Designing for the Future of Theater and Immersive Entertainment

Our Media and Entertainment leaders discuss what’s next for immersive theater and performing arts venues.

To appeal to new audiences and ensure lasting relevance and long-term economic health, performing arts and cultural organizations are looking for new ways to engage, entertain, and attract audiences.

We sat down with Ryan Ihly, a studio director in Gensler Los Angeles’ media, technology, and sciences studio, and Ann Morrow Johnson, global leader for Gensler’s Entertainment practice, to unpack the power of immersive entertainment and experiences to reinvigorate performing arts venues.

Audience participation is the touchstone of immersive theater. As this type of entertainment becomes more popular, how do we design flexible performance spaces that blur the boundaries between performer and audience?

Ann Morrow Johnson (AMJ): Much of immersive theater has a vast range of small-scale intimate moments that touch only a few people in several square feet of space through to large, collective gathering moments. This is a hallmark of Punchdrunk productions like Sleep No More and their more recent Viola’s Room, where audience members follow a character or path through the set to gain plot insights and intimate moments. This creates an incredibly memorable and provocative fan experience that engages people in community as they exchange information and anecdotes about their unique takeaways about the production, but also encourages return visits, as there are potentially infinite ways to experience the show and discover the space.

In order to create these moments, the ability to have hyper-localized controls across a range of spaces is crucial. Recent advancements in point-source audio are a great example of this type of individualization — wherein production can direct sound at a single person in an open room to show control that can follow spatial and time queues. Tools like these allow for maximum flexibility and can create a feeling of intimacy across a range of immersive-style shows.

Ryan Ihly (RI): I think there are three distinct ways of looking at this — two traditional and the other reemerging. On the traditional side, we have what is known as a “black box,” essentially an adaptable canvas without fixed seating, or distinction between audience and stage areas. While a black box has technical flexibility and rawness, it lacks ambiance, character, and architectural flexibility to accommodate multiple configurations.

The evolution of flexible “studio theaters,” with enhanced performance and AV equipment, as well as multiform aspects that allow for changes in room configuration such as form, size, and aspect ratio, accommodates new and traditional performance modes without losing the intimacy and architectural character of spaces. The other emerging typology is the use of found space or non-normative theater space that encourage a blending of performer and audience and breakdown of singular perspective of audience and stage.

What used to be known as environmental theater is emergent in non-linear narratives where audiences co-create their experience. A recent dance performance called “Mirror Neurons” literally placed a mirror reflecting the audience back to itself, negating the stage. Dancers, strategically placed in the audience, and music and audio tracks compelled audience participation in a way that unfolds throughout the show.

What role can the arts and theaters play in activating and transforming underutilized real estate? How can this be designed with long-term success and feasibility in mind?

AMJ: Some of the coolest shows, with the most texture and depth, lean into the history and often the awkwardness of their converted surroundings. It creates a sense of authenticity unique to site-specific performances that you get to peek into oft-unseen historic buildings and the unique nooks of those spaces. Whether packaging a series of rotating shows so that there’s always something new to see, or a way to evolve over time, a constant toolset within a space allows for a multiplicity of experiences that can enliven spaces for new generations and audiences to discover.

RI: An important aspect to consider is the position of the artist and creator in finding ways to push the use of space, both traditional and found, in creating new typologies. What we think of as traditional spaces have emerged over time, from new forms of drama to music. A contemporary recital hall has its roots in a domestic Renaissance music room and a courtyard theater traces back to outdoor courtyards of Elizabethan England.

Today, we are working with developers and artists to bring emerging art forms to real estate properties as new models of cultural experiences. This is happening in bespoke spaces, but also in underutilized storefronts and public spaces.

Technology has a role here as well, with emergent interactive technologies allowing for individual responsiveness within a space. Our Digital Experience Design practice is at the forefront of this and is helping underutilized spaces increase engagement and foot traffic.

