Libraries Are Crucial Social Infrastructure for the 20-Minute City

March 03, 2023 | By Elaine Asal, Christopher Rzomp, and Al-Jalil Gault

Today’s libraries are transforming — because they need to. Once known solely as places for books, libraries are pivoting and adapting to adopt new roles in society. Indeed, during the pandemic, they became the unsung heroes for many communities, providing valuable assets at the time of greatest need. By hosting vaccine and testing spaces, providing creative activities for stir-crazy families, and supporting food drives and clothing giveaways, libraries built something new atop their classic role as places for learning and a home for good old-fashioned books.

This evolution didn’t come out of nowhere, and even before the pandemic, libraries had begun shedding their old selves as simple book circulation centers. But the pandemic’s disruption created new energy for the evolution that libraries were needing to survive. Now that the floodgates are open, big changes are arriving quickly. Imagine a place where, in addition to all the physical books, our communities host students applying for jobs, seniors being tutored on digital benefits platforms, and an array of other programs such as concerts and clothing giveaways displayed in front windows. This is today’s library, an active community center that creates new possibilities for people’s lives through equitable access to empowering services, learning, and connection.

With these possibilities uncovered, what can we forecast for libraries in the future? How might the library play a new role in the vibrant cities that people want and need? And what does this mean for libraries’ physical locations and spaces?

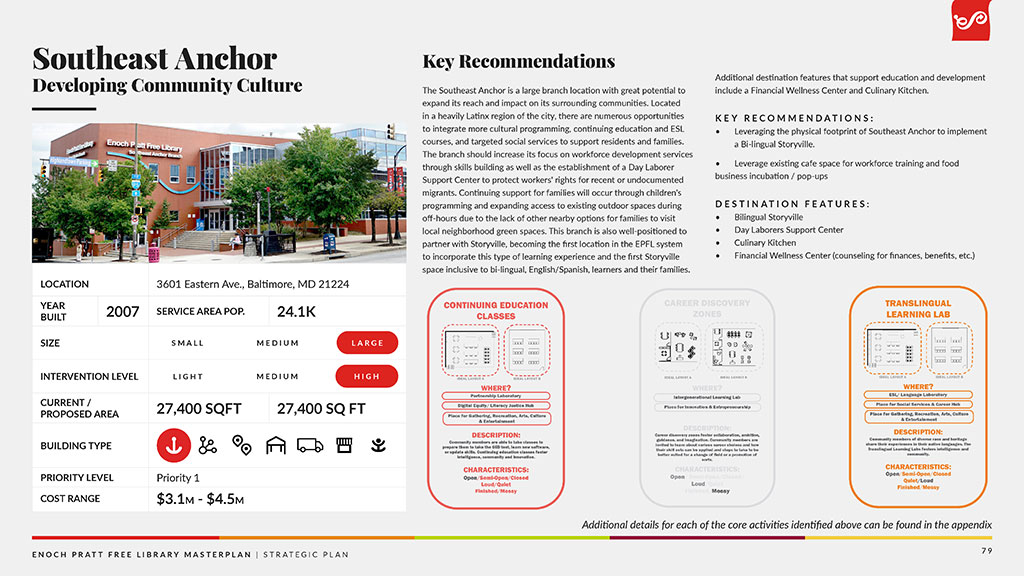

Our work for a library system in Baltimore highlights what some of those answers might be: moving away from books-only and embracing an evolutionary model with destinations for dynamic and experiential learning, building life skills and work skills, enabling citizenship (and its documented economic and social benefits) and community integration, and providing space and resources for families, nonprofits, and local artists.

Envisioning a future for the Enoch Pratt Free Library system

Gensler and our partners Margaret Sullivan Studio and the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance (BNIA) explored these questions in our master planning study of the Enoch Pratt Free Library system (EPFL) in the city of Baltimore.

EPFL had recently completed a strategic plan focused on equitable community placemaking through trauma-informed services and youth learning. Our task was to evaluate how well the existing branches were meeting the ideals of the plan and explore how the library might strategically grow while continuing to meet community needs in an equitable and comprehensive way. The plan recommendations needed to address facilities and service priorities for all 21 branches in the system for the next 10 years — all while remaining mindful of an already strained capital and maintenance budget.

