Fueled by the exponential growth of data, the urban jungles of yesteryear are turning into the smart and connected cities of tomorrow. Advances in sensor technology, cloud computing, bandwidth, storage, and other technologies are poised to improve people’s lives in exciting new ways.

Buildings have the capacity to monitor air quality, temperature, and energy consumption. Sensors can automatically close window shades on sunny afternoons or turn off the lights when a meeting room is empty. The question is, how do these operational technologies improve people’s experience at work?

That’s one of the queries driving an expansion of our workplace design practice to include intelligent placemaking. Designing an intelligent workplace, for example, requires an in-depth understanding of how workers use a space. Only then are we able to integrate data, artificial intelligence, and other intelligent building systems to empower people to do their best work.

Our goal is to create the kinds of workplaces that mimic the people who use them — places that are social, collaborative, self-organizing, flexible, tech-savvy, and reliant on data.

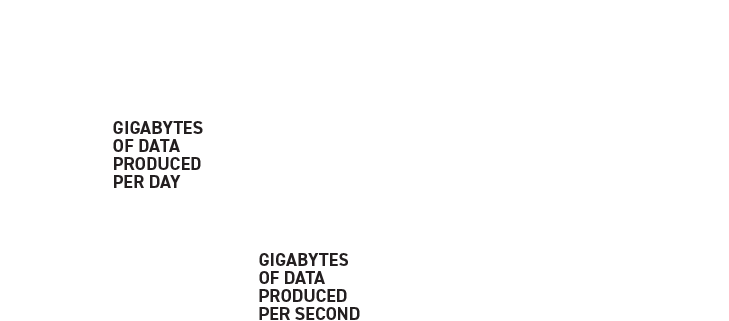

THE EXPONENTIAL GROWTH OF DATA

We live in a time of extraordinary innovation, driven by the exponential growth of data. In 1992, data was being produced at a rate of 100 GB per day. By 2018, that rate had skyrocketed to 50,000 GB per second.

IT ALL STARTS WITH DATA

Reaching our goal starts with data. Data helps us understand a web of relationships — how people, places, and things complement or detract from each other. Data comes from many direct sources, from sensors, mobile apps, and micro-surveys to communications network activity and badge swipes. It can also come from indirect data sources like health incident patterns, transportation analytics, and weather reports.

We entered this arena by piloting the integration of IoT sensor information into an evidence-based design process using Gensler’s New York office as a case study. We outfitted one floor with 1,500 sensors connected to lighting and electrical outlets, creating a network that tracks daylight levels, occupancy, temperature, and energy consumption.

One thing this research helped us understand is the ways technology can enable an integrated approach to designing for human engagement. Now designers are thinking beyond the desk, conference room, and call booth, focusing more on the dynamic connections that link spaces, people, experience, and work performance. Our attention is shifting toward the ideal of intelligent places that learn and adapt: fit-for-purpose, flexible spaces that activate productive work.

TEST AND LEARN

While it’s true that technology is driving advances in workplace experience, it takes more than technology to conjure up design solutions — it requires an appetite for continuous learning and prototyping.

Let’s say a company wants to move away from assigned seating for its employees in favor of dynamic seating, where workers use any available desk when they come into the office. To test the outcome, we create an experiment and assess the results. It’s a constant “test and learn” cycle. By collecting and analyzing data, we can determine: How did the new way of assigning desks alter the dynamic of the space? How did it impact productivity? Did it improve collaboration? Did workers have a positive experience? What was the impact on real estate costs?

This simple example, multiplied across a large organization with a global real estate portfolio, can deliver multilayered insights into how companies can plan and manage their workplace. Based on an agreed-upon vision, we work with clients to design the intelligent services required to realize that vision; we establish the metrics that will be used to measure progress; and we identify when to pilot, test, and learn. The cycle repeats, making adjustments each time. As we develop new insights, we can tune office spaces to support people’s most productive behaviors.

