Design Ideas for the Post-Pandemic Public Library

July 28, 2020 | By Allison Marshall

Editor’s Note: This post is part of our ongoing exploration of how design is responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Public libraries in the U.S. have long served as welcoming and equitable settings for communities around the country. Residents can go to the library to learn, work, look for a job, and gain access to countless community tools and resources… until now. The ongoing coronavirus health crisis has interrupted these services, and it has challenged library administrators to rethink the library experience for residents as well as for library staff.

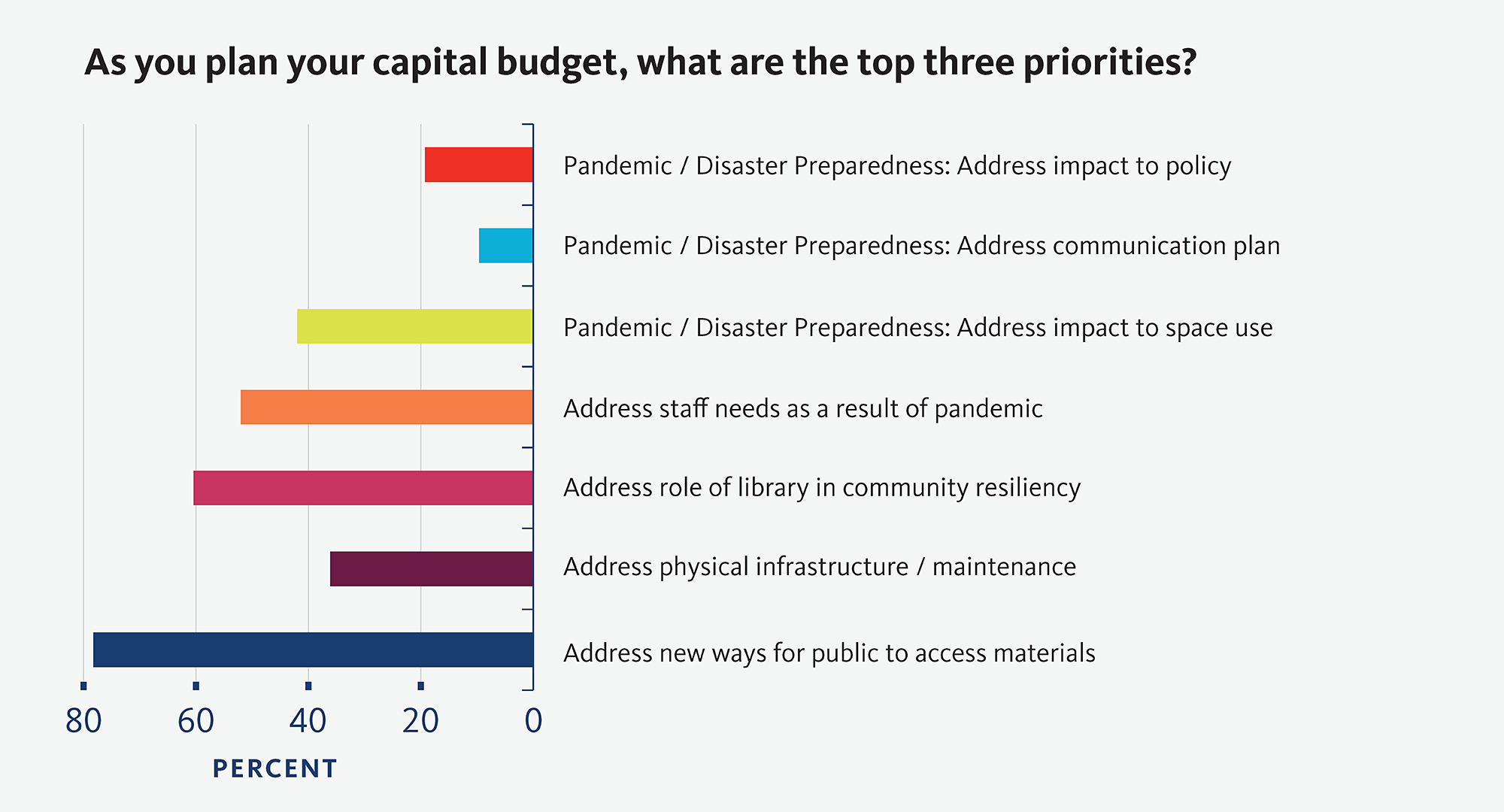

To get a better understanding of the pandemic’s impact on library operations, and to try to prioritize next steps, we collected over 200 responses to a survey of our clients and members within the American Library Association (ALA) community. We also hosted a virtual roundtable to talk to representatives who lead or operate 10 public libraries across the U.S. Both the survey questions and the roundtable discussion focused on the current challenges public libraries are facing and opportunities for long-term change in response to the pandemic.

