How Civic Architecture Can Strengthen Our Social Fabric

Recently, the U.S. Surgeon General warned in an advisory about the mental and physical health challenges Americans face concerning loneliness and isolation. These public statement advisories are typically reserved for alarming public health challenges that require immediate attention, such as the opioid crisis or cancer. In this case, the advisory stated that “Loneliness is more than just a bad feeling — it harms both individual and societal health.”

At the same time that our society is facing a loneliness epidemic, politics in the U.S. is polarizing faster than other well-known democracies. Polarization is not the same as disagreement and respect for alternate opinions and engaging in constructive discourse is at an all-time low. According to a study conducted by researchers at Brown University, since the 1970s, political polarization in the U.S. has increased more dramatically than in eight other countries, including the U.K., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Germany, Switzerland, Norway, and Sweden. This polarization doesn’t just lead to gridlock in government but “contributes to negative effects within our families, workplaces, schools, neighborhoods, and religious organizations, stressing the fabric of our society.”

An Antidote to Isolation: Our Civic Buildings and Public Spaces

The way we design our built environment can help. The design of our civic buildings and public spaces is one of the key determinants of our personal and societal health because our surroundings influence our behaviors and our civic fitness. Public spaces are extensions of communities and offer places where residents can interact with each other and their government and gain a sense of belonging. The CDC even includes built environment recommendations in its “Promising Approaches to Promote Social Connectedness.” Through the creation and expansion of public green spaces, designing places to support community gatherings, and creating design features that encourage community participation we can promote “more frequent, high-quality relationships” between people.

Historically, our town halls and civic centers have provided us with public space to gather, connect, socialize, and dialogue with each other. The town hall, along with the market and the church, served as the communal hubs of a city. The civic plaza was a place for discourse where ideas were debated, and respect garnered. And in a time before the automobile, the proximity of these spaces to each other and the pace of the pedestrian allowed for encounters with friends, acquaintances and strangers creating familiarity, sociability, and trust — the bonds of communal society.

The town hall began as a two-story structure typically facing a plaza. In its simplest iterations, public meeting hall space was located on the upper floor and the ground level of the structure was focused on open air market activity — considered vital to the merchant class and prosperous for the town. This combination, or ‘mixed-use’ also provided a diverse, critical mass of people throughout the day to create an interesting and desirable place to socialize.

Through the centuries, as towns grew and city management became intricate and specialized, the buildings housed more records and required more clerks, and the architecture became grander and more imposing to project increasing city power and pride. Access became limited. Also, the bustling market activity taking place at the ground level moved further away from the town hall — creating a segregation between the civic sphere and commercial realm that many times deadened the activity in the area.

