What Sports Venues Must Do to Be Tomorrow’s Cultural and Economic Anchors

August 03, 2022 | By Andrew Jacobs

Sports and entertainment architecture is a significant generator of community culture. An anchor of community calendars, these iconic venues are right up there with museums, cathedrals, government buildings, and other locations of significance. This is the architecture of passion, community, performance, technology, optimism, and experience. In some cities and towns, the stadium is equivalent to the cathedrals of previous eras, dominating the skyline and proclaiming a community’s desire to be considered true believers. In other cities, an arena draws people as if on pilgrimage from far and wide to see the only appearance of a traveling performer. Smaller village venues serve as community gathering places that host weekly athletic or entertainment events, so neighbors can gather and share an experience. In all cases, the venue is about bringing people together to celebrate, to mourn, to participate, to believe, to embrace, to jeer, to laugh, to cry — in ways they cannot do alone.

As communities evolve, so must their architecture. The pandemic, coupled with immersive digital communication, dispersed many community borders, changing how people form bonds and how people work, play, and receive entertainment. People now can find others who are “just like me” without leaving the sofa, work remotely from their office, compete in e-sports anywhere, and stream new releases at home. However, these achievements have caused strain on physical community building. There are more reasons to stay home than there are to go out, especially if our architecture remains stuck in outdated modes.

Sports and entertainment communities, for the most part, have endured despite these changes and sports architecture remains a point of unification for many. One couldn’t name another building type that brings as many people together at such a scale despite socioeconomic differences. Accordingly, sports and entertainment architecture is the design of cultural and economic anchors that (still!) draw people together. It is the architecture of all people.

