The Third Lane: Rethinking Street Design for the 21st Century

By Dylan Jones

In cities across the country, the adoption of dockless electric scooters as a legitimate mobility solution in 2018 was, by all accounts, unprecedented. Bird quietly launched a batch of scooters on the streets of Santa Monica in late 2017, and a year later they were being used in more than 100 cities. Competitors quickly jumped in as dockless mobility took off and $3 billion in venture capital flooded the market.

Wherever the scooters appeared, there was a mixture of excitement and serious concern. Their success reflected a desperate need in cities for a local, cost effective, and easy mobility solution; but in many markets, they’re all over sidewalks, stuffed in trash cans, or tossed in lakes. The joy these riders experience while zipping about their day is matched by the anger of pedestrians and motorists, who experience them as a new obstruction. Drivers and pedestrians both feel threatened.

This year promises a second wave of growth. As the snows melt on the Eastern Seaboard and across the upper Midwest — expect to see hundreds more communities flooded with scooters. This is more than a fad. The business case for operators remains bullish, demand is everywhere and capital is abundant. So, what does the explosive growth of this particular mobility solution tell us about the changing dynamics of city life? And how can we better shape the city of tomorrow to respond?

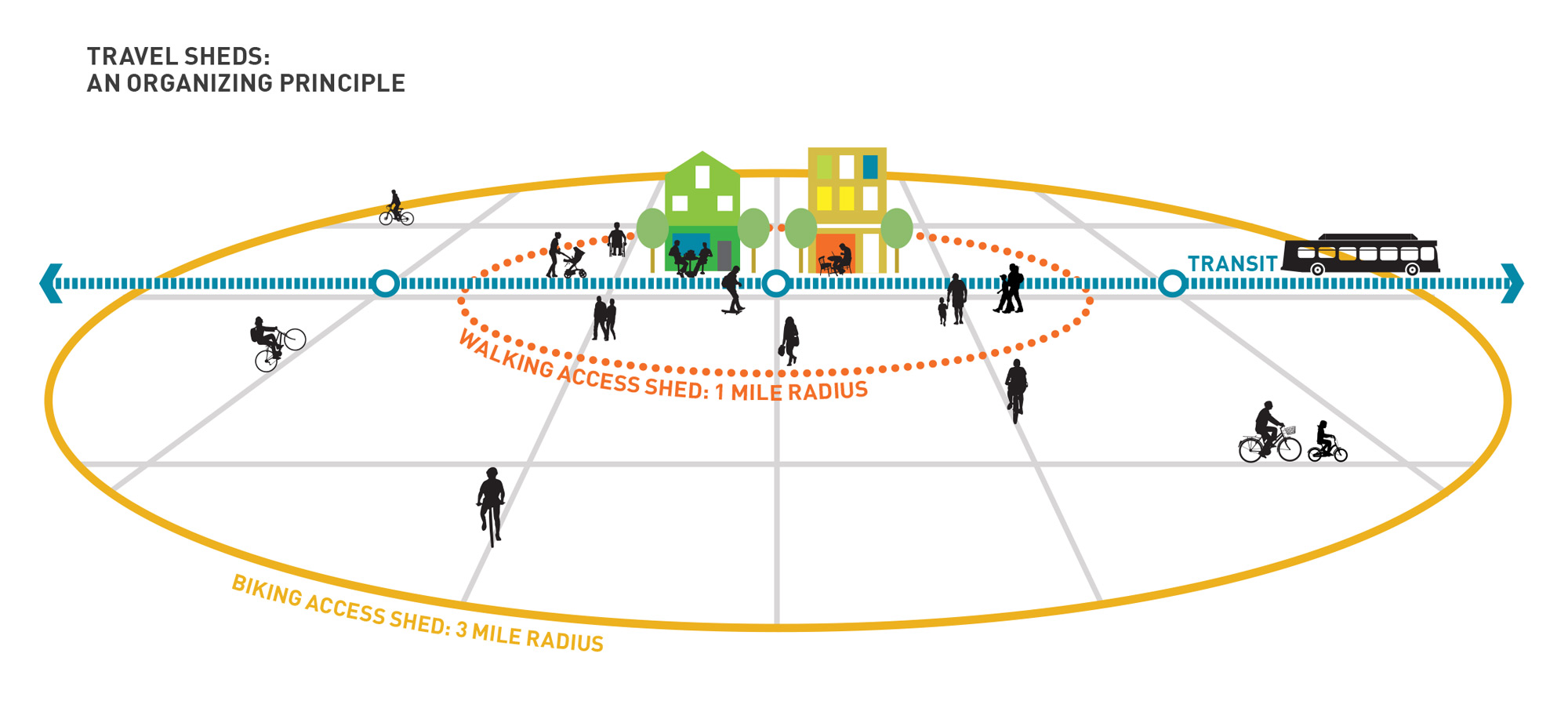

Transit planners think a lot about the “access shed,” especially when considering the links between transportation and land use. In planning terms, an access shed is the distance an individual will travel to connect with another person, good, or service. So, the access shed around a transit station is defined by how far someone is willing to walk (or bike or drive) to and from the station. Each mode has its own access shed, based on time and speed. People will generally travel up to 15 minutes, which equates to approximately a half mile for pedestrians, almost three miles for bicyclists, and eight to ten or more for drivers.

Given that the vast majority of people walk to stations (and policy goals aim to reduce greenhouse gasses), planners have always focused on the pedestrian half-mile radius around stations, sometimes referred to as a transit-oriented development or transit-oriented community zone. As a first-last mile solution, scooters are a tantalizing addition that can greatly expand access sheds around fixed-route transit — thus greatly leveraging public investments.

The scooters themselves travel up