Cities and the Public Health: Our New Challenge in Urban Planning

April 08, 2020 | By Andre Brumfield and Carlos Cubillos

Editor’s Note: This post is part of our ongoing exploration of how design is responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dense cities remain our best bet for providing opportunities and connections — if they’re designed to support residents’ wellness.

In our overlapping moments of hibernation, virtual work, and meditation during the COVID-19 pandemic, we realize our vulnerability and appreciate community and togetherness. Ironically, this is happening at a time when we cannot get close to each other. Gensler’s Cities + Urban Design teams from the Americas, Asia, and Europe are actively exploring new ideas on how planning can respond to the unpredictable new conditions that urban life may bring. Here we share the topics on our virtual whiteboard—our emerging notes for future thinking.

The Importance of Good Governance

Policy, governance, and enforcement play a fundamental role in our cities’ present and future. We believe that urban planning, more than ever, can suggest directions, facilitate conditions to help restore balance between the natural and the engineered, and build healthy lives and resilient environments.

Historically, the health of urban inhabitants has been intrinsically bound to the practice of urban planning. Unfortunately, public policies and professional practice have weakened that bond. In the wake of all that has happened recently, we see an opportunity to shore up that link as a means of building healthy lives and resilient environments. This will require us to play a larger role with our city agencies to stress the importance of physical planning that should be closely tied to public policy to adapt to our new reality.

Yet this would not be the first time that an epidemic has triggered changes in our field. Cholera outbreaks like the one in London in the early 19th century influenced improvements in sanitation. Tuberculosis eruptions in New York in the early 20th century led to improvements in housing regulations and public transit. SARS flareups in Asia at the onset of the 21st century spurred upgrades in medical infrastructure and systems to monitor and map the disease.

It’s clear that this pandemic is different, and it will force city officials — as well as their planning authorities, local, regional, and national governments, and practitioners — to think differently about how we shape the urban environment.

Dense cities still offer our best options for housing, education, employment, social interaction, and cultural and leisure activity. They also remain a viable way to accommodate expanding populations on finite territory.

Rather than spelling the death of cities, the COVID-19 pandemic will serve as a moment to fine-tune them. Cities can become life-regenerative ecosystems that are better able to support what is most important: the relationship between people, their health, and natural systems. We now have a new opportunity and an obligation to rethink how we plan and design our urban environments—to narrow the gap between people and place, and make both more resilient and flexible to adjust to unforeseen forces that impact how cities operate as an organism.

A Different Approach to Open Space

Seeing the way that people have flooded parks, greenways, and bike paths in recent weeks, overcrowding them and at times forcing authorities to shut them down, one wonders whether the current size, amount, proximity, and interconnectedness of open space is addressing our needs for today, let alone tomorrow. COVID-19 has caused us to develop a more nuanced appreciation of open space’s social and therapeutic potential, such as access to better air quality and more physical activity, among other benefits.

Safety and security now takes on an entirely different meaning, one that goes well beyond Oscar Newman’s Defensible Space theory. Urban planning must now push forward the idea that safety in the public realm is an investment in public health, thereby requiring us to think differently about open space in the face of this crisis. Cities and their local governments must embrace and manage security in our public realms to address this crisis and future pandemics.

