The Rise of Second-Tier Cities

December 23, 2020 | By Sofia Song, Jon Gambrill, Whitley Wood

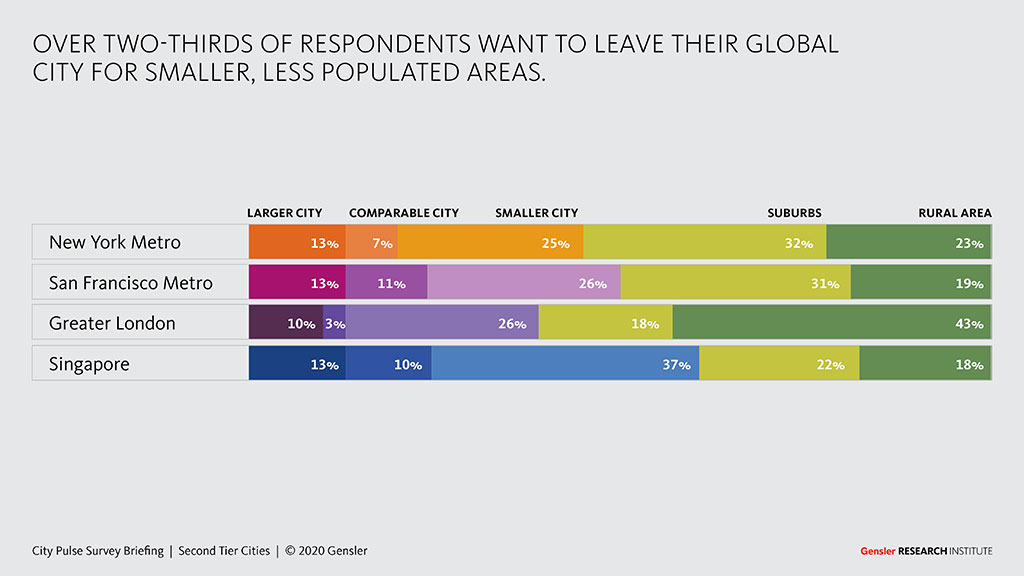

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered the landscape of our cities in just a matter of months. Second-tier cities (or “18 hour cities”) like Austin, Charlotte, Denver, and Raleigh, are booming as people who are no longer tethered to downtown offices or are seeking more value and space look to relocate from global cities like London, New York, and San Francisco to more affordable, less dense cities that still offer culture and diversity of a larger global hub, but at a smaller scale. The Gensler Research Institute’s City Pulse Survey, which surveyed residents of four global cities, confirms this finding: over two-thirds of respondents want to leave their global city for more low-cost, smaller cities that offer a high quality of life and lower cost of living.

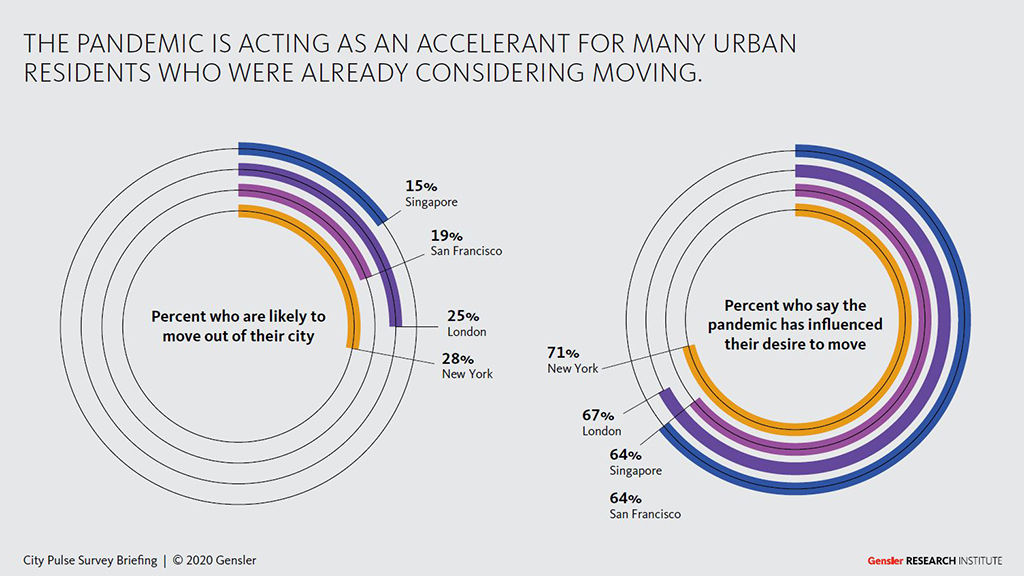

Our City Pulse Survey found that the pandemic was an accelerant in people’s desires to leave their global cities. One in four London and New York respondents were thinking of leaving their global cities. Of the people who said they wanted to move, many felt that the pandemic influenced their desire to move — as much as 71% in New York City.

