From Environmental Racism to Climate Justice

July 29, 2020 | By Mallory Taub

Recent events related to longstanding systemic racism and the current pandemic have caused architects and designers to consider issues of social justice and equity in the built environment with greater commitment and urgency. The first step in this effort is to recognize and understand how climate change disproportionately impacts communities of color, especially in our cities. Coordinated design and policy solutions are necessary to combat this worsening public health threat.

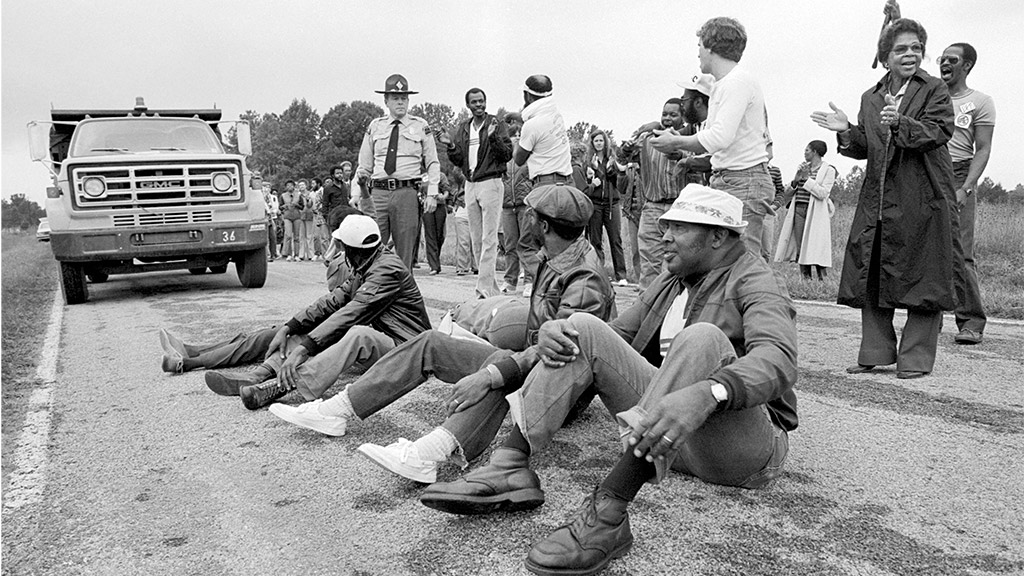

While the intersection of race and environmental impact has a long history, in the early 1980s national recognition emerged around what’s known as environmental racism — or the pattern of disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards experienced by people of color throughout urban, suburban, and rural communities. At this time, awareness grew after civil rights leaders such as Dr. Benjamin Chavis joined community members in protesting the dumping of harmful toxic waste in the low-income black community of Afton, North Carolina.

Over the 20 years that followed, awareness increased around the link between fossil fuels, unsustainable production processes, and climate change as the concept of climate justice simultaneously took hold at both global and local scales. The idea was to draw attention to the disparities in exposure to environmental hazards such as poor air and water qualities experienced by people of color – and do something about it. The Bali Principles of Climate Justice in 2002 specifically called these disparities out. More recently, the NAACP founded the Climate Justice Initiative in 2010.

Now, equity is a topic in all reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), with the latest report, “Global Warming of 1.5C”, stating that “climate change and climate variability worsen existing poverty and exacerbate inequalities, especially for those disadvantaged by gender, age, race, class, caste, indigeneity and (dis)ability issues of sustainable development (SD) and equity.”

As designers, we have a collective responsibility to address the threats of climate change in the built environment, while simultaneously promoting equity by working to protect our most severely impacted communities.

Here are three areas in which the work of architects and designers can deliberately shape the built environment to further climate justice:

According to a 2017 report by the NAACP and the Clean Air Task Force, Black Americans are exposed to 38% more polluted air than non-Latino white people and they are 75% more likely than the average American to live in fenceline communities — places bordering a polluting facility like a factory or refinery.

In fact, over 1 million Black people in the U.S. live within a half-mile of an oil and gas facility and are subject to potential health impacts from toxic air pollution and cancer risks that exceed levels of concern established by the Environmental Protection Agency. Many of these areas violate air quality standards for ozone smog.

As a result, asthma rates are relatively high in Black communities. According to the NAACP report, Black children suffer 138,000 asthma attacks and 101,000 lost school days each year as a result of ozone increases due to natural gas emissions during the summer. In 2014, Black people were almost three times more likely to die from asthma-related causes than the white population, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Services Office of Minority Health.