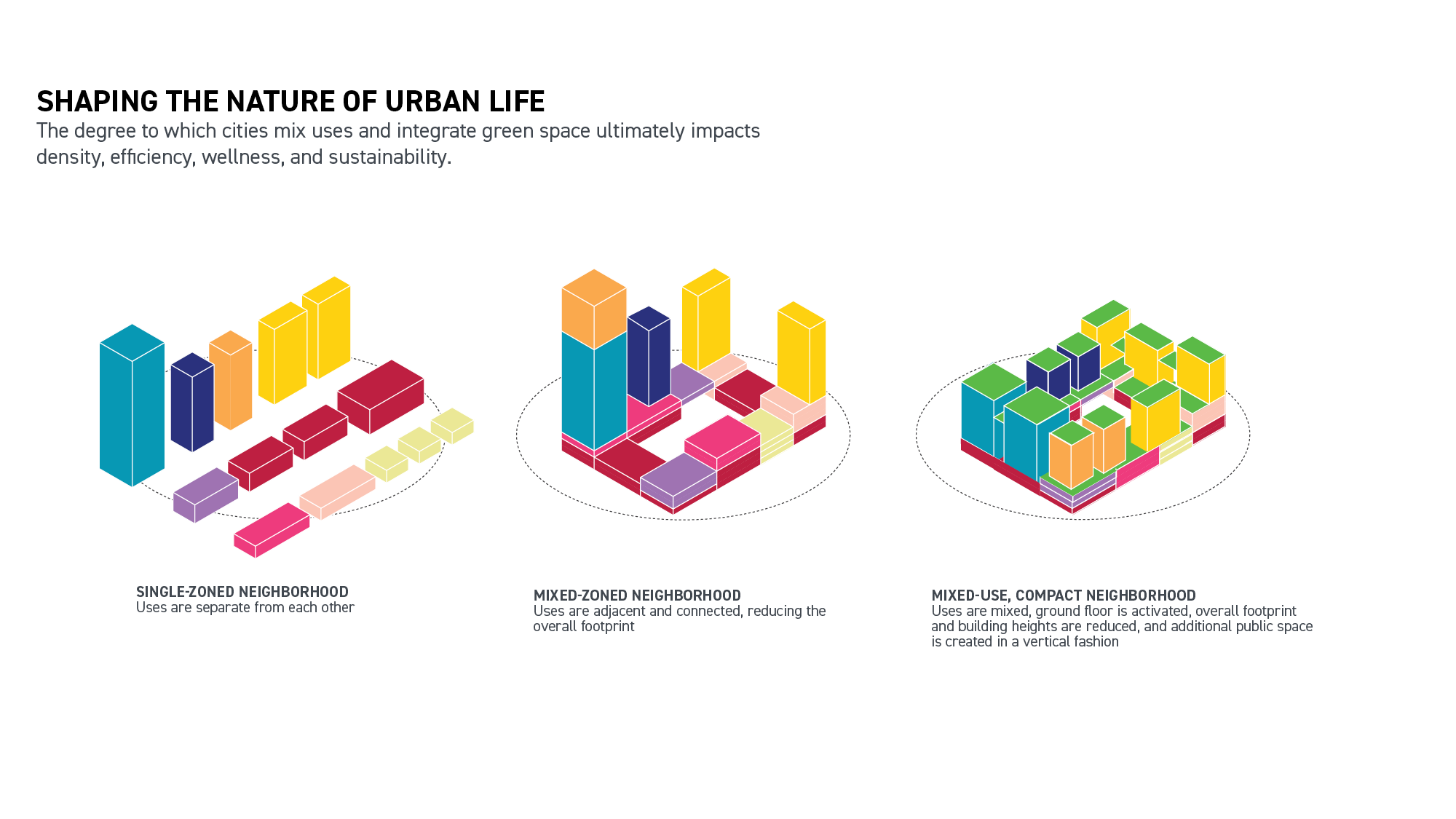

To find some potential direction on these issues, it’s worth looking at what a few dense cities across the globe are doing. In Singapore, for example, buildings in dense environments are increasing the amount of green space by re-organizing themselves vertically and providing sky gardens and connected green roofs for people to move through and socialize, for children to play, and for urban farms to produce food. In Barcelona, where superblocks and common courtyards seem to be a civilized counterpart to dense, unhealthy environments, the continuous presence of complementary uses at the ground level offers a way to create supply-chain options that allow neighborhoods to support retail and services for residents. The result is a mix of uses that creates efficiencies, promotes wellness and sustainability, and spurs greater density.

Density and Its Relevance in The Context of Public Health and Resilience

In this urban millennium, cities are serving as the most fundamental expression of density, and they will continue to attract people because of their ability to enable community, connection, and convenience.

