The Secret to Paris 2024’s Olympic Success? Reuse, Temporality, and Legacy

How an innovative, sustainable, and cleverly timed approach helped Paris avert the pitfalls many cities face when hosting the Olympic Games.

Widely praised as a success, the 2024 Paris Olympics has set a new architectural precedent in the organisation of large-scale sporting events by completely reenvisioning its urban interventions: through a savvy combination of long-lasting infrastructure investments and demountable temporary structures, Paris has managed to avert the many pitfalls cities face when hosting Olympic Games.

Amid concerns about rising costs, environmental impact, and unpredictable levels of public support, the Olympics have faced some challenges in recent years. In 2004, 11 cities competed to host the Summer Olympics. Twenty years later, after the withdrawals of Rome, Budapest, and Hamburg, the 2024 and 2028 Summer Olympics were jointly awarded to Paris and Los Angeles, with as many candidates as winners. Some speculated that the International Olympic Committee might eventually face a shortage of host cities.

For the Paris 2024 Committee, the question was therefore less about how to succeed at organising the Olympics, but rather how not to fail. Paris simply had to take a different approach. The committee’s strategy can be summarised in three principles: “reuse what you already have,” “only build what you really need” and “dispose of what you no longer need.”

“Reuse what you already have” – Existing infrastructure

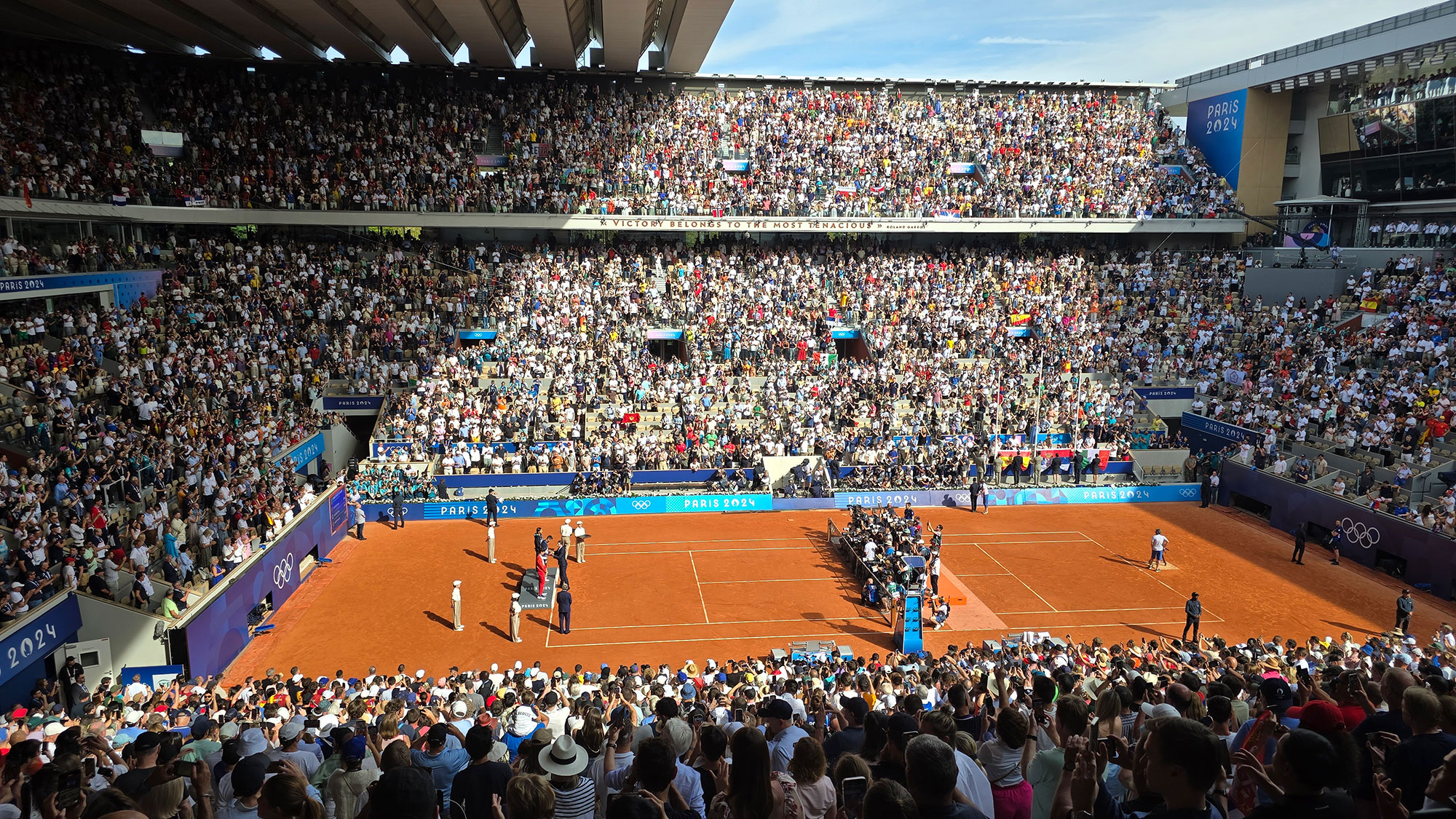

One of the main arguments put forward by the Paris 2024 candidacy was its commitment to maximising existing infrastructure, with 95% of the venues already in place. This approach significantly reduced costs, conserved resources, and minimised emissions. Within Paris and across different locations in France, the stadiums used for international sporting events in football, tennis, and other sports were all asked to host various Olympic competitions.

“Only build what you really need” – Infrastructure reuse

For the new infrastructure, the Paris 2024 committee prioritised future post-Olympics needs, ensuring that these projects would serve lasting purposes beyond the Games. This strategy aimed to create facilities with designs that effectively address the specific needs of their communities, ensuring long-term relevance and use.

