Housing Affordability and Homelessness in Los Angeles: A Conversation With Roger Sherman

February 28, 2023

Housing affordability and homelessness are tragic and prevalent issues in Los Angeles, and there are several ideas around what constitutes solutions to these problems.

To learn more about these challenges, we sat down with Design Director Roger Sherman, who leads the Urban Impact Group at Gensler Los Angeles, for a conversation on housing affordability, homelessness, and innovative ways for reform in these domains.

What do we typically misunderstand about homelessness in Los Angeles?

Roger Sherman: The single greatest misunderstanding is that all or most unhoused people are what is termed “high acuity,” individuals incapable of ever holding down a job or being self-sufficient due to physical and/or mental disabilities. Less than 30% of the overall homeless population may be characterized as such, according to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA ). The implications of this misunderstanding are profound, to the extent that it affects the criteria for public funding, which almost exclusively is directed towards this high acuity subgroup. Because the high acuity population is the most expensive to house, requiring wraparound services and more rigorous requirements in the design of living units, oft-quoted estimates of $700,000 and higher per unit have become the norm, and in most cases, the units can take upwards of six years to complete.

We must ask ourselves: At a moment when three people are dying on the streets of Los Angeles each day, are public monies best spent exclusively on a select few of the worst cases, while the larger share of the homeless population who are significantly cheaper to house and more capable of returning to self-sufficiency goes unaddressed?

Due to the simple lack of affordable housing, it is this larger share of unhoused people, often referred to as the “hidden homeless” — which ranges from students who are forced to couch-surf or live in their cars to vulnerable seniors on fixed income — who are growing at an alarming rate. If the growing number of unhoused people is thought of as an iceberg, it is more impactful to reduce its volume by cutting away at its wider base (low acuity cases) than at its smaller tip (high acuity cases).

That is why Gensler’s Urban Impact Group is focused as much on solutions to the larger “hidden homeless” subgroup through the development of typologies of transitional and deeply affordable housing (see our Urban Awning project below), as we are on permanent supportive housing (PSH) for the high acuity group. This carries the additional advantage of working on projects sourced with less-regulated private funding, enabling them to be delivered cost effectively and expeditiously.

Could you talk about the Urban Awning project? How is this different from other affordable and supportive housing proposals?

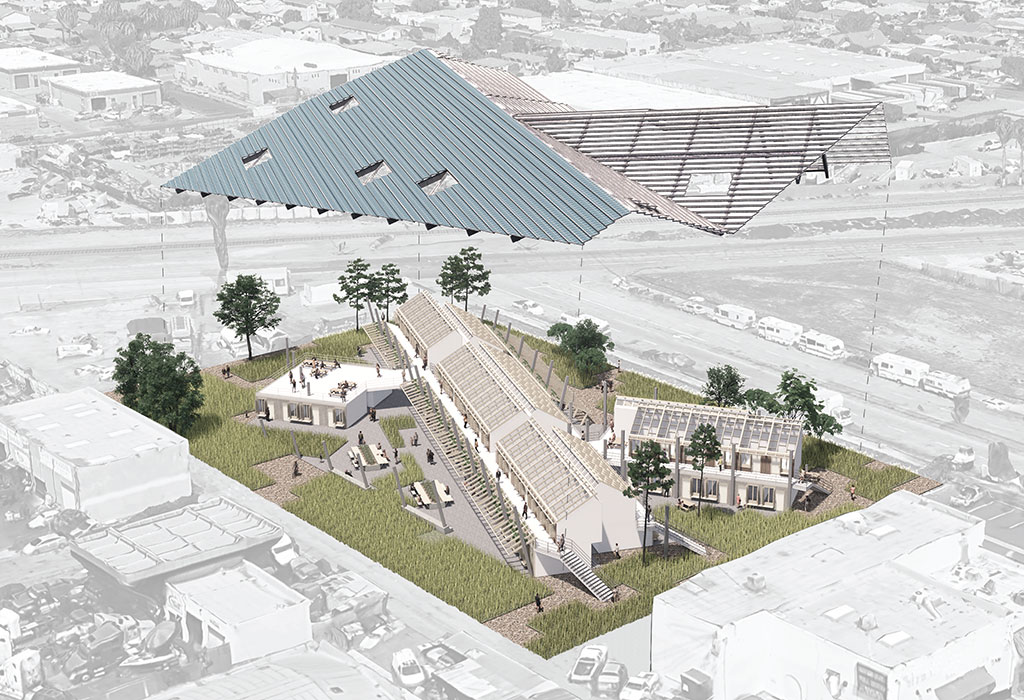

Urban Awning was conceived in response to the rising construction costs of supportive housing in LA. We asked ourselves: In rethinking how to build more affordably today, in what ways could we achieve more with less?” This question led us in turn to two more: first, at a time when homelessness and rents are both on a steep rise, what is the size necessary for a unit to be serviceable when subsequent options are to be on the street, in hot bedding, in a car, or on a couch? And second, in a climate as favorable/temperate as in Southern California, are there ways of rethinking how to reduce the amount of active environmental controls systems, energy, and water to only that which is absolutely necessary?