Despite our limited sample size, the collective findings from the survey and the roundtable helped illustrate how we might rethink the public library and renew its purpose as an inviting and accessible community resource and meeting place.

Access to technology is a critical part of our lives – we use it to work and research, to do homework, to pay bills, to socialize and connect, to apply for jobs, and to get our news and health alerts, which is especially essential during the pandemic. For many, the public library is the only place they can get access to the Internet, which is why the pandemic has been so disruptive. The widespread stay-at-home orders cut off critical access for vulnerable populations across the country who lack access to computers or Wi-Fi at home.

According to our survey, 82% of respondents said that “technology access disparities” was a top priority issue impacting their library. We also know that simply having the latest broadband capabilities or digital tools and resources is not enough. Participants in the discussion regarded technology as a gateway to library resources and information.

To that end, is there a way to personalize digital experiences in public libraries? If the public library experience needs to adopt new safety measures and incorporate more touchless amenities and tools and fewer librarian-to-member interactions, how can technology be used to replicate or enhance the personal, human experience of libraries?

Over recent years, many library systems have already developed personal device apps — most of which allow users to browse digital collections or check the status of physical materials. But these apps could be further developed to grant patrons more access to resources and services as well. Likewise, existing interactive tools and games designed for children have allowed some libraries to migrate children’s story reading online — but there’s ample opportunity for these digital resources to become more robust and responsive to young readers’ evolving needs. A side effect, however, of expanding digital resources is the exacerbation of digital disparities, so in order to navigate a hybrid path forward post-pandemic, library leaders must partner with their communities, businesses, educational institutions, and city leaders to find holistic ways to promote more equity and equal access while humanizing both the virtual library “visit” and the reimagined on-site, low-touch, self-service experience.

Unfortunately, a side effect of expanding digital resources is the exacerbation of digital disparities. Simply adding new apps or digital tools is not a silver bullet. Library leaders must continue to partner with their communities, businesses, educational institutions, and city leaders to find holistic ways to promote more equity and equal access while humanizing both the virtual library “visit” and the reimagined on-site, low-touch, self-service experience.

Continue to Explore Touchless Library ExperiencesJust as library buildings themselves will need to change to accommodate social distancing and meet new health and wellness requirements, so too will we need to rethink the other physical parts of the library – the book stacks, archived papers, and media resources.

While a library visit is typically a hands-on experience that encourages guests to explore shelves of resources, facility leaders should think about incorporating touchless solutions at technology interfaces and consider how technology might be used to rethink the book check-out experience.

In addition, libraries increase the amount of wayfinding in the physical space, while also finding ways to govern the amount of people visiting. Library entryways could be decluttered via timed and pre-registered or ticketed visits, while more increase of self-service zones could limit interactions. More virtual programming combined with robust delivery and curbside pickup services could also be part of a more touchless library experience.

While there’s pressure to prepare for immediate needs during the pandemic, we’re also starting to look ahead to reimagine the future of libraries.