A 2008 study shows that even higher incomes do not insulate Black Americans from harmful pollution levels. Black households with annual incomes between $50,000 and $60,000 live in neighborhoods that are more polluted than the average white neighborhood, with incomes below $10,000.

To improve air quality, we can start looking at the estimated air quality impacts of different energy conservation measures during the design process. While it is common to look at the percentage of energy reduction of these measures, we can expand metrics that estimate their reduction on air quality and prioritize strategies that have the greatest savings for both air pollution and carbon.

We can also avoid combustion in the design of our heating, cooling, and cooking systems by using electricity rather than natural gas. Architects and designers can advocate for state building codes to require all electric buildings, particularly in jurisdictions that have made large commitments to clean electricity.

In Berkeley for example, the first building ordinance requiring all-electric consumption was established. Meanwhile in Brookline, a ban on new gas connections was implemented, and in New York state a commitment has been set to achieve 100% clean electricity by 2040.

Global warming is no longer a looming threat impacting our future climate: it’s a present-day killer. Today, extreme heat is one of the leading causes of weather-related deaths in the U.S. On average, extreme heat is the most fatal of all extreme weather events in New York City.

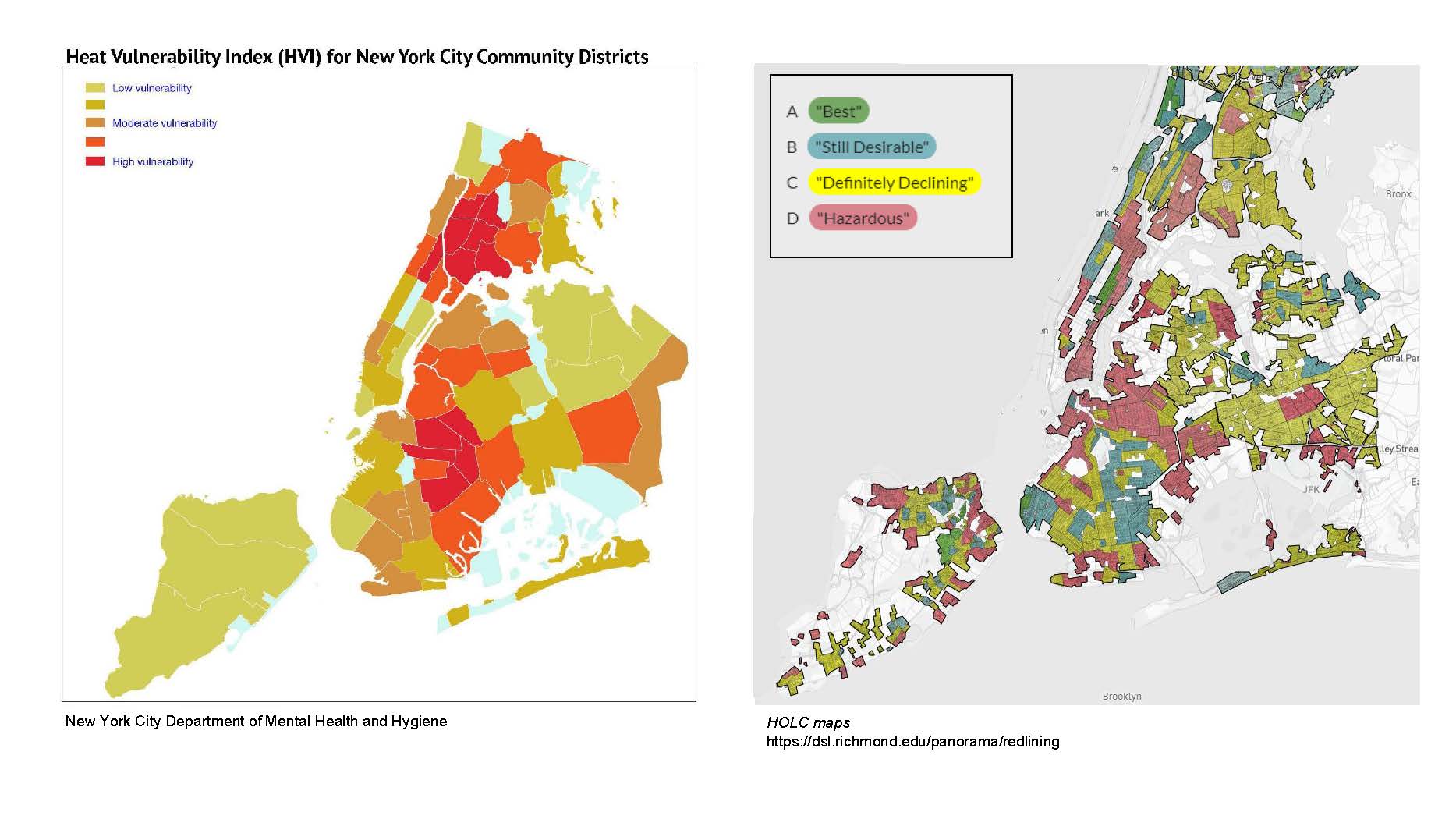

Extreme heat also disproportionately impacts communities of color. A look at New York City’s Heat Vulnerability Index shows that the neighborhoods that rank highest on the are low-income neighborhoods with residents who are predominantly people of color. Throughout the country, formerly redlined areas are consistently hotter than non-redlined areas, with land surface temperatures as much as 7°C hotter than adjacent non-redlined areas. Factors driving this risk at the neighborhood level include the distribution of vegetation, building typologies, surface materials, income, and health.

The Urban Design Forum recently released a report, “Turning the Heat,” which offers 30 distinct design, policy, financial, and community resiliency strategies to protect New Yorkers from the threat of extreme heat and rising temperatures due to climate change. Design strategies that can help address the issue include increasing insulation values and reducing leakage in building envelopes, designing exterior solar control devices tailed to the solar orientation of each façade, maximizing vegetation on roofs and throughout sites, using materials with high solar reflectance, and incorporating shaded exterior spaces.

Designers can also partner with community-based organizations to design low-carbon pop-up shade structures in heat vulnerable neighborhoods. These structures could be developed through a participatory design process that involves local stakeholders, and they could feature the artwork of local artists, and be used to host public arts and collaborative programs.