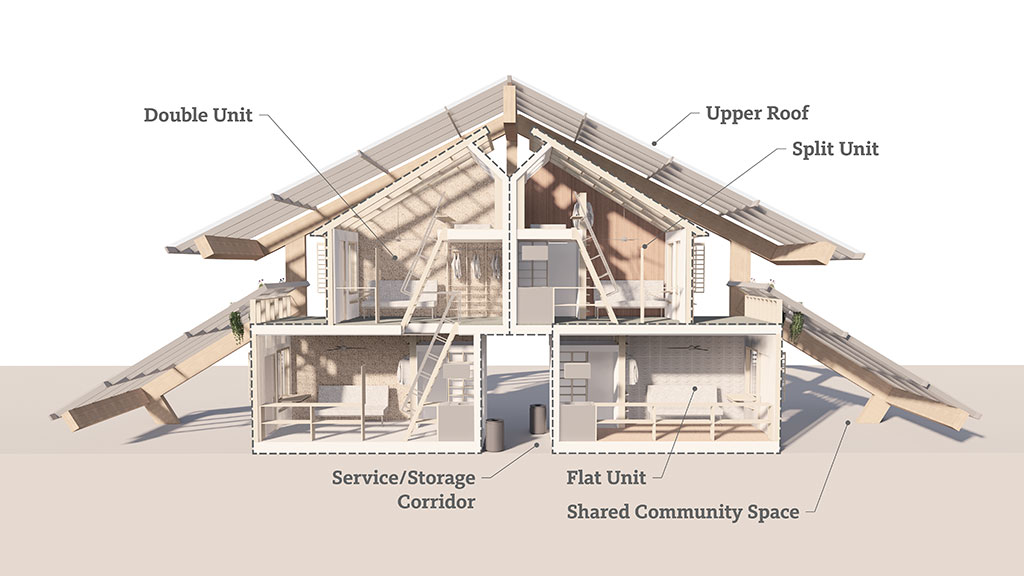

Both questions prompted us to fundamentally rethink the conventions of housing design. In response to the first question, we determined that units could be “right-sized” to include an ultracompact bathroom and kitchenette, with living and sleeping quarters collapsed into a single space made flexible by a foldaway sofa-sleeper. Additional living and dining spaces are provided in communal spaces just outside in a covered area.

In response to the question concerning climatology, we devised a great roof “awning” that creates a microclimate beneath, mitigating the effects of extreme weather while encouraging a sense of community amongst residents. The existence of the awning roof enables the units to avoid the need to be weatherproofed. Additionally, the awning mitigates the need for costly mechanical systems, save for a single baseboard heater and ceiling fan in each unit. Light and ventilation enter through a polycarbonate roof and strategically placed wall openings fit with shutters to modulate privacy and breezes. Finally, in two-thirds of the units, a mezzanine is provided, which can be alternatively used for storage or, on colder nights, a sleeping loft.

It is worth noting that on account of its space efficiency, Urban Awning possesses the same density in terms of occupants as a building twice its size and mass. This is not only more sustainable in terms of the reduction of materials used (and embodied carbon), but also results in a cost of up to 50% lower than a comparable project of conventional design. And finally, the reduced profile of a project that essentially looks like an enlarged version of a ranch house makes it a less imposing neighbor (NIMBY-friendly).

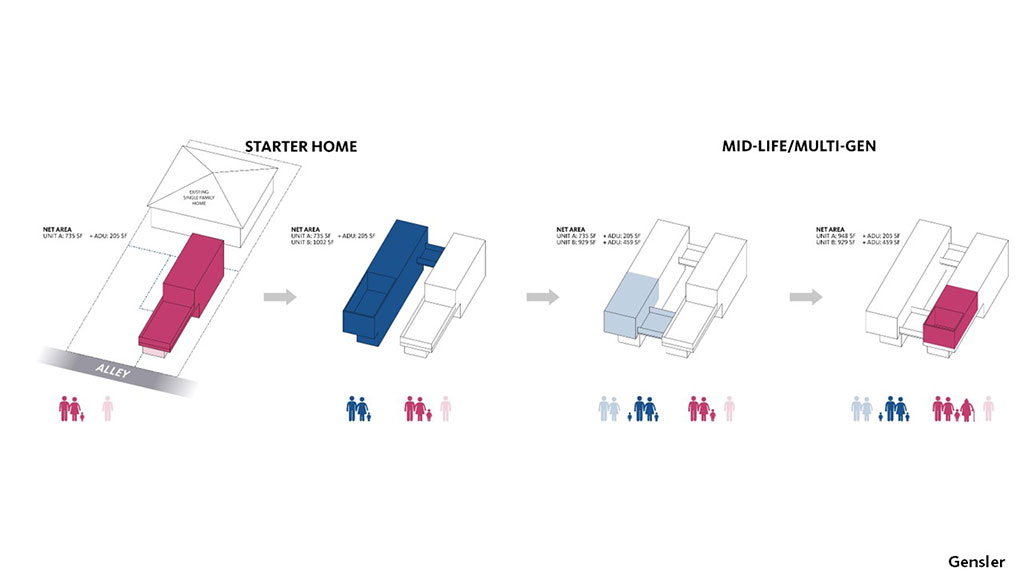

Are there affordable pathways that lead to owning property? What opportunities exist for developers to capitalize upon the abundance of smaller lots? And how should we think about co-living solutions or multigenerational living in the context of affordability?

In part 2 of our blog series, Roger will investigate these questions.

For media inquiries, email .