In addition to a focus on the legacy of these infrastructure pieces, the Olympics also served as a formidable playing ground for the experimentation of new sustainable building techniques, with multipurpose, modular facilities using low-carbon materials and energy-efficient systems.

For example, the Olympic and Paralympic Village will be transformed into a range of private, student, and social housing, as well as offices and public spaces, expected to accommodate 6,000 residents and 6,000 workers. There will also be schools, parks, and improved transport links. These buildings are designed to meet Paris 2024’s ambitious sustainability targets, aiming to reduce the carbon footprint by half compared to London 2012 and Rio 2016, with a goal of limiting emissions to no more than 1.58 million metric tonnes of CO2.

The Aquatics Centre in Saint-Denis is the only competition venue built specifically to meet the Games’ requirements. In an area where half of the children cannot swim by the time they start middle school, the Paris 2024 project aims to leave a lasting sports legacy for Seine-Saint-Denis and its community.

An outstanding example of low-carbon construction, the building is supported by a concave timber roof frame that reduces the volume needing to be heated. The energy-efficient swimming pool is powered in part by a photovoltaic roof, covering about 20% of its electricity needs, while heat recovered from a neighbouring data center helps maintain the pool’s temperature.

The most important and long-term efforts in terms of coordinated infrastructure deliveries were not competition venues themselves but the networks of public transportation and sewers — the kind of renovation that only happens once in a century.

To bring the Seine’s water quality up to health standards and allow public swimming by the summer of 2025, a €1.4 billion renovation of Paris’ sewer system was undertaken. This project involved retrofitting the existing network and constructing two 50-meter-tall retention tanks to prevent wastewater from overflowing into the river during heavy rainfall.