Rich human stories, branch by branch

We used branch surveys, site visits, and staff workshops to understand behaviors of current library patrons and quickly saw that each branch has its own unique story and staff who work hard to support and connect to the families, teens, adults, and seniors who come in seeking help, resources, learning — and interaction with other people.

At the Canton branch, we saw something seriously memorable for a library setting: a parent-toddler Zumba class. In Hamilton, teenagers fill the space after school every day for a few hours to hang out in a safe and supportive space. At Forest Park and Cherry Hill, seniors and adults were making use of internet resources for job and health benefits applications. We also observed coat drives at the Brooklyn branch, clever window book displays at the Southeast anchor location, and outdoor concerts at branches in Govans. All of these formed a compendium of rich human stories centered around a library that had adapted itself to serve a specific community in meaningful ways.

Urgency, assets, and partnerships

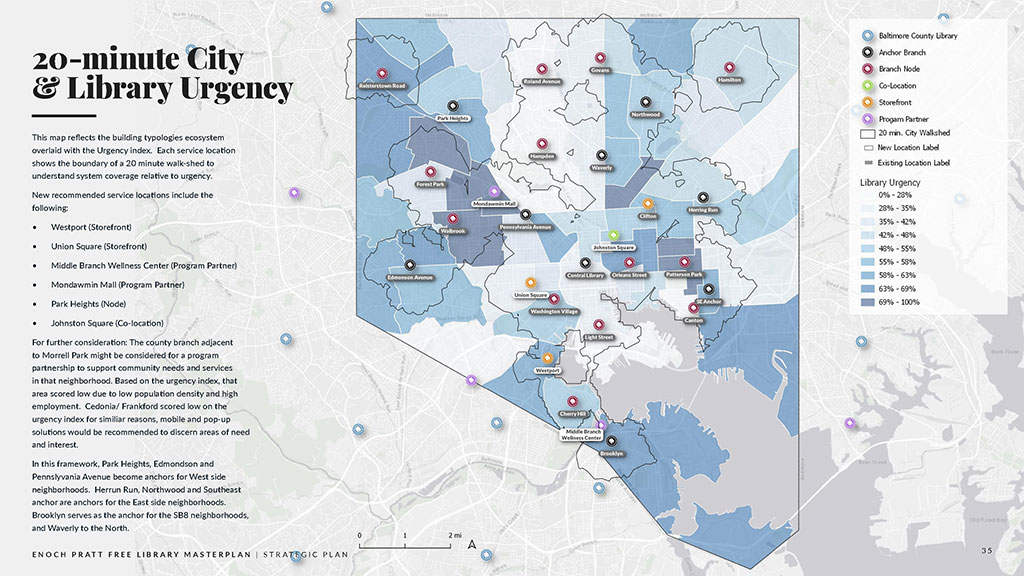

We developed two critical analyses to complement our user exploration: a Community Needs Assessment (also known as the Urgency Index) and a Community Asset Map. Both activities use the 20-minute city framework to evaluate a branch’s accessibility to its surrounding neighborhoods and the wider county and to understand opportunities for partnerships and shared resources in the respective locations.

Urgency Index: This assessment provides an index score compiling gaps in resources related to support that might be provided by a library. Factors in the urgency index include socioeconomic conditions such as internet access, unemployment, kindergarten readiness, population density, and availability of nearby recreation and job centers. We drew on data from the Baltimore library system’s longstanding collaboration with the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance to understand whom branches were serving, what programs were most successful, and where there might be opportunities to lean into strengths. From this we created a three-month activity snapshot, which highlighted gaps in branch location or services coverage.

Our team then overlaid existing library locations with proposed locations and a 15-minute walking radius to understand coverage across the city, showing the areas with the highest need. Based on this, we recommended priorities and targets to better allocate library resources through co-location or program partnerships.