Of course, the idea of density is under intense scrutiny in this era of physical distancing, despite the many positive outcomes associated with density in the urban environment. This is why the central question for city planners is: How can cities make themselves stronger by reconsidering the nature of density and its vital relationship to public health, wellness, and resilience?

Cities and their high densities are not exclusive victims of COVID-19. Low density and small towns in Italy and Spain have been equally affected, while dense Asian cities appear to have implemented successful controls on the impact of the virus. Barcelona, with a density of 16,000 people per square kilometer (41,000 people per square mile) is denser than New York City, with 10,200 people per square kilometer (26,400 people per square mile). The entire population of NYC would fit in half of its current size if it had the density of Paris, which is 21,000 people per square kilometer (54,400 people per square mile).

It’s worth noting that density should not be conflated with congestion, which resulted in the squalid, overcrowded environments found in New York City’s tenements in the early 20th century and Chicago’s overcrowded Black Belt in the 1950s. These congested conditions were systematic creations. The former was the result of prejudice against the arrival of immigrants and the lack of public infrastructure to support a rapidly growing population. The latter was a reaction to the Great Black Migration and indicative of racism bleeding into public policy and other institutions. Both led to substandard housing conditions and other urban ills that scarred the urban form of many cities for decades—with many still recovering.

These regrettable instances did not force cities to abandon density, but it did teach their leaders and urban planners to adapt to better and more appropriate approaches to density. As policy makers, designers, and citizens, we learned from these mistakes and worked to create a better environment.

The Benefits of The Polycentric Model

Density offers efficiency, opportunities for wellness, and community connection in unparalleled ways, when applied thoughtfully. One of the most inventive ways we now see density realized is through the polycentric model, in which self-sufficient districts are distributed across cities and function like urban villages. Such models have the potential to improve the quality of life, promote walking, and free up space for other uses, such as parks and gardens.

In Paris, officials are looking to implement such measures in the form of the 15-minute city. Under that model, the majority of residents’ needs—from work to shopping to leisure activities—would all be found within a 15-minute walk or bike ride from their homes. These urban villages could ultimately prove successful in the French capital because it has the density needed to pull it off. Other cities such as Portland, Detroit, Dallas, and Chicago are all exploring versions of the 15-minute, or in some instances 20-minute, city.

Likewise, Barcelona is already implementing the aforementioned superblocks, or collections of nine blocks arranged in a neat three-by-three-fashion. Car traffic is able to freely circulate around the perimeter of each superblock, but most vehicles are barred from the interior. As a result, Barcelona is taking space that was devoted to a single use—car travel—and transforming it into space open to multiple uses—walking, biking, playing, lounging, eating and drinking, and so on. In that sense, the superblocks become as much about health, community building, and sustainability as they are about alternative modes of mobility.

Thanks to strategic urban planning, both Paris and Barcelona serve as examples of how dense cities can better embody community, wellness, and resilience through redundancy, mix of uses and generations, and decentralization to help residents both satisfy basic needs and live fuller, healthier lives.

Exploring New Ideas to Preserve the Strengths of Our Cities

Planning always wrestles with the future, and the future appears increasingly uncertain in the COVID-19 age. We must now look for flexible and adaptable responses to our issues of urbanization. The lines between office, home, and leisure activities are blurring, requiring open spaces, buildings, and residences to fulfill multiple purposes in a defined amount of space.

Thus, how can we design cities and buildings to evolve over time to become more fit for place and purpose? What if our parking lots, garages, and public buildings could be equipped with adequate connections to electricity, water, and sewage, which could quickly allow them to effectively respond to a temporary use? What if we could rely on a system of streets with enough redundancy to allow predetermined closures to vehicular traffic and be used as spaces for people at specific times of day and evening and during emergencies?

These are the questions we must now confront to optimize our cities in the face of the current – and any future – health crisis. Going forward, our challenge will be to expand our thinking while holding true to the principles that we feel make cities and their neighborhoods strong, vibrant, and self-sufficient.

For media inquiries, email .