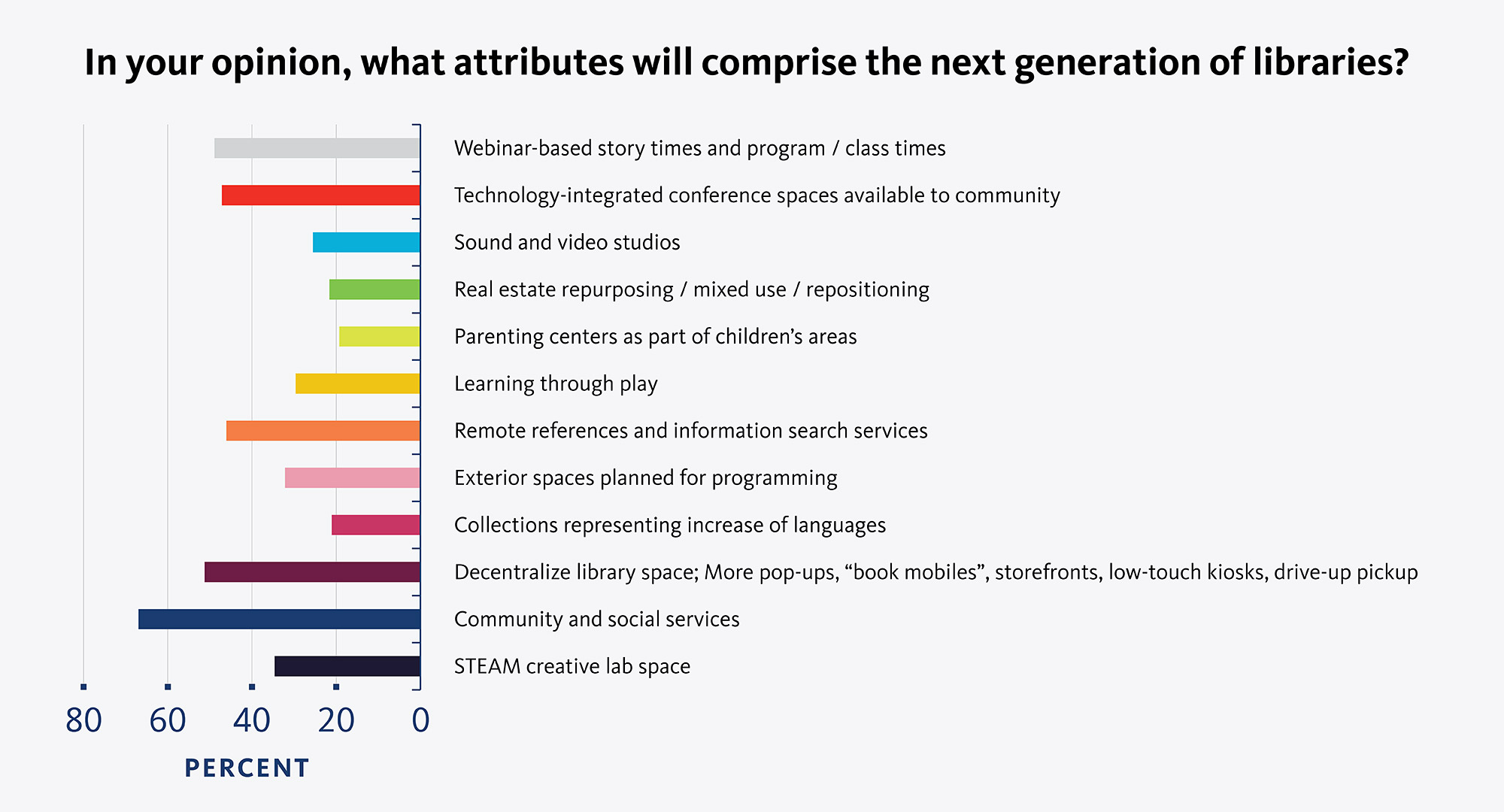

According to our survey, 65% of respondents believe that the next generation of libraries should focus more on community and social services — with particular attention on supporting those who don’t have ready internet access or are experiencing homelessness and need a comfortable, secure environment, even if just for a few hours.

As a first step, libraries could safely provide social services through teleconsulting. Already, many libraries across the country have social workers on-site to assist in providing much-needed resources, so a shift to virtual consulting could make sense, and actually provide more access to people in need.

Virtual learning opportunities could be expanded to include more English As A Second Language workshops, personal homework help, college admissions counseling, financial literacy courses, and other offerings that better address the needs of the public.

Secondly, libraries could consider becoming more decentralized. 53.7% of surveyed people believe that future library operations should expand to include pop-up locations, bookmobiles, bespoke storefronts, low-touch kiosks, and drive-up/pick-up options.

From a design and administrative perspective, decentralizing the physical library space is a long-term endeavor that will require significant planning for adapting and adding new services.

In the near-term, administrators can focus on small-scale, or “hyperlocal” approaches to swiftly launch new service models. In doing so, library leaders could quickly identify the needs of the specific communities or neighborhoods they know so well and cater resources to best meet their needs and make them feel welcomed.

Small-scale library services and infrastructure models could also quickly expand access for more people in local communities, compared to renovating or building large, regional libraries.

Regardless of the immediate or future changes required to modernize public libraries to meet the moment, one thing reigned true among all our survey and roundtable participants: communication is key.

It’s important to keep an open dialogue with the public and staff to let them know their civic leaders are actively researching and conceptualizing plans to diversify, digitize, innovate, and grow their updated service models. It’s also crucial to begin work on communications that address new protocols for cleanliness, capacity, and social distancing upon our return to the library.

Libraries can communicate new practices and standards through added universal signage and wayfinding, or they can adopt a more robust digital plan with email, a website, and social media.

Clear communication will increase transparency, continue engagement, and instill comfort and trust in both the public and staff.

Our survey and roundtable research reaffirmed that public libraries go beyond books, services, and devices. These institutions play a critical role within our communities, and they must evolve to meet new needs and lifestyles. They are deeply relational, foundational cornerstones to all members in the local society across generations.

This next chapter in the global health crisis can serve as a launching point for public libraries of all sizes to explore solutions that weave their space, enhanced technology, and local policies into a symbiotic community resource offering access and service for all.

For media inquiries, email .