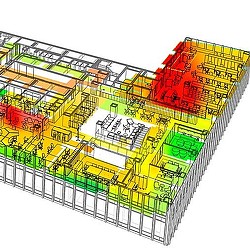

THE ADVENT OF THE DIGITAL TWIN

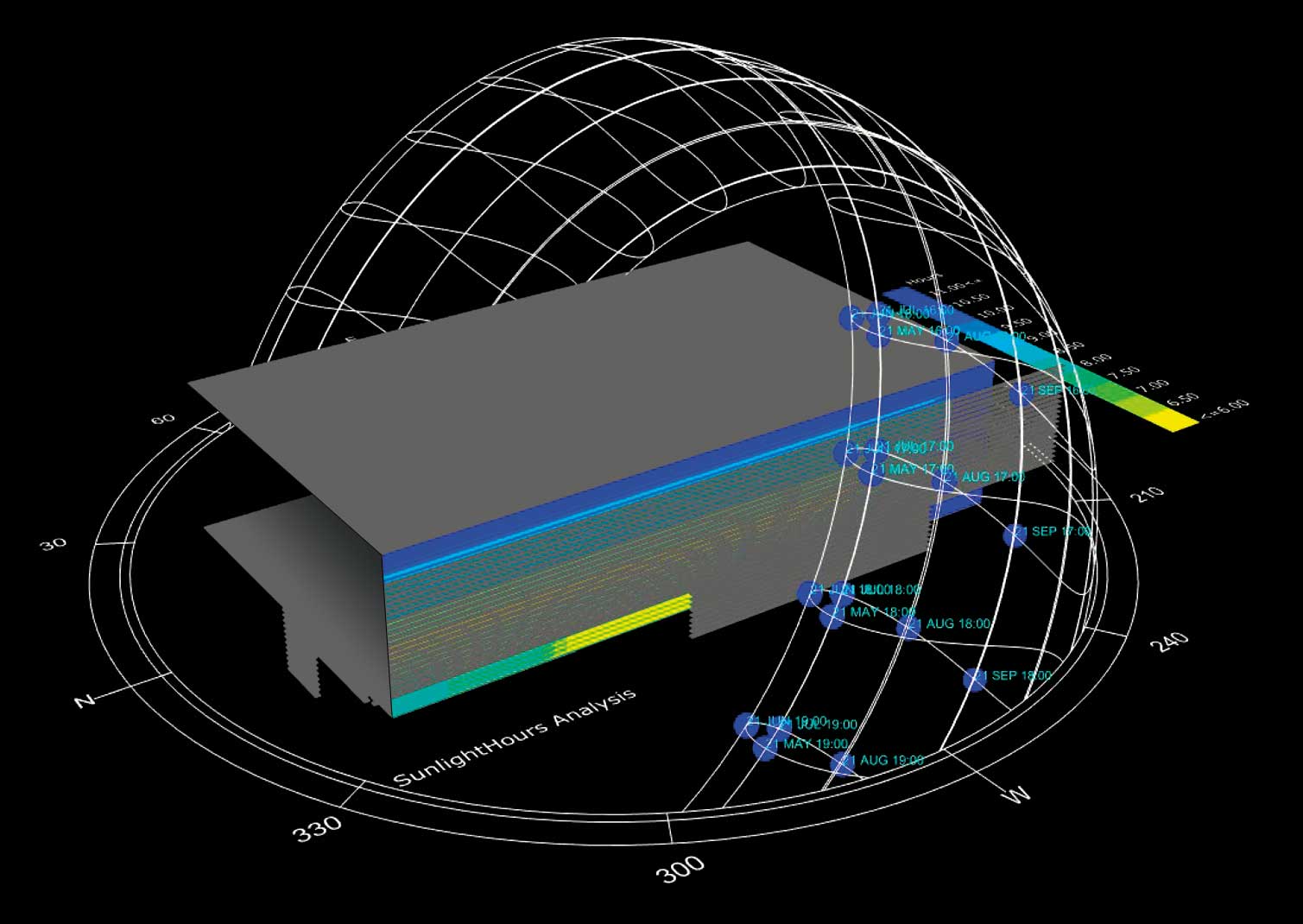

As intelligent networks get faster and smarter, more buildings will have a “digital twin,” a virtual copy reflecting what’s happening in and around them. This computational design analysis of Shaw Create Centre illustrates the profound advances in visualization, modeling, and simulation that are driving this change.

DESIGNING FOR FEEDBACK

In the end, designing an intelligent workplace is really the design of useful, real-time feedback about the things that matter most to occupants, managers, and business owners. This feedback empowers many parts of an organization — from facilities and AV to engineering and IT — while informing them on a wide range of issues. What is our sustainable impact? How does experience affect productivity? What is the best place for my meeting? Where can I concentrate? How many people can the building expect on Friday?

Every building can contribute to a city’s collective “smartness,” but instead of focusing narrowly on designing buildings that are digitally advanced, we should strive to create buildings that are agile for people.

That means collecting a variety of data that documents human activity and environmental factors that impact people’s performance, committing to a cyclical pattern of testing and learning, and leveraging that in-depth understanding to design solutions that help people perform their best.