Equity and the 20-Minute Neighborhood

As we continue to engage in a national conversation about the persistent inequities in our underserved communities, it’s essential that we leverage the power of research and engage residents as we redesign our cities and neighborhoods. Gensler’s City Pulse Survey revealed that two thirds of urban residents believe we should completely rethink city life in a post-pandemic world. Nearly 80% of Black urbanites, who have recently weathered some of the most devastating impacts, agree. The pandemic, social protests, Black Lives Matter, and the ongoing murders of Black men in the U.S. have placed a spotlight on the inequities present in Black and Brown Communities.

These communities face vulnerabilities such as concern for safety, persistent disinvestment, and access to affordable housing, healthcare, and economic opportunity. Research shows that safety is paramount to a community’s sense of well-being and Black residents feel less safe than any other racial group. The ongoing threat of police violence towards Black men from George Floyd to Tyre Nichols contributes to the distress. Black and Brown people living in cities are the least satisfied with their current living situation, and over half are living paycheck to paycheck. Communities across the country are in crisis — the time to reimagine our collective future is now. We must use research, community co-creation, and the principles of the 20-minute neighborhood as we rethink the design of our cities, towns, and neighborhoods to build a more equitable future for all.

The Power of Equity Research

Since Gensler’s Center for Research on Equity and the Built Environment was established in 2020, it has funded over 40 research proposals focused on the topic of “Black Lives and Design.” The Center was created to foster a deeper understanding of the critical issues facing Black communities and has explored how design can be a catalyst for meaningful change. Researchers have investigated design justice, amplifying Black voices, equitable solutions and development, unconscious bias, creativity and the Black experience, climate injustice, economics and policy, as well as housing and displacement.

Our designers leverage the Center for Research on Equity and the Built Environment, as well as other research partnerships to unpack complex social justice issues and develop new insights that expose barriers to progress and discover new solutions. Similarly, in my two decades of teaching architecture and urban design studios, I’ve seen how data and analysis can identify and quantify the most pressing challenges facing our communities. It provides an approach to design that builds a deeper understanding for the implications of our projects on the communities where they are situated. It can also inspire a new generation of designers to view design as an essential tool for improving our cities and strengthening our communities with equity at the foundation.

Community Co-Creation

Designing for people is only possible when you design with people. Community-based design charrettes, listening sessions, and surveys are vehicles to engage communities and to gain a deeper understanding of how injustice and inequity manifests within the “lived experience” of individuals. It is important to collaborate with members of the community to reimagine the future of our cities, towns, and neighborhoods.

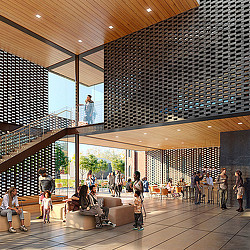

Our design for the Newark Community Museum of Social Justice is an example of how understanding history and place, while also amplifying voices, can improve design outcomes and maximize positive community impact. The concept for the project was informed by a design process that included input from city officials, cultural institutions, architecture students, and residents to create a museum that highlights Newark’s history of activism against racial injustice and focuses on community aspirations for the future. The project transforms the 1st Police Precinct, the flashpoint of the 1967 Newark Rebellion, into a space that celebrates Newark’s rich history of activism and provides a multigenerational space for learning, storytelling, and healing. The co-creation process was essential for informing the program and creating a vision that will have a meaningful impact on the community’s future.

Equity and the 20-Minute Neighborhood

20-minute neighborhoods can be a transformational concept for rethinking our communities, but only if they prioritize access for everyone. This means focus on developing a strong neighborhood retail base, reimagining neighborhoods as employment centers, viewing access to the internet as an essential public utility, providing a diversity of affordable and mixed income housing, increasing access to healthcare and wellness, expanding mobility options, enhancing the public realm, and sharing community assets.

Recent architectural studios I’ve taught have challenged students to reimagine the American city through the lens of equity and the 20-minute neighborhood model. Using Newark, New Jersey as a case study, students explored how the principles of a 20-minute neighborhood can revitalize the city’s downtown and neighborhoods to become a catalyst for positive change. One studio focused on Newark’s Downtown District and the other on the Lincoln Park neighborhood, each with its unique challenges. Students conducted research, data analysis, field investigations, community engagement, and a series of urban mapping studies intended to reveal the complex layering of the underlying structures and systems that influence physical form as well as the social, economic, and cultural functioning of the city. Their investigation revealed a deeply embedded and lingering presence of inequality and injustice that has tempered present day realities.

Two new Gensler projects in these neighborhoods — each informed by equity research and community co-creation — we hope can be catalysts for positive change. Gateway, an existing 1.6 million square foot mixed use development in downtown was originally conceived as an inward-facing complex separated from the life of the city, has recently transformed into a welcoming space that embraces the street and reconnects the community. 1033 Broad Street in the Lincoln Park neighborhood preserves the character of the neighborhood by restoring the façade of the South Park Presbyterian Church, the only remaining element the church destroyed by a fire in 1992. It provides much needed affordable housing, space for community organizations, as well as a performance venue that celebrates the neighborhood’s rich musical history.

This is the moment to design for fundamental change. As designers, research should guide our understanding of the unique history and systemic barriers to progress that exist in the places we build. We should engage the community and raise their voices to enhance the authenticity and impact of our work. And, finally, we should embrace principles of equity and the 20-minute neighborhood and conceive projects that are not designed in isolation but as part of a larger whole.

Equity research and community co-creation applied to the principles of the 20-minute neighborhood offer a model for addressing many of the issues facing underserved communities while providing new tools for designers to reimagine our cities, towns, and neighborhoods and to build stronger, more resilient, and equitable communities.

For media inquiries, email .