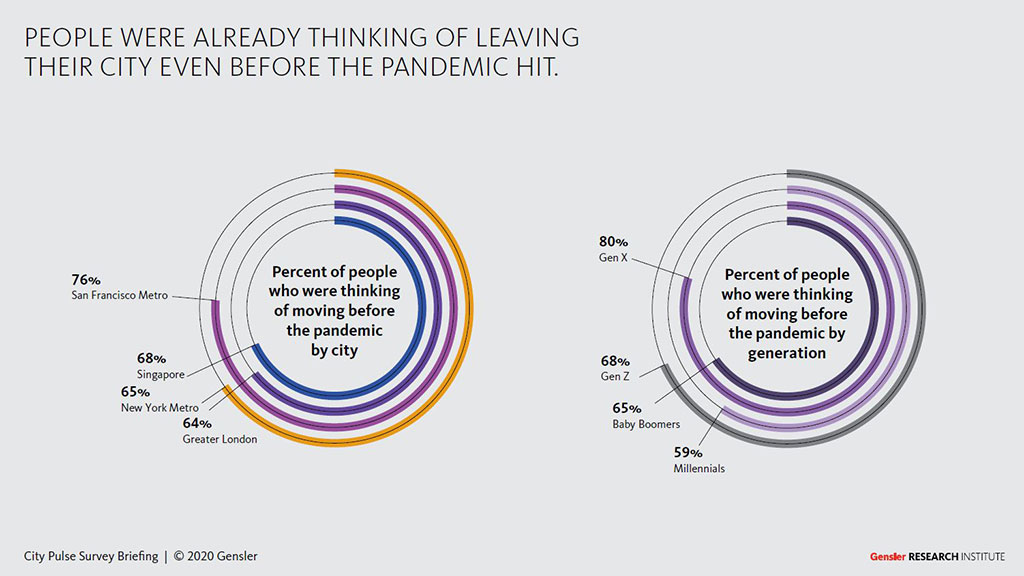

Yet, many respondents were already thinking of leaving their global cities even before the pandemic hit. In the case of San Francisco, 76% of respondents were already thinking of leaving their cities. Generationally, 80% of Gen Xers were already contemplating moves even before lockdown.

When asked where they wanted to move to, well over two-thirds of respondents wanted to move to smaller, less populated areas such as smaller cities, the suburbs, and even rural areas. Most notably, nearly half of London respondents wanted to move to rural areas while 60% of Singapore respondents wanted to remain in an urban environment.

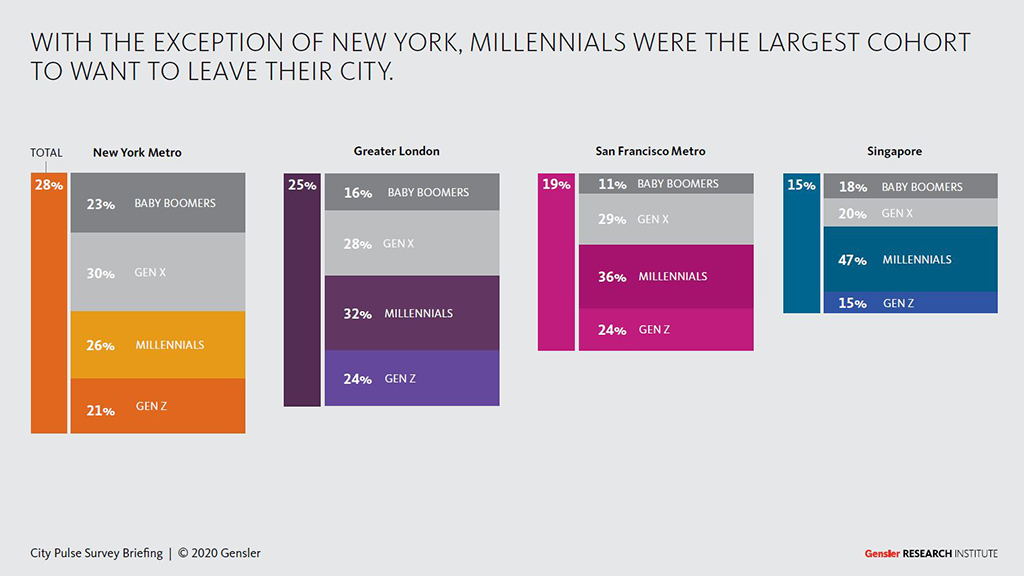

We wanted to know who wanted to leave their global cities. With the exception of New York, Millennials were the largest generational cohort to want to leave their cities. Nearly half of the people who wanted to leave Singapore were Millennials. So what is going on with Millennials?

