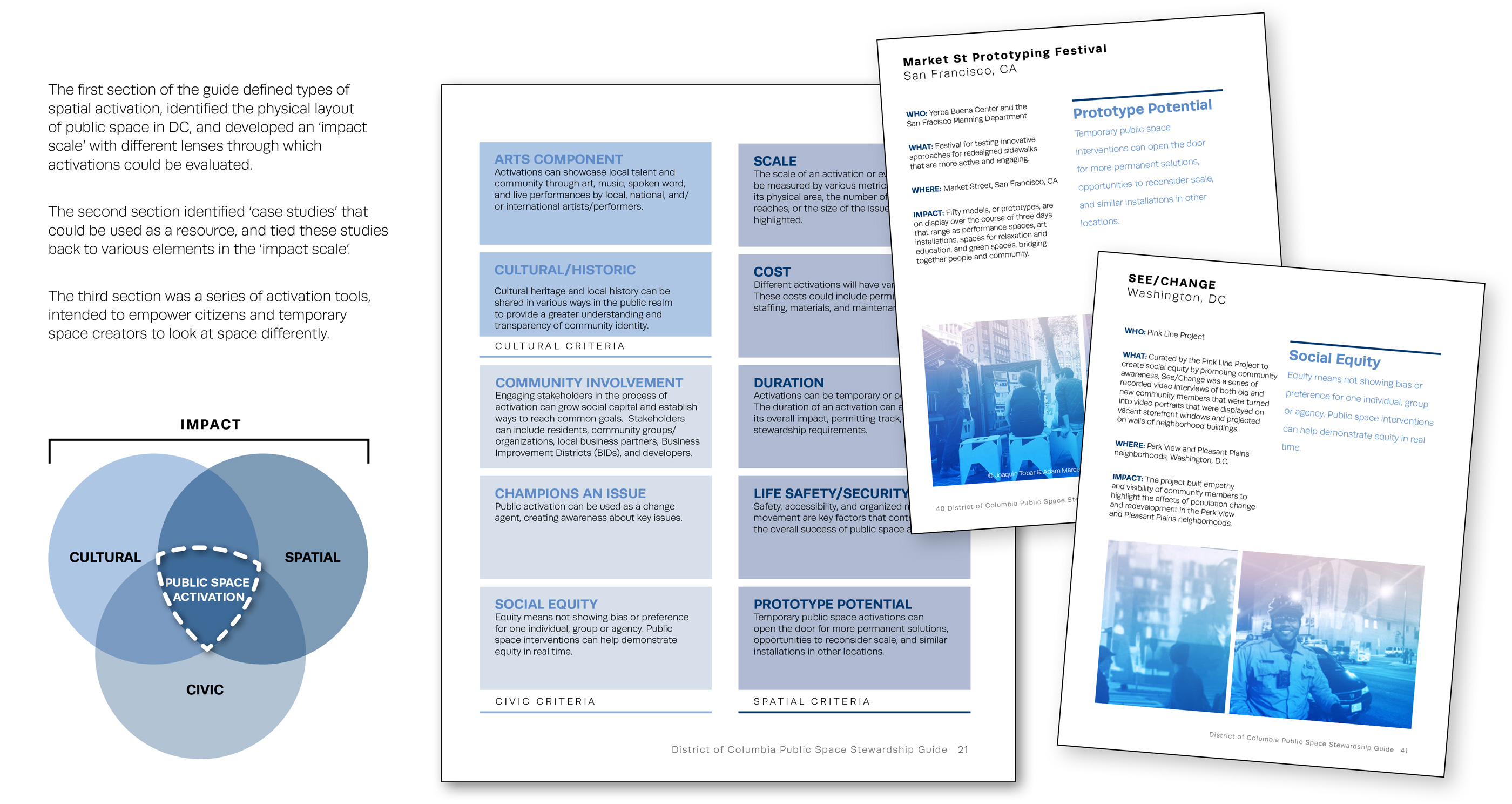

Space activation encompasses a wide variety of projects. A pop-up library and pop-up shop might be bucketed together, but their goals and outcomes are completely different. For the DC Guide, we developed an ‘impact’ matrix to help activators think about where they want to have the largest influence. These fell under three categories: cultural, civic, and spatial.

Cultural projects include those with an arts component or historic impact. For civic projects, activators are asked to think about the level of community involvement, the extent to which their project champions an issue, and social equity implications. Spatial criteria are slightly broader, with considerations of scale, cost, duration, security, and prototype potential. The idea is that every space activation project can’t hit homeruns in all categories, but it can meet targets if these factors are identified from the outset. For instance, the goals for the pop-up library might be community involvement and scalability, while the goals for the pop-up shop might be a high level of prototype potential for a more permanent future endeavor.