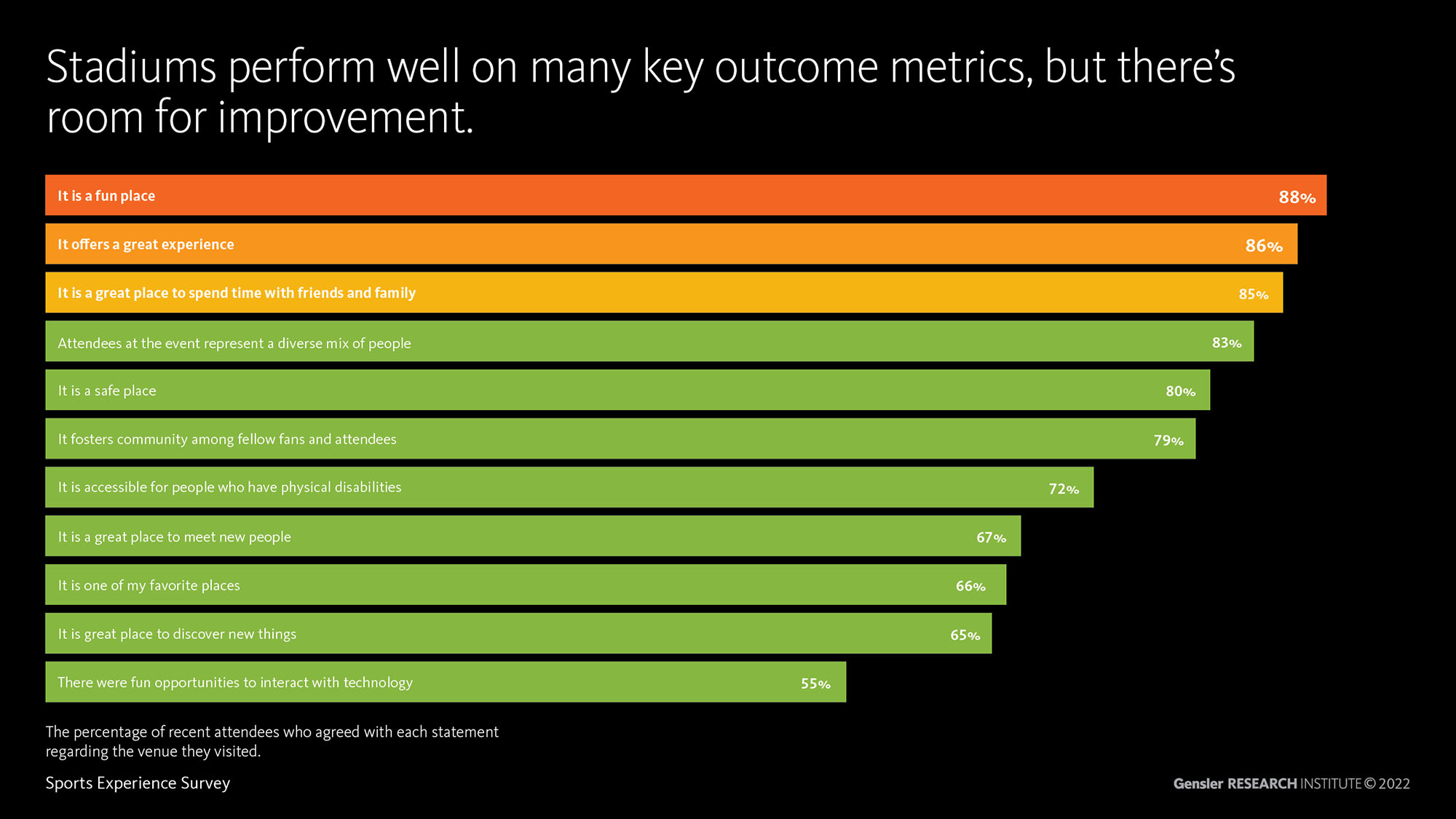

Over the past two years, the Gensler Sports practice has teamed up with the Gensler Research Institute in a series of research-driven initiatives focused on quantifying the sports and entertainment experience for venues. Most recently, we have begun a series of surveys of recent sporting event attendees. (View our Sports Experience Survey results here.) Our data is helping us develop solutions that are tailored to meaningful guest engagement, including better social experiences, amenity locations, and entry experiences, among other points of focus. It is helping us create architecture that is fun and engaging, and, most importantly, a community anchor.

Sports and entertainment buildings are typically designed with an inward focus around the event taking place within. This has led to many venues with a nice front door but minimal activation at the street level. As the number of culturally significant events has grown over time, so has the number of people drawn to the venue. As our research shows, this is especially true among younger generations who want to feel a part of something larger than themselves. More people are coming to venues, even if they don’t have a ticket (some, just to say they were there!). In response, venue-focused districts have begun to develop around venues to feed off their draw.

Gensler has designed several districts around existing venues that push activation up to the front door. Examples include recent developments around existing venues, such as Fifth + Broadway outside of Bridgestone Arena in Nashville, and the Milwaukee Bucks Entertainment District, also known as the ‘Deer District,’ at Fiserv Arena. Both developments benefit immensely from the crowds generated by the venue. In fact, during the Milwaukee Bucks’ NBA championship run more people gathered outside of the arena at the Deer District than inside the venue. As a cultural and economic anchor, the arena generated larger crowds than it could handle inside, but the exterior and surrounding amenities were fit for the task. Similar opportunities exist in myriad sports venues, and building owners are starting to respond.

The Gensler-designed Hub on Causeway, a mixed-use development at Boston’s TD Garden Arena, is a prime example of how urban sports and entertainment venues will be designed in the future. Taking a previously blank, inactivated façade and building a rich tapestry of entertainment, retail, hotel, office, and residential attached to the arena, Gensler created a seamless connection to the city. Like the Bucks’ use of the Deer District, Hub on Causeway saw an influx of crowds during the Boston Celtics’ playoff run.

A current study we have developed is based on a similar idea. Rather than building a grand staircase and an oversized entry, we created a small village that hides the fact that you’re climbing two stories to get to the main concourse. It’s appropriately scaled for everyday use, so that even on non-event days, it feels like a place where you want to be. Overlapping porches and balconies will be active year-round and especially so when the big event is happening. The venue is a part of the district and not apart from the district.

We will soon see sports and entertainment venues designed to be seamlessly integrated into districts. For both renovations and new venues, outward-facing activation will be key. The district and the venue will share infrastructure, but the experience will be human scaled — a truly meaningful development for one of architecture’s most important genres, and all the cities it helps activate.

For media inquiries, email .