Tech-forward integrated performance venues that pair live performance and all-encompassing visuals (a la The Sphere or COSM) have burst on the scene as a popular and rapidly growing entertainment/performing arts category. How are we adapting to satisfy new tastes and interest in augmented performance?

AMJ: Just as film began to move from physical sets to green screens to LED backdrops, so too are we seeing adaptations in theatricality. This means that there are massive new capabilities to give audience members the perception of being transported to other worlds. But just like film, what is appropriate for each story or experience is a case-by-case basis. Sometimes you want the most out-of-this-world experience, like that of the custom-built avatar performing arena for ABBA Voyage, while others, like Third Rail’s Ikaros, performed with just a few lights, speakers, and props in a public park call for simplicity and physicality.

RI: In some ways we are seeing the evolution of the “showroom” — more Las Vegas-inspired and part of larger engagement in mixed-use experiences. I think it also falls back on artists to push the bounds of new technology and performance methods and develop specific responses to new opportunities rather than laying older media onto new. With emergent performances and visuals, architecture can complement and adapt to new artist and user needs.

Whether high ticket prices, exclusionary crowds, or the relatability of the content itself, theater, opera, and dance performances can have high barriers to entry. How can performing arts venues reestablish themselves as cultural hubs for everyone?

AMJ: Perception of exclusivity is both the problem and an opportunity for many performing arts venues. The more forms of invitation we can create for more different types of audiences, the more likely they are to resonate. Institutions that view everything from their programming and marketing to their physical spaces and ticketing structure as opportunities to invite in new audiences are beginning to see an increase in not just participation but a shared sense of identity with their communities.

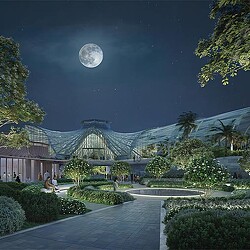

Stages in Houston is a great example of this. Gensler worked with the client convert a warehouse that formerly housed the Museum of Fine Arts into a community-driven theater space that wanted to redesign the experience of going to the theater-going experience from “curb to curtain.” Investing in this converted warehouse allowed Stages to have new spaces for rehearsals, workshops, become a premiere training ground for young artists, and introduce the neighborhood to theater in a new way.

RI: Accessibility and inclusion have become key elements in the design of performing arts venues. Increasing engagement and audiences is important for our culture, as well as the health of venues. Very few cities can have standalone venues for all the arts, so many complexes are designed to take on multiple forms of performance. We’ve spent a lot of time looking at how to address these markets and user groups, as well as developing venues that respond contextually to what makes a city unique.

Theaters can be looked at as financial engines that can help redevelop areas of a city. Lincoln Center and many others began as catalysts for redevelopment, but today’s venues must also be open, transparent, and reflect the community. They can’t be imposing or on a plinth. These are institutions that help define a city and its culture; they should by that measure be for everyone.

How are you seeing trends and learnings from other industries translate to the future of performing arts design?

AMJ: Performing arts venues are exploring how to create opportunities with new and existing spaces. In theaters, this often means celebrating performance art in new ways, whether that be primarily digital, experimenting with co-creation, or using a portion of a campus never contemplated for public/performance use.

RI: Theaters traditionally were places of meeting and entertainment, where audiences were rowdy at times. It has gotten a bit too formal. We have started to look to sports and other popular entertainment formats to reimagine the theater experience, asking questions such as where does the experience begin, is it on an app, parking and arrival, what does the experience at the show feel like, how is the food and beverage, and how long do you want to linger afterwards or beforehand?

Every sector seems to be focused on hospitality and the comfort of spaces, and lessons to increase engagement and draw people back based on the quality of their experience. For a performance venue, this encompasses every aspect of customer and artist experience in both the front-of-house and back-of-house. Personalization, seamlessness of transactions, wait times for and quality of concessions, and tiers of services are all hospitality and sports elements being incorporated into performing arts venue design.

For media inquiries, email .