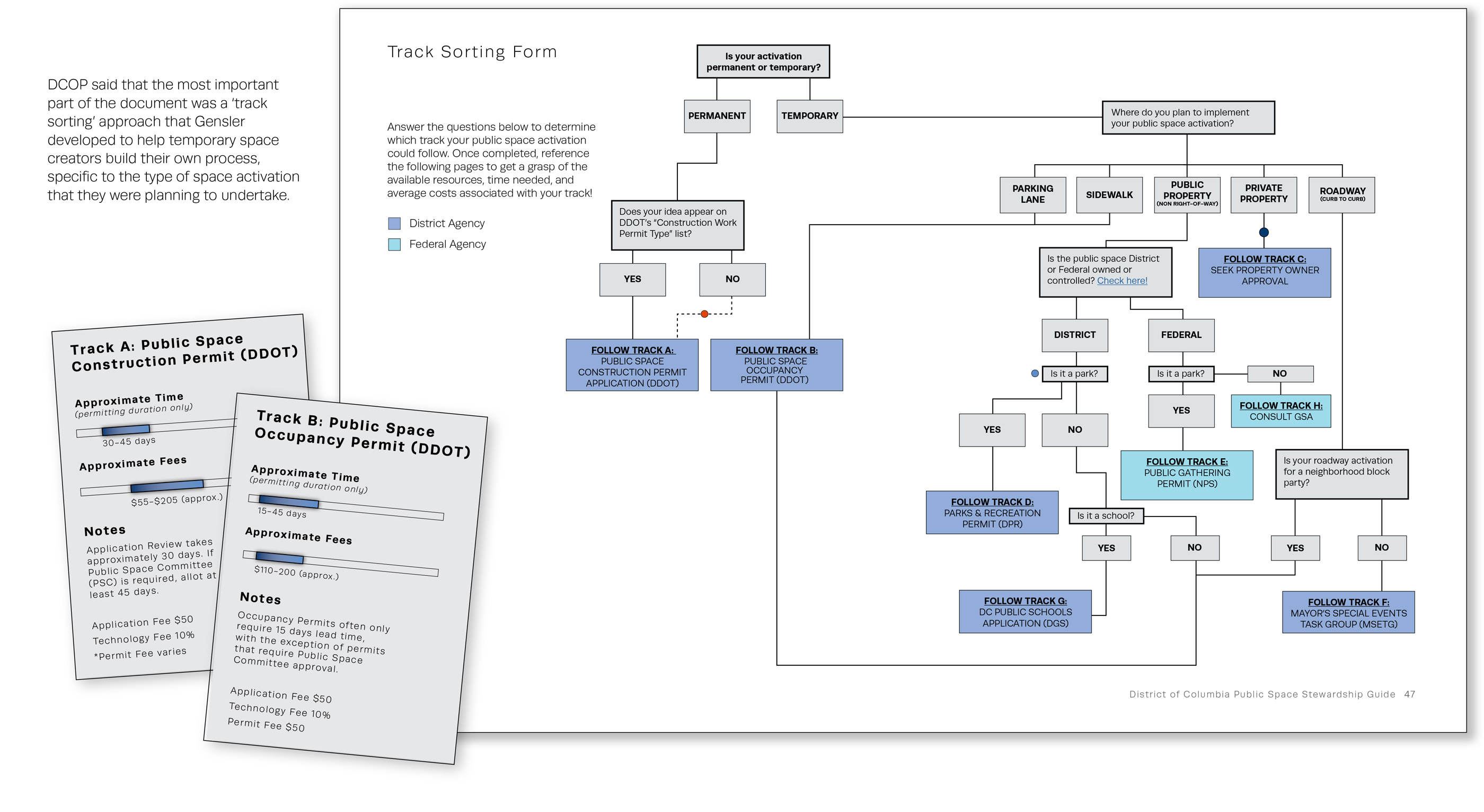

Many people think that space activation "just happens," but often organizing, building, and programming these events can take an army. It’s important to document events and installations — first, because they can be temporary, and second, because there’s the possibility to replicate them elsewhere. One of the DC Guide’s goals is to allow things already happening at a small level to scale up with minimum friction, while also adding transparency to the permitting and regulating process. In the guide, this was outlined through a "Track Sorting Form" that provides a clear pathway for stakeholders undertaking a variety of project types.

Space activation is a big part of what makes our urban environments exciting and vibrant. It invites participation from designers and non-designers alike. As citizens, it allows us to participate in the process of "citymaking," either passively or through active participation in planning and execution. Tools like the DC Public Space Activation & Stewardship Guide make our cities better-connected, so we call on our fellow designers and urban dwellers to use them, help draft them, and get involved.

The District of Columbia Public Space Activation and Stewardship Guide is available for download from the DC Office of Planning.