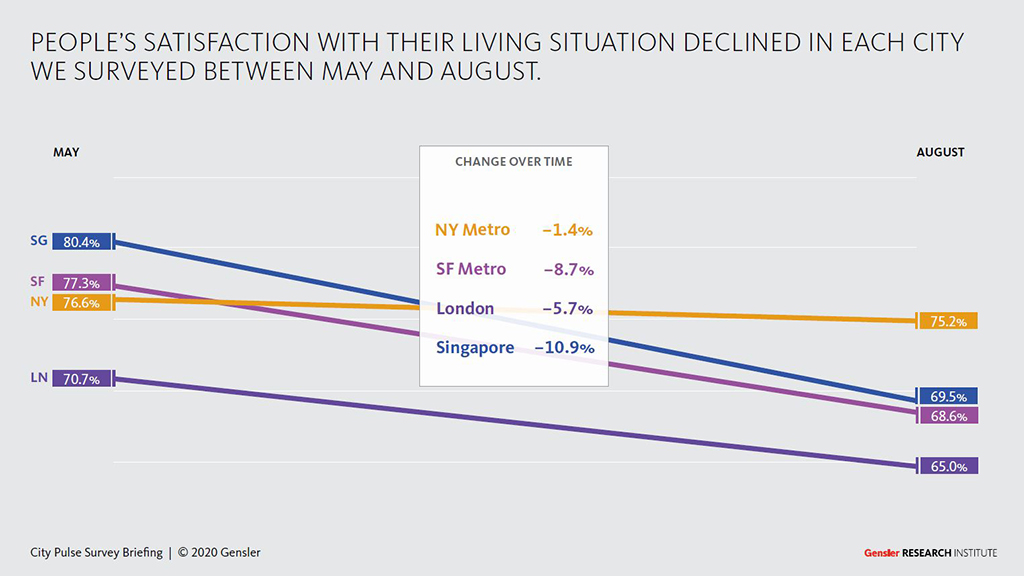

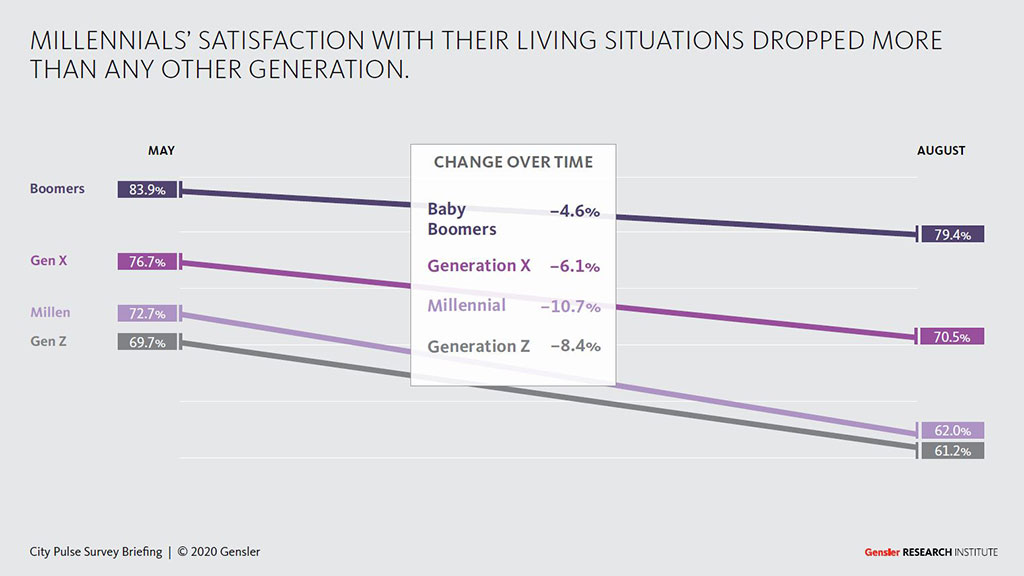

As the pandemic has gone on, we found that people’s satisfaction with their living situation declined in each city we surveyed. But we found that Millennials’ satisfaction dropped the most significantly.

