The Pandemic’s Lasting Effect on Our Healthcare System

April 02, 2020 | By Scot Latimer

Editor’s Note: This post is part of our ongoing exploration of how design is responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

With the unfolding global pandemic, it’s difficult to remember that just a few short months ago we were grappling with the “normal” challenge of making change in a health system moving at a snail’s pace. Today, in contrast, we are seeing 48-hour hotel conversions and one-week hospital constructions. How can we leverage these challenging times for good?

Interestingly, lasting change in health care delivery has historically occurred in response to shocks to the system. The 1918 influenza pandemic, an event that killed over 50 million people worldwide, also led to discoveries of virus’ role in the spread of disease, vaccine development, and advances in public health and hospital design. It makes sense that we should speculate on some of the lasting changes we will see in our increasingly global system in the wake of today’s crisis.

One of the greatest revelations so far is that we have become complacent and one-dimensional in our planning. In the last decade, we have obsessed about refining and wringing efficiencies from the normal, which has actually narrowed the range of options we consider as a result. Planning for the norm has left us ill-prepared for a crisis.

And yet, we also know that it’s irresponsible and expensive to plan for outliers. When we get through this crisis we won’t return to business as usual. How should we think about extremes? What should we consider as the new normal?

Planning should be about exploring the unexpectedDuring the outbreak of SARS in 2005, health systems were mobilized to understand and prepare for community response as a system. Beds (especially ICU and isolation beds) in any given market were inventoried as resources to be shared in the community, and provisions were made for the transfer of patients among competitors.

Today’s planning efforts, by comparison, rarely utilize scenario planning or other techniques to hypothesize future outlier events and responses. Emphasis on the “triple aim” — the simultaneous pursuit of improving the patient experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of health care — has been well intentioned, but it has also had the effect of de-emphasizing the role of the hospital and limiting consideration of (high cost) acute system hubs. “Population health” has become synonymous with the movement of services out of the hospital and closer to a patient’s home in a coordinated system. This is a worthy concept, yet the COVID-19 pandemic makes clear that there will be times when managing population health requires a bellows-like hospital at the hub; one which can expand to provide more high acuity services and contract when the crisis is over.

Many experts and organizations have predicted future pandemics as a forgone conclusion, but pandemic is not the only outlier event health systems may face. Many countries live in the shadow of conflict, biological warfare, and threat of embargo, any of which would stress their health systems. Our planning and design processes need to be re-thought not just in terms of building connections among the elements, but of flexing accommodation of demand significantly in times of system stress.

Differentiate: Good investments, poor investments, societal investmentsWhat will be good investments in health infrastructure in the future? Investments that enable the system elements to change role and absorb shocks are clearly desirable, but not at the cost of building for the worst case. Health care has long been susceptible to “greatest common denominator” planning: if a 600-square-foot operating room is sufficient for today, then why not plan an 800-square-foot room for tomorrow, and maybe 1,000 square feet, just in case we have new technology in the future? The challenge is to separate the possible, however likely, from the irresponsible.

Clearly, the global health system will need to plan for increased capacity in times of crisis. While some have proposed we equip patient rooms with two headwalls in order to double capacity, this may provide inadequate isolation and prove an expensive solution for a once-in-a-decade need. A smarter solution may be, for example, to ready parking facilities or housing close to the hospital for rapid conversion in time of need. Proximity to the acute hub is the key. As the current health crisis is revealing, a shortage of medical professionals and-high tech equipment is a major concern, and close connection to the high-tech core is vital.

The bigger question we should be asking is: What is the role of any health system in a national crisis, particularly in countries like the United States where much of the infrastructure is private? Whose responsibility is it to fund our future readiness for a societal need? China was able to build a hospital in Wuhan in seven days because the country had invested in prefabricating and pre-positioning patient rooms for rapid response. The coronavirus crisis will no doubt raise more questions about government’s role and responsibilities (vs. that of the private sector) in accommodating a surge in demand.

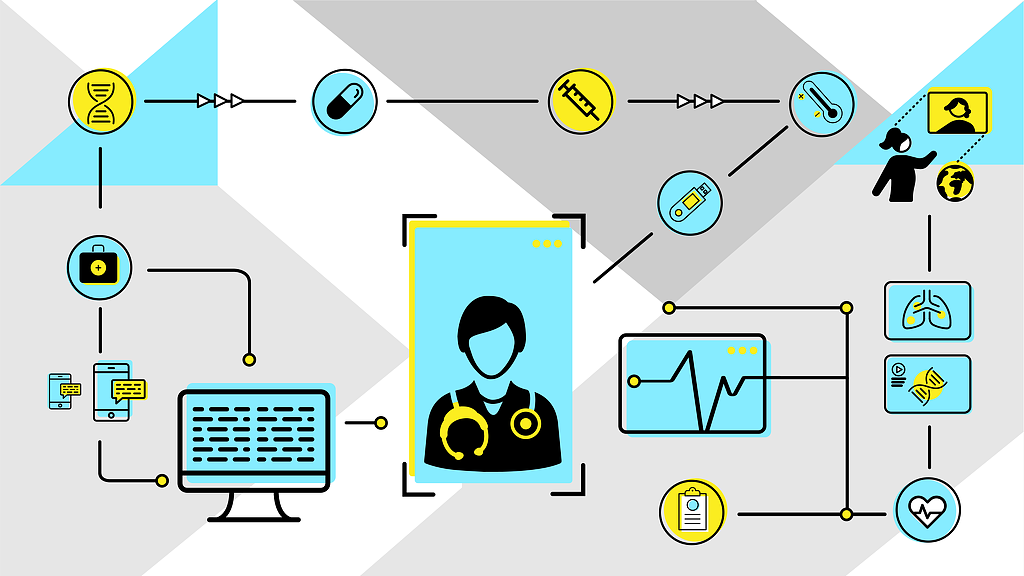

Solutions for a new normalRegardless of long-term outcomes, we can already see some changes underway that will form the foundation of the new normal. Take telemedicine. The United States has been among the slowest to adopt the practice of virtual diagnosis and consultation; not because of problems with the technology, but because of payor unwillingness to compensate providers for seeing patients virtually. Yet last week, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services struck down all those restrictions in order to permit remote consultations, allowing patients to receive a wider range of services without having to travel to a healthcare facility.

With telemedicine now entering the mainstream of U.S. healthcare, with medical professionals now being permitted to work across state lines, and other legacy restrictions being lifted, we can look for an unleashing of the innovation pent-up in the health system to integrate advancements in artificial intelligence and other new capabilities in the service of better, lower-cost care.

Imagine a medical office where physical and virtual visits are interspersed throughout the workday. That office will need less space to see patients physically, and different technology to see them virtually. Offices can become smaller, or space can be redeployed for community uses, for mental health uses, or to advance a wellness agenda.

What’s next?The future normal is already here. Widely distributed systems of care with hubs that can expand and contract, and virtual care which reaches into the home through telemedicine and wearable technologies, will revolutionize care delivery around the globe. By focusing on human need and experience we’ll transform healthcare institutions from places of illness to places of wellness, and health systems into conveners of a broad health and wellness agenda for our communities. In making this transition, we’ll soften the next shock — in whatever form it comes — because we’ll have planned the right system.

For any media inquiries, please email .