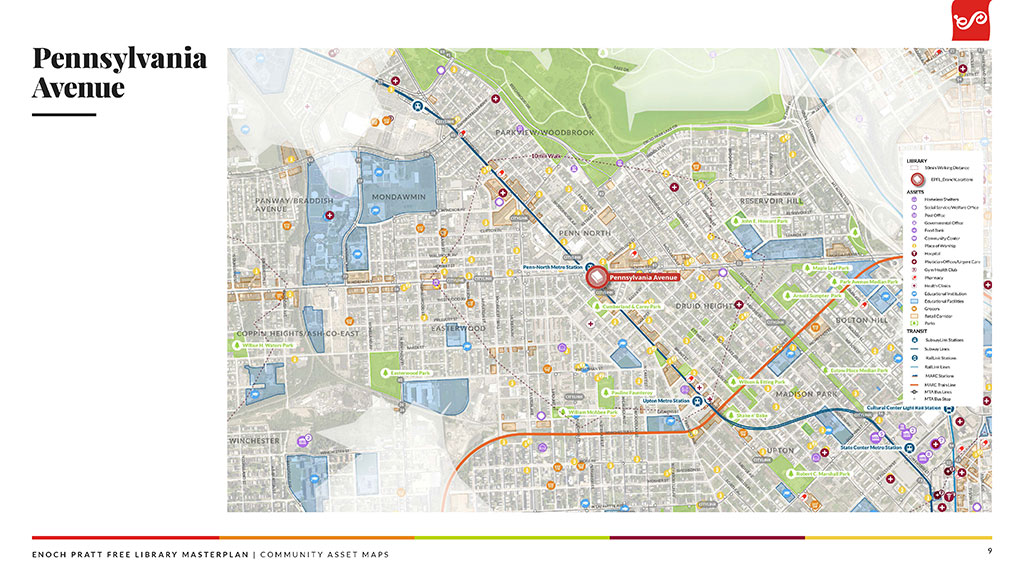

Community Asset Map: This analysis surfaced opportunities for the library system to align more closely with what’s happening in the local neighborhood by identifying geographic, social, commercial, non-profit, and public amenities and assets within a close radius to a library branch. Those existing amenities and assets then become good candidates for extending or amplifying programming that complements existing library activities.

With this understanding in mind, we started to document the potential program partners and user types that could increase the function and utilization of library spaces. For instance, one branch’s adjacency to several churches, a jobs center, and a high school suggested a wide range of opportunities for after-school programming, digital literacy classes, or flexible event space for meetings and gatherings.

Another branch was centered in a growing Hispanic community and medical campus, raising possibilities for bilingual early childhood education, food pantries, and a coworking space. Aligning the existing assets to unique amenities or attributes in the branch would reinforce an ecosystem approach for the overall library network, providing a baseline for neighborhood branches while offering unique destinations within certain communities. Each branch must respond to its community, and one size does not fit all. Our recommendations considered a range of facility types, from new and expanded anchors to partnership models co-located with schools or rec centers, and even pop-up solutions when a standalone brick and mortar facility wasn’t feasible.

The outcome: A vision for the library as critical social infrastructure

For Baltimore, Gensler’s study presents a scalable, data-informed ecosystem approach that enables adaptable growth for the future of the EPFL system. Based on the partnerships and work completed in Baltimore, our teams recently launched a strategic planning study with the San Francisco Library System, also in collaboration with Margaret Sullivan Studios, exploring a different set of challenges but centering equity in process and outcomes.

Across the United States and the world, library systems offer an incredible network of embedded, small scale, neighborhood-centered physical spaces with staff present to understand and serve their community. Our cities and communities need to recognize libraries for their full potential as critical social infrastructure at a time where cities dealing with income inequality, affordability challenges, and significant budget limitations rely more and more on the private sector to provide these resources.

There are five key takeaways from our experience with the EPFL:

1. Libraries remain one the most trusted civic and governmental institutions. They are beloved and offer a safe haven and engagement gateway for some of our most vulnerable citizens. The physical building, while its programming may change, is a symbol for stability and public investment in our neighborhoods.

2. Outdoor civic spaces are a major opportunity. Their importance and appreciation only grew during the pandemic, and some of our most impactful findings were about taking the library outside to engage outside of the traditional four walls.