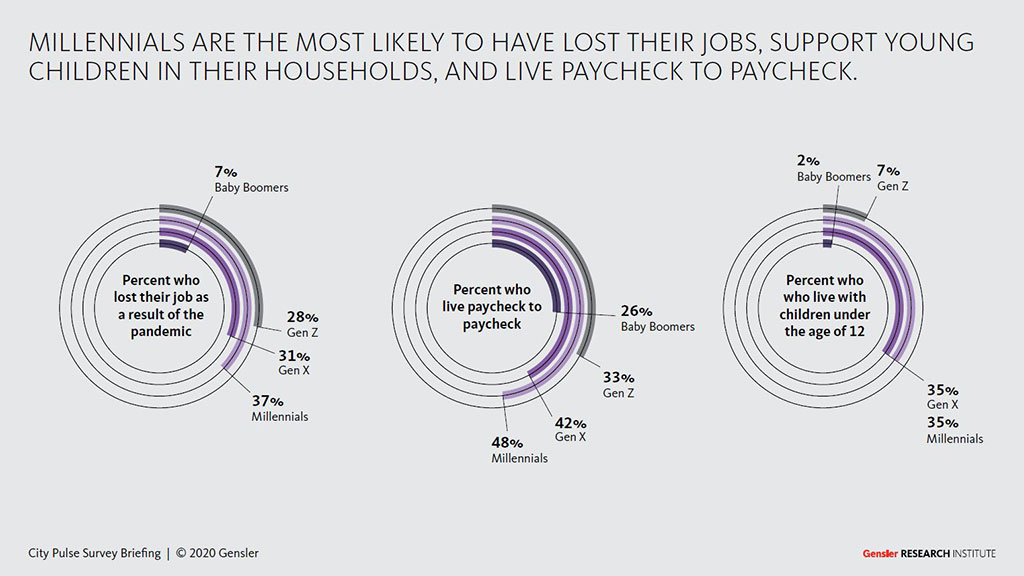

Based on our data, we found that Millennials were having the hardest time with the pandemic. They were the most likely to have lost their job directly due to the pandemic. They were most likely to be living paycheck to paycheck. And, along with Gen Xers, they were the most likely to be living with young children — the strongest indicator to lower levels of satisfaction with living situations.

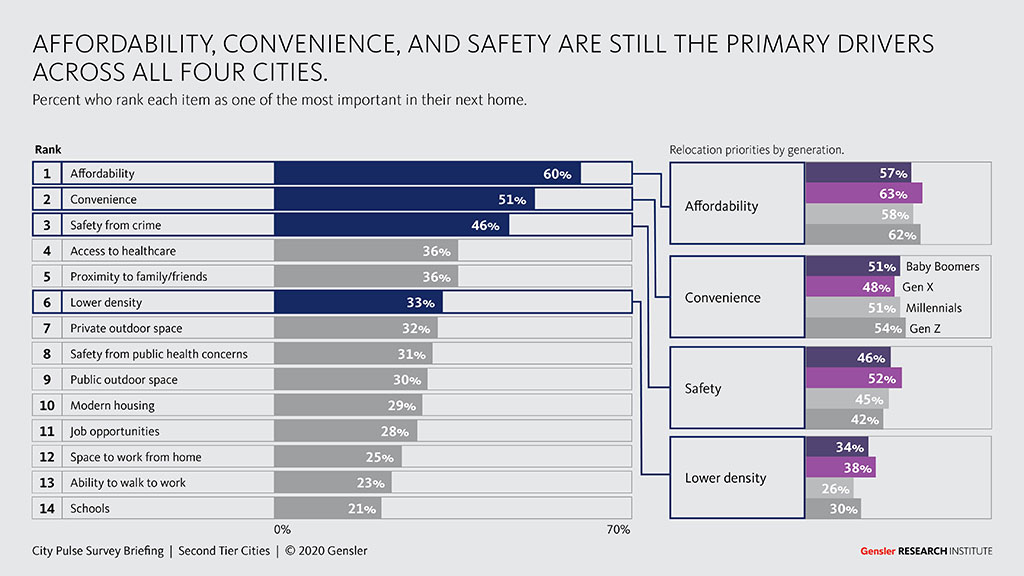

While the pandemic may have been an accelerant to people’s desires to leave these global cities, people’s primary drivers for moving remained the same; we found that affordability, convenience, and safety from crime were the top three drivers for respondents in all four cities.

