Under the Hood: Office Buildings and Headquarters

The pressures that drive workplace change, especially the need to accommodate more people in less space, have a direct impact on the buildings and campuses that house the workforce. We asked a panel of Gensler experts what’s new and what’s next for these important project types.

What’s driving change and how are office buildings responding?

Hao Ko: There’s a real urgency to transform the organization quickly—“innovate or die,” as the saying goes, and innovation is a team effort. Technology is embedded now, and it’s changing how people work and how they communicate. The tech sector’s scrum mentality—hugely collaborative workspace to draw out the best ideas—has led one of our Silicon Valley clients to embrace horizontality: 5,000 people on two floors, which means floor plates of 250,000 square feet.

Of course, there’s still a place for verticality, in part because young workers like the city. But organizations don’t want to compromise vertical movement. The Tower at PNC Plaza in Pittsburgh, for example, will have a series of two-story atria that function as shared collaboration spaces and turn pairs of 22,000-square-foot office floors into contiguous vertical neighborhoods.

Benjy Ward: Two floors that aren’t connected is death to interaction. Even multi-tenant office buildings are looking at strategies to link floors, sometimes with external stairs. We also have a client eyeing former factories—a one-story, 340,000-square-foot building with a 23-foot-high ceiling, for example. They want people to mix and share ideas. This has room for mezzanines and bleacher seating for everything from team scrums to department meetings—with skylights to bring the daylight in.

Duncan Swinhoe: Another driver is how cities themselves are places of work—the activity isn’t confined to work’s traditional settings. So while urban office workspace is getting denser, businesses are also looking at places beyond their buildings as bona fide work settings. And they’re clustering in the neighborhoods where the talent is. In the process, they’re uncoupling from rigid design standards, opting instead to repurpose older buildings to get in faster. In the UK, the Class A standards set by the British Council of Offices are not always relevant. Today, businesses want their buildings to support rapid change and help them attract the talent demographic they’re seeking. They see the building, the business, and the location as mutually dependent, and their choice of buildings reflects that convergence.

If the old paradigm of an office building or a headquarters was processing tasks, like a factory, the new paradigm is unlocking people’s creative potential, like a university. That’s a big shift. It’s not about fixing space to suit efficiencies and desk ratios, but creating flexibility around where and when people do their work, both inside and outside of the building.

Are you seeing an emerging “new normal” in office building design?

Michael White: While standard practice varies regionally, we’re seeing a shift from center-core buildings with a multi-tenant loop to offset-core buildings that provide larger, uninterrupted office floors that tenants can modify in unpredictable ways. The media and tech sectors especially don’t want the core to inhibit their flexibility.

Large, even mega-large, office campuses aren’t new, but the desire for them in media and tech is for everyone to share ideas and see what others are doing. It’s all about proximity and osmosis. At the same time, you can’t just throw people together in these huge spaces. You have to be able to give them places that are scaled for humans.

A study we did recently with Hulu showed that once you get beyond 55 or 60 people in an open work environment, the sense of community goes out the window and noise becomes a problem. Hulu’s teams are large, so 55 or 60 is a good size for them. Tech-firm teams are often smaller. Giving a team a room of its own keeps it connected, but with acoustical privacy and separation. “My noise is good, yours is bad” is what I call this strategy: It’s only distracting to overhear conversations that aren’t relevant to your own work.

Duncan Swinhoe: Office real estate costs in the key European cities are very high. When this leads to exclusively open office floors that are very dense, productivity suffers. Office buildings should support how people actually spend their time. They need a diversity of other activity-based spaces to complement the open space, but openness plays hugely into visibility and culture. Objections to open plan ignore the importance of openness to creating human connection—an awareness of what’s happening and who’s doing what. Don’t forget that whole generations of the workforce have no experience of a private office—it’s an alien concept to them.

Hao Ko: If you create a work environment that improves people’s productivity and satisfaction, that can make a big difference to the organization. The Tower at PNC Plaza combines active and passive ventilation in a way that lets people control their immediate surroundings so they’re comfortable and productive. On a nice day, the double-skin façade lets them open a window or a sliding door to let in fresh air. It’s a no-brainer, but PNC is actually setting a new benchmark for headquarters office towers in the US market.

What’s happening with the technical performance of office buildings?

Robert Jernigan: The need for higher utilization that drives workplace design has a direct effect on buildings. When you triple the density, everything gets overloaded. The challenge is to meet the demand without adding to the carbon load. Technological innovations can help. Dynamic, computer-driven façades are an example. Elevators that know where you’re going and can optimize the process are another. Not only do they save time and energy, but they serve the building with fewer elevators, adding to its rentable floor area. We still design buildings and systems for peak loads instead of finding ways to spread those loads to the off-peak. Mixed use that shares systems and supports is one way to do this.

David Epstein: The focus is on creating sustainable environments in which work is pleasurable. In this era, everyone in the office is looking at some kind of screen, so the building envelope should be energy-efficient while it also controls brightness from the sun. We use software to identify and mitigate hotspots and balance daylight with thermal performance. The façades typically consist of unitized panels of aluminum with high-performance glass and shading devices. There’s a constant flow of new, higher-performing glass types, but it still comes down to making design choices. We make them quantitatively, testing digital and fabricated models, including full-scale façade mock-ups.

Helen Kuo: Achieving an ideal building environment requires a synergized approach to design and construction. Along with larger, better-performing façade systems, as David mentioned, we’re seeing more robust digital design tools becoming available that can handle today’s complex building shapes. We work closely with manufacturers to understand and exploit the potential of these different prefabricated systems. Now being tested, for example, are transparent glass panels that integrate photovoltaic cells. This ongoing dialogue informs our vision of the building, and then lets us bring it to reality.