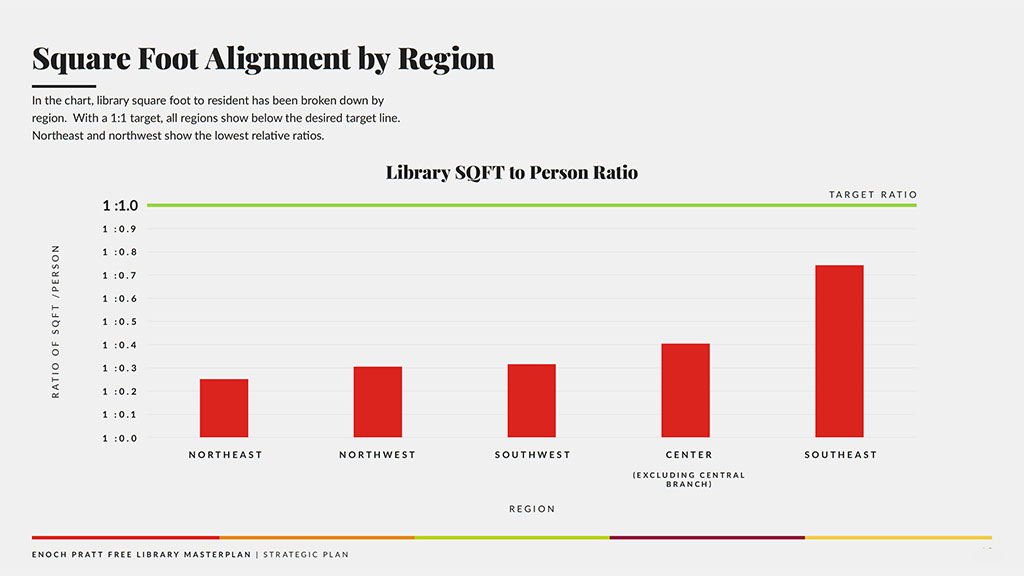

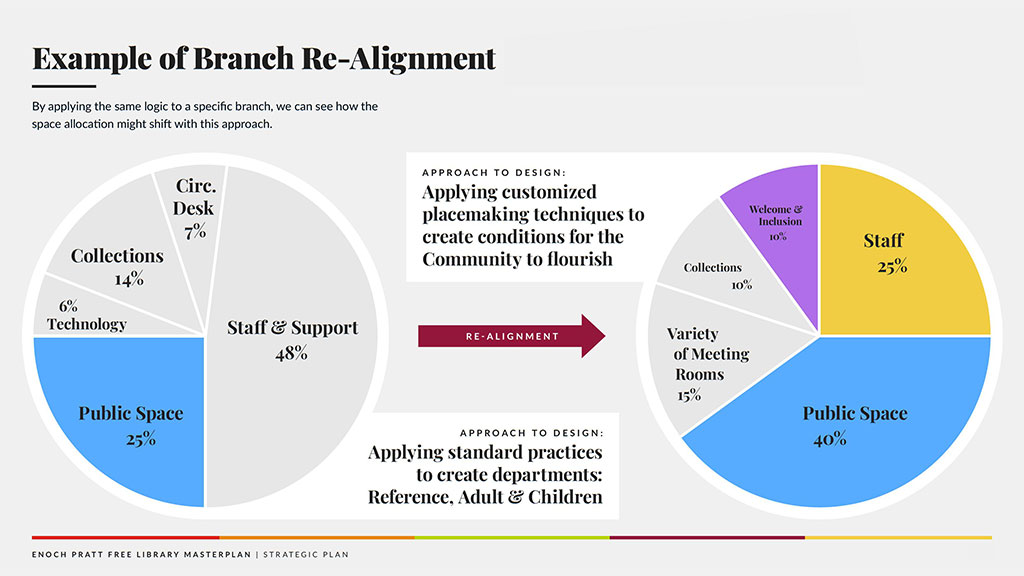

3. A realignment of services, programming, staff skills, and space usage must happen. This realignment is essential as decreases in physical book circulation continue in both well-resourced and underserved communities.

4. Realignment can’t happen in a vacuum: Maximizing community partnerships and adjacent assets is critical to enable greater physical utilization, community alignment, and diverse engagement.

5. Measuring level of service is more than just the amount of physical library space. In a world that interacts and learns anywhere/anytime, more agile forms of outreach like virtual programming, mobile libraries, and temporary pop-ups become essential to a comprehensive library service offering.

In its evolution from books to a kaleidoscope of new uses and spaces, the possibilities found in Enoch Pratt Free Library demonstrate to cities everywhere that the story of the public library is anything but finished. The need for these civic anchors is as pressing as ever, and by forging deeper connections with the neighborhoods they serve, libraries can take a more active role in creating positive social outcomes and more equitable cities.

For media inquiries, email .