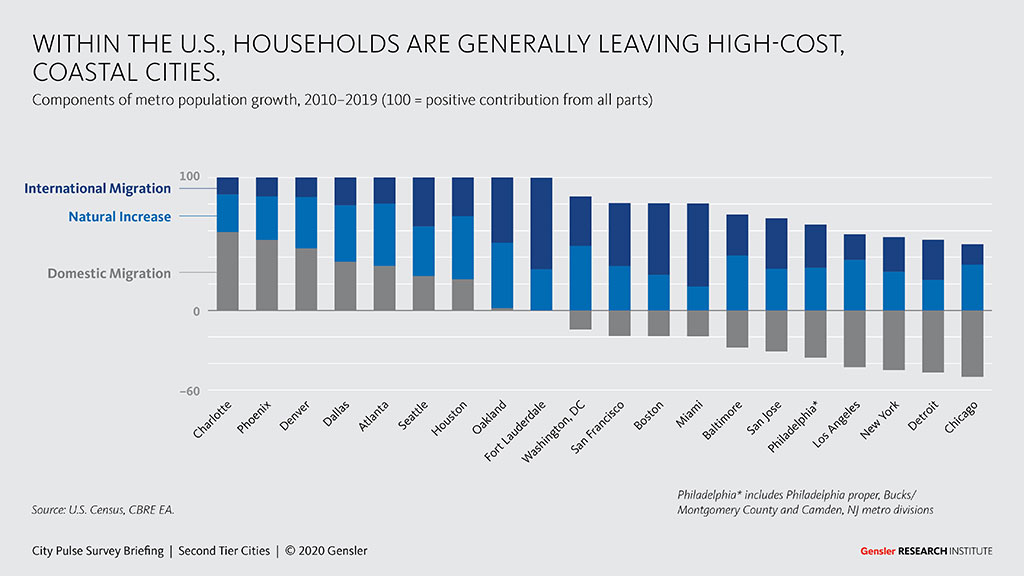

These findings are consistent with the population migration trends we have been witnessing over the last few years where people are leaving high-cost, large, global cities for lower-cost, smaller cities. (Credit: CBRE Econometric Advisors.)

Here are a few lessons that cities, developers, and building owners can take from this research to make second-tier cities more diverse, sustainable, and livable:

1. Get to know your city.It’s important to know what types of programs or initiatives your city is trying to advance. In Denver, for example, the City is supporting the Outdoor Downtown, a 20-year master plan to create vibrant outdoor spaces in Denver’s urban core through programs such as urban tree planting and improved access to public space. In our project work, Gensler is doing a lot of building repositioning work Downtown, so we can promote these programs and steer our clients to solutions that will not only upgrade the buildings, but also benefit the public realm in our downtown. In addition, we have linked our clients to the programs in the city that can offset costs of these renovations, such as a tree planting grant. This not only enhances public perception of the building or project, but it also has a bigger impact — it may be the right thing for the community.

2. Explore public-private partnerships.It’s also essential to understand the unique makeup of your city, its Central Business District (CBD), and what major businesses have the most influence so you can partner with them and understand what your city is planning. In Charlotte, for example, there are four prominent employers in the CBD, and they have the potential to make a difference in improving the Central Business District. Thinking about how the ground floor spaces can be leveraged to showcase the city, the focus needs to be on providing a rich diversity of businesses and spaces that serve the community at street level. Creating a pedestrian-friendly walkable city while enhancing the equity and diversity of spaces the public has access to in the Central Business Districts will enrich cities.

3. Small interventions can have a big impact.Architects and planners have long turned to tactical urbanism to make a big impact through small interventions. For example, during the pandemic, underutilized or abandoned parking lots have been converted into parklets for outdoor dining. Cities can gain traction by bringing stakeholders together to solve for a particular locale, which can lead to a more innovative path, such as a ground floor repositioning. Creating spaces that bring a community together and support small and diverse businesses will only enhance the fabric of the cities.

As more people migrate to second- and third-tier cities, we should look to opportunities to drive innovation, build arts and culture, create more equity and diversity, and embed the DNA of the city in its locale to make these places more vibrant, livable, and accessible for everyone.

For media inquiries, email .