The Eastvale Civic Center

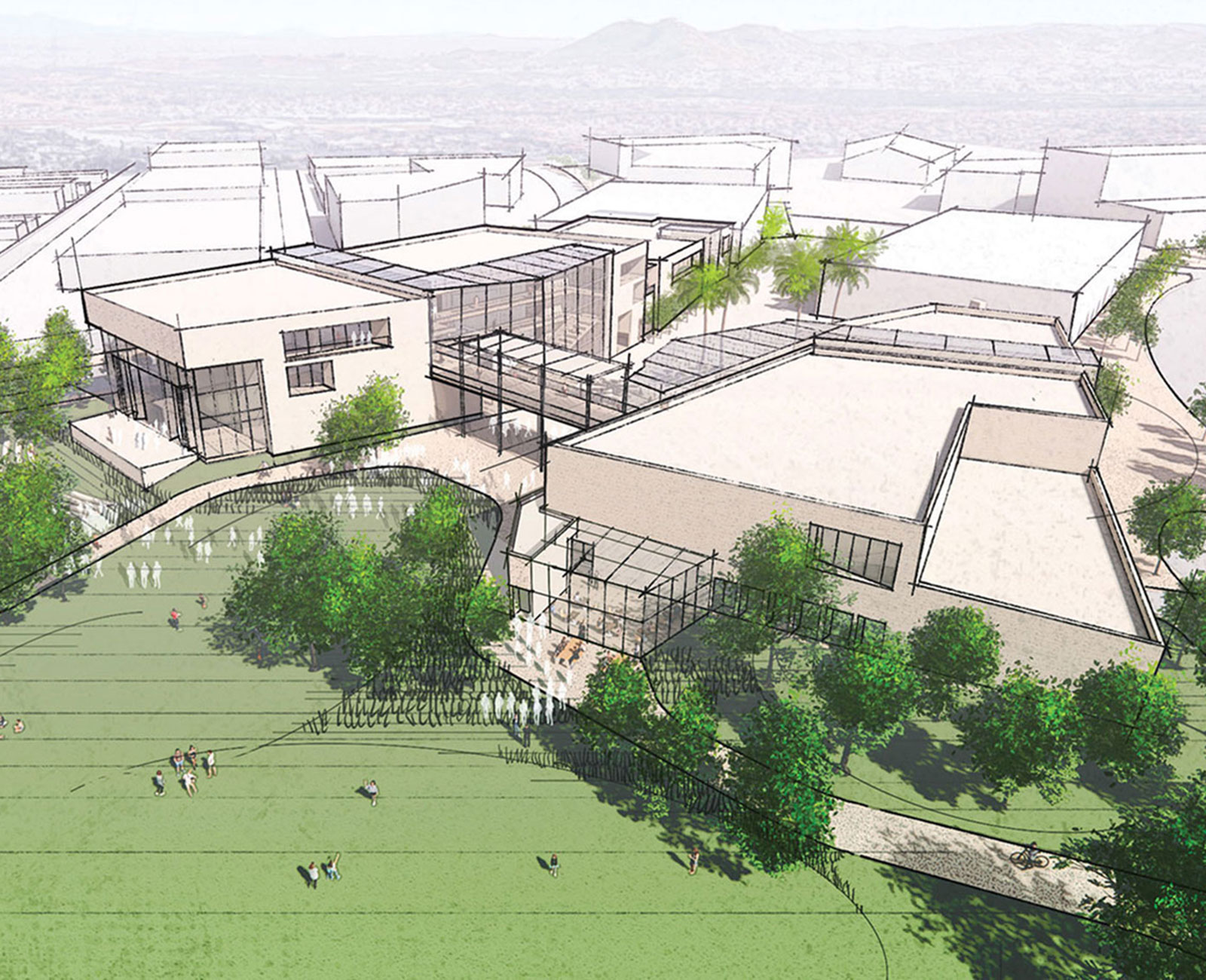

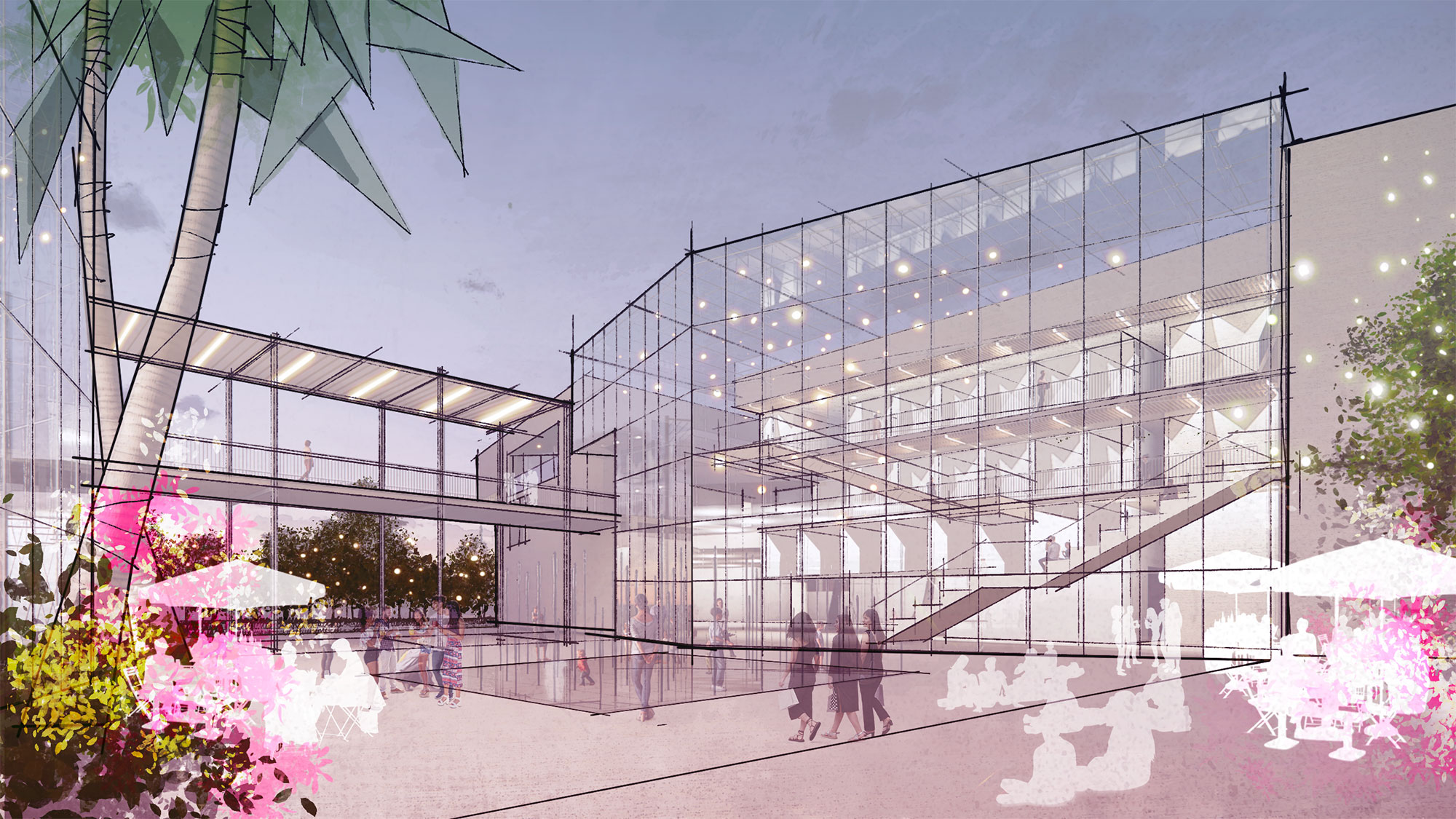

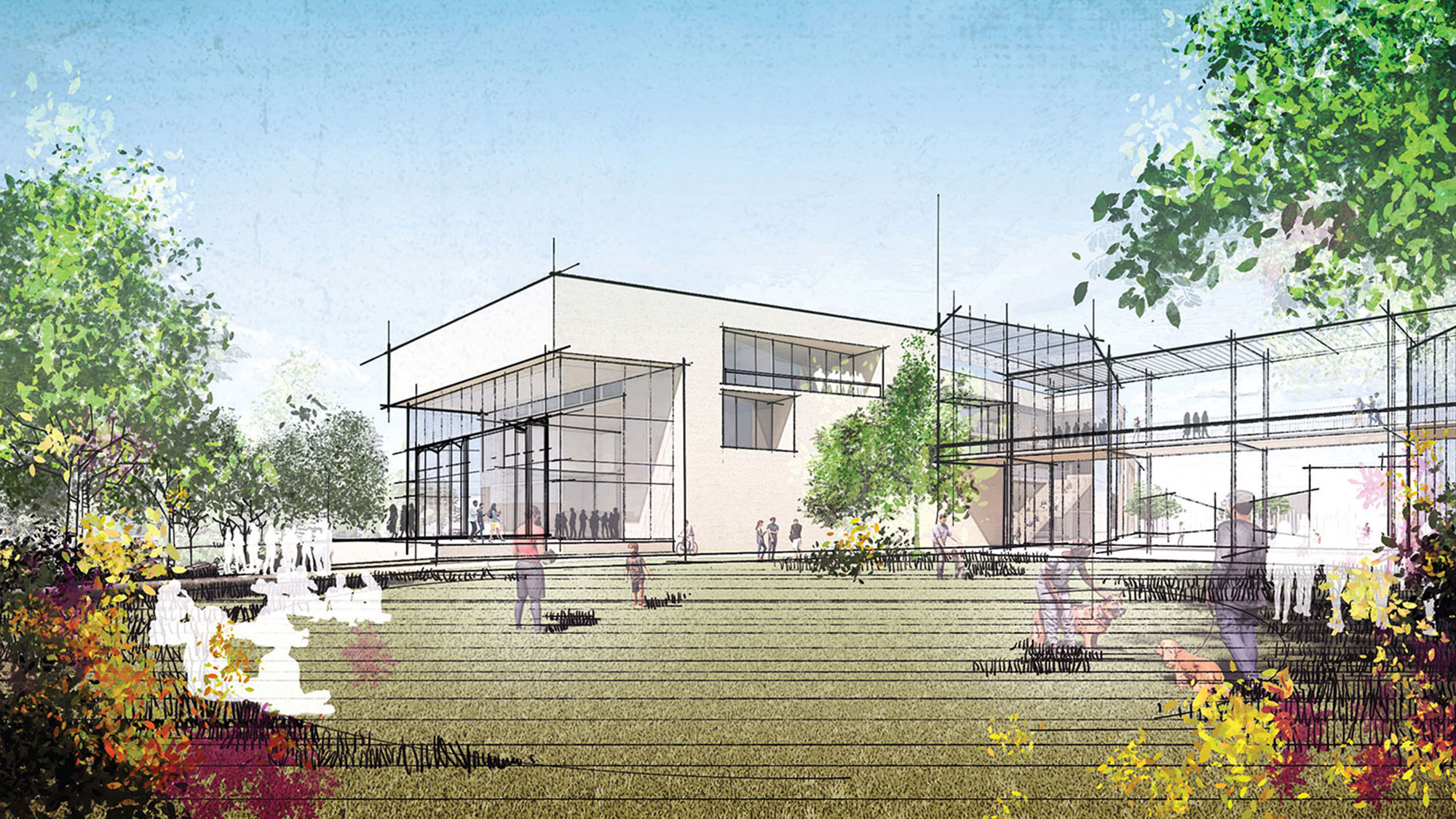

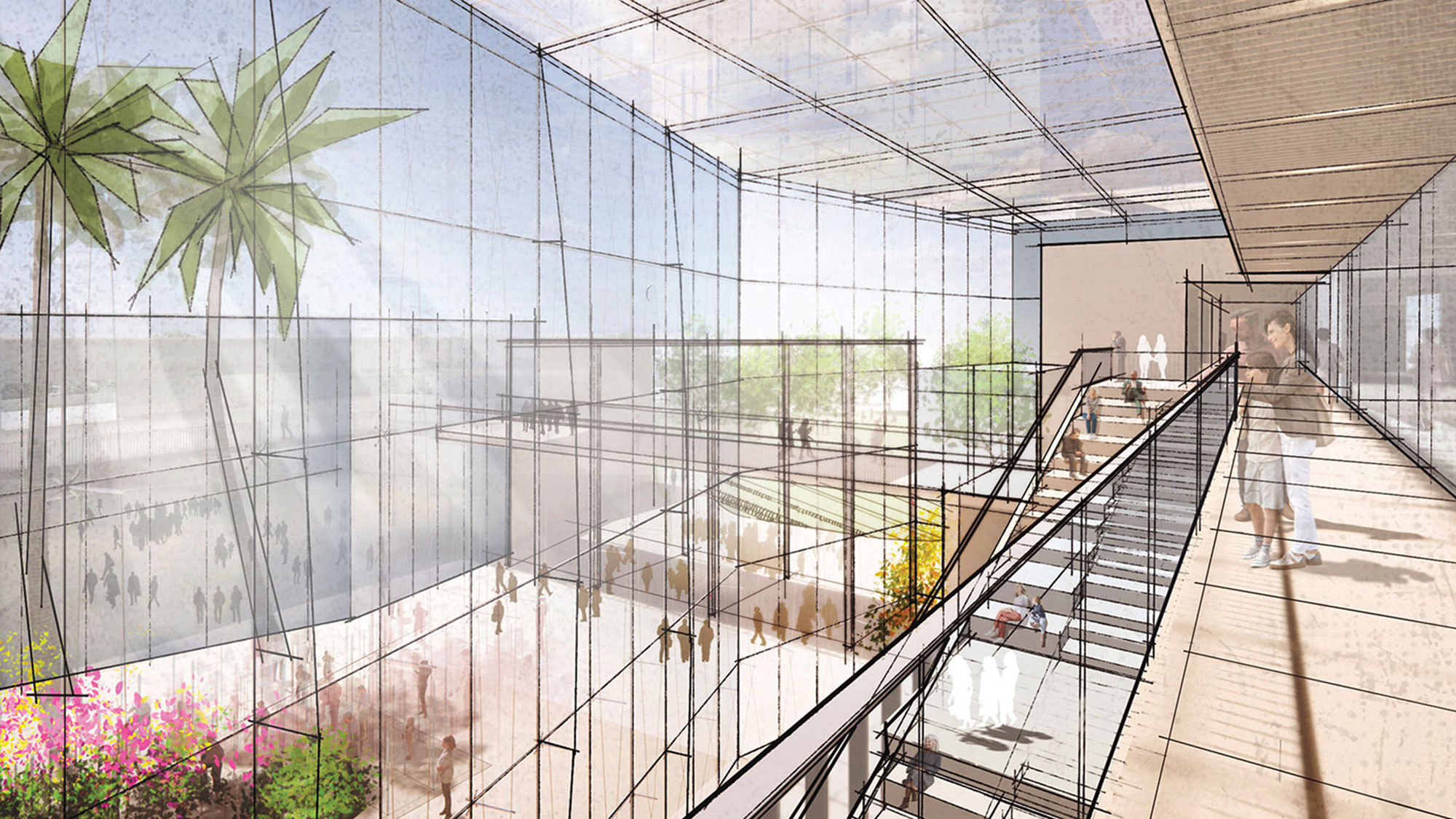

For the new Eastvale Civic Center in Eastvale, California, we have partnered with the city to create their first bespoke civic presence as a transformation from these recent trends. The new city hall, library, and police station are designed to be as open and transparent as the local government they will represent. There are visual and physical connections between the indoors and outdoors, as well as a reintegration of the market and commerce that enlivened the earliest town halls. The new civic center is less intimidating and more inclusive to its citizens, with a feeling of the government working alongside the constituency, while the buildings represent strength, permanence, prestige, and pride.