We can also initiate conversations with our mechanical engineering consultants about heat rejection to explore opportunities for heat recovery and encourage systems with lower heat recovery.

Finally, we can discuss cooling set-points in the summer with our clients to ensure we are not unnecessarily over-cooling our spaces since over 15% of heat in a heatwave is produced by air conditioning.

In June of 2020, the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE) published a fact sheet stating that, “historically, many marginalized groups have been underserved, overlooked, and underrepresented in local clean energy planning and policymaking.”

Policies that reduce high energy burdens and provide job opportunities for women and African Americans in the energy efficiency and clean energy workforce can provide economic opportunity and foster equity.

The environmental justice aspects of the California Senate Bill 535 legislation offer a good example. The law requires at least 25% of funds from the state’s cap-and-trade program in the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund be allocated to benefit disadvantaged communities, with at least 10% of the funds dedicated to projects within those communities.

New York City has also taken policy steps. In that city, over $10 million in grants was made available this summer to help underserved New Yorkers access clean, affordable, and reliable solar, representing the first step in implementing New York’s Social Energy Equity Framework.

Creating an inclusive, clean economy also involves creating access to jobs. Organizations like the South Bronx’s HOPE program are a good example. This group is focused on developing a local workforce trained in solar installation.

Design professionals can have a voice in advocating for addressing climate justice through policy, and the legislation mentioned above represent just a few of the different approaches to date. As designers, we can also partner with minority and women-owned businesses, and can consciously identify opportunities to bolster local economies when selecting or advising on consultant team and materials selection.

A call to actionThe issue of environmental racism is complex and dimensional — there’s no singular or easy solution, but as designers we can make a difference. We must understand and acknowledge that the carbon emissions from the built environment have consequences beyond contributing to climate change. And we must look for opportunities to directly and proactively address climate justice in our design work and make time to listen to community members about their most pressing challenges.

Everyone has a right to air that is clean and cool enough to breathe, regardless of skin color, zip code, or income. Fighting systemic racism at large requires working with renewed commitment to address environmental justice issues and the symptoms and causes of climate change, and this begins with our own projects and individual actions. From planning to urban design, we must have an inclusive design process that looks more holistically at strategic opportunities to create environmental and climate equity in all communities.

This piece originally appeared on Green Building & Design.

For media inquiries, email .