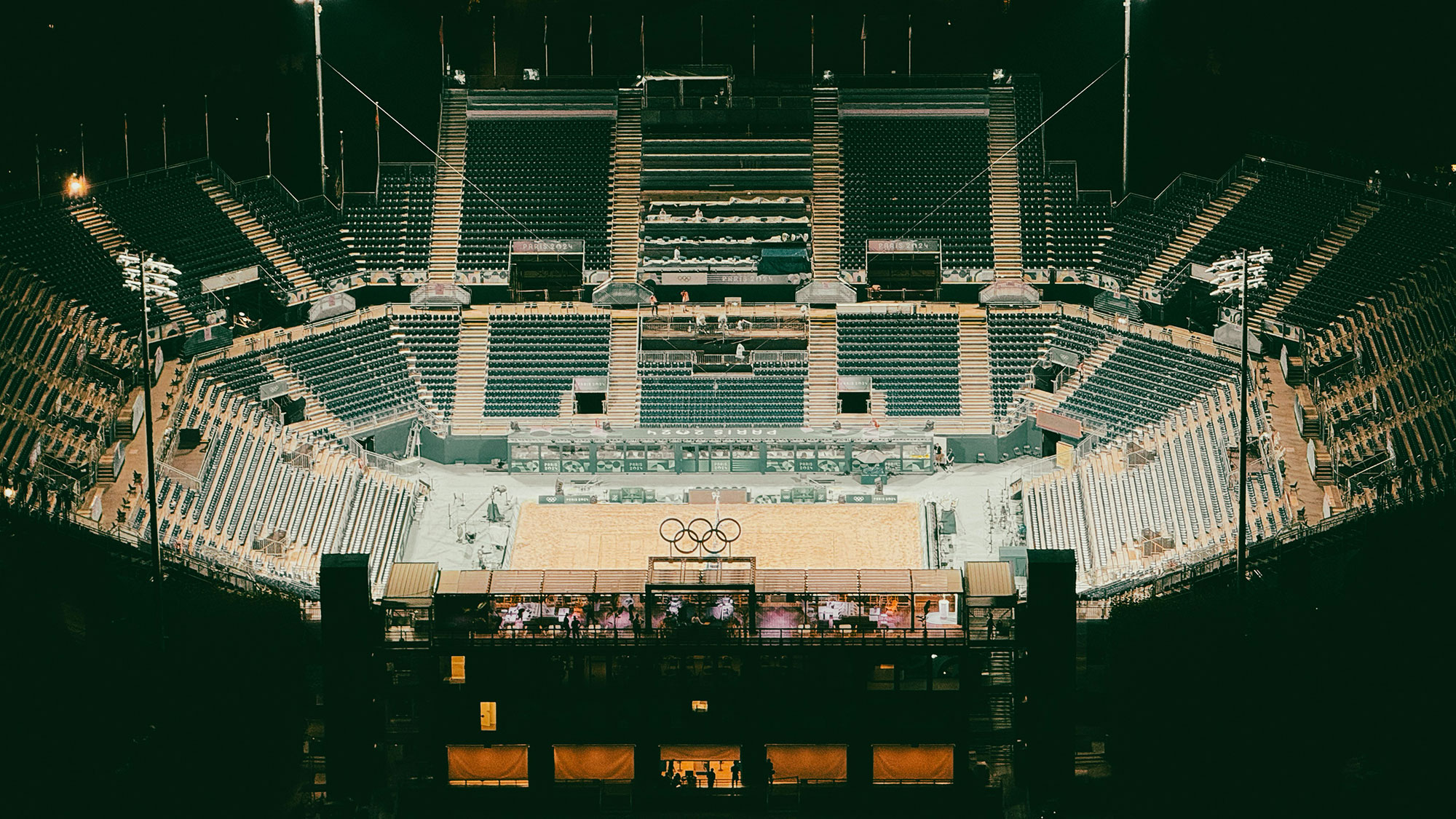

“Dispose of what you no longer need” – Temporary structures

The crux of the problem when it comes to delivering Olympic infrastructure is the mismatch of capacity during and after the Games, which often leads to underutilisation and urban decay of large sports venues.

Paris’ answer to this problem was to use tactical urbanism at scale. Instead of limiting competitions to be within stadiums and Olympic villages, the city decided to temporarily activate public space in the historical center, using low-quality and demountable structures as seating and recently renovated monuments as a backdrop.

This temporary activation strategy was complemented by an extensive, coordinated campaign to renovate Paris’s built heritage, with many monuments beginning refurbishment years ahead of the Games. For example, the Grand Palais, which hosted taekwondo and fencing, underwent a four-year renovation to enhance natural lighting, improve public access, and restore the building’s original central axis. The Place de la Concorde, which hosted BMX, skateboarding, breakdancing, and 3v3 basketball, saw its statues repainted and pedestrian access expanded and calmed.

Alongside the new infrastructure built in areas that needed it, the Games will leave a legacy of newly renovated monuments that now meet contemporary standards for accessibility, environmental efficiency, and support for non-motorised transportation.

Now that the Olympic Games are over, these wooden and metallic structures have been dismantled to be either recycled, resold, or reused in other projects. Much like grassroots community initiatives where locals pedestrianise streets and organise social and cultural activities, the temporary nature of these Olympic stadiums has reshaped our perception of how public spaces can be used and experienced.

A few years ago, Gensler adopted a similar time-sensitive philosophy when we put forward the audacious proposal to turn Notre Dame’s square into an ephemeral pavilion, cleverly pairing built heritage renovation with temporary public space activation. As the fire damage created a temporary vacuum at one of the city’s most historic gathering places, Gensler wanted to create a modest, yet emblematic, temporary and modular structure. With movable panels that can be opened seamlessly, this pavilion was planned to adapt its inner layout for larger services, exhibitions, performances, marketplaces, and other gatherings.

Looking Ahead to the 2028 Olympic Games

As the world’s attention now shifts westwards to Los Angeles and the upcoming 2028 Olympic Games, we ask ourselves: What can LA learn from this city-spanning experiment?

As opposed to previous Olympics associated with unnecessary large infrastructure that would become redundant after the competition, Paris 2024 has completely reimagined the temporality of its infrastructural investment. We hope to see Los Angeles carefully coordinating the necessary and large-scale retrofits of public transportation networks, sewage systems, built heritage renovations, and public spaces to be used for the Olympics, while making sure to pertinently respond to local needs during and after the competitions. Once the city uses what it already has, and builds only what it really needs, this is where tactical urbanism at scale comes in: anything beyond what the city really needs on a day-to-day basis should be built in the most inexpensive and short-term way.

It is this approach to temporality that really made the success of these Olympic Games and could make the success of futures ones: ensuring their perennial legacy by paradoxically using the most ephemeral architecture.

For media inquiries, email .