Civic PlazaThe central civic plaza provides an inclusive space for farmers markets, concerts, and more, and acts as the key gateway into the public atriums of the city hall and library buildings and the public entry to the police station. In addition, various ground level cafes, exhibit spaces, and multi-use community rooms can be accessed from the plaza, creating an enlivened public amenity space.

A park anchors one end of the master plan providing a green oasis in the city. It provides open, unprogrammed, and flexible outdoor space for a diversity of uses. The park also includes an amphitheater for small concerts, plays, or outdoor movie nights. The city council chamber is a multipurpose space that opens up to the amphitheater via oversized glass folding doors to allow for diverse types of major events to occur between the two spaces.

The master plan includes 495,000 square feet of mixed-use development providing entertainment, shopping, hotel, and office space. Two parking garages serve most of the site’s parking needs and have been programmed with extensive ground floor food and beverage opportunities to activate the ground level. The new dining grove is reminiscent of the site’s history as a former orchard, and becomes an enticing, shady amenity for eating and relaxing with friends. Co-locating these commercial uses with the public amenity spaces and civic buildings guarantees the participation of a rich and diverse cross section of the community.

A Communal Living Room

The new Eastvale Civic Center will become more than a place to pay a parking ticket or renew a passport. The design will allow for the collaborative and transparent workings of local government alongside its citizens, where elected officials, city employees, and police officers can intersect and connect with the public on a daily basis to instill trust and deepen community bonds. It will form a key third place between workplace and home for residents and visitors to socialize, recreate, shop, learn, eat and drink, experience culture, and connect with each other in what will become the community’s true communal living room.

The irony of the world’s population reaching 8 billion, combined with the great migration from rural areas to our densifying cities, all while we are becoming more socially isolated, should not be dismissed. The culprits are many — from the internet and social media to a global pandemic to increasingly polarized politics. But through the physical design of our communities and our core civic spaces, we have an opportunity to reimagine our cities, restore some connections between the civic and commercial realm, and provide places for people to connect, unite, and grow as a community.

For media inquiries, email .