Ben Tranel: Some companies pull real-time data out of their existing buildings to make them operate much more efficiently and intelligently. With new office buildings, you can plan this in advance, creating even more data points and giving the building a “brain,” a control system that gives the building operator constant feedback on its performance. Some US cities now require building owners to disclose their actual operating metrics. This should be a complete game changer in terms of validating building performance reports.

Are there any specific features you’re seeing that support today’s workforce?

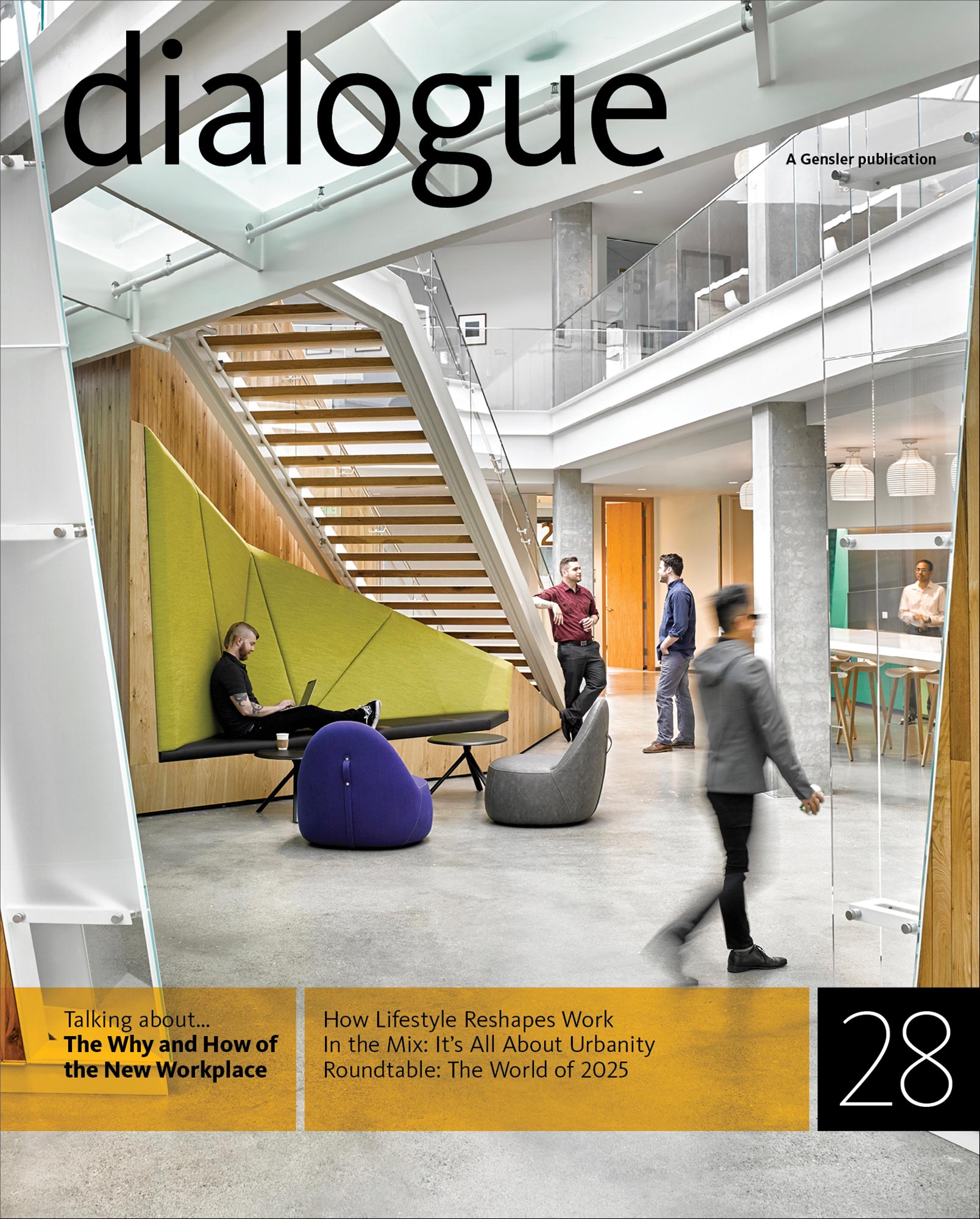

Joseph Brancato: Headquarters are supersizing amenities to reinforce brand and culture. They’re grouped so that everyone—employees and visitors—sees them first. They are constantly in use, with everything doing triple duty in terms of the activities it supports. Headquarters connect people, so you find multistory “town squares” now where large numbers can congregate—and the community can use during off-hours.

Connection is especially crucial for global companies. They want their training centers and collaboration spaces to help forge the kinds of friendships that build loyalty and convey values to keep rising stars in the fold. Health and wellness is a growing part of this, with some companies adopting the Well Building Standard as an extension of LEED—measuring human sustainability, not just building performance. The talent wars are back, so quality in a holistic sense is a competitive advantage.

Russell Gilchrist: Air quality is a big issue in some East and South Asian cities, so the ability to deliver it as part of occupancy comfort is a desirable feature. It means paying more attention to building services—by bolstering filtration, for example. Smog also cuts into daylight, so we increase the floor-to-ceiling heights to maximize the natural light inside.

David Epstein: Giving the workplace an outdoor connection is important, even in taller buildings. We’re designing a 29-story office tower in Austin with a series of decks to promote outdoor activity. The anchor tenant is pet-friendly, so if you’re working on the 22nd floor with your dog, you can both use the deck. It’s definitely a 21st-century world.

Martin Pedersen writes from New Orleans for the New York Times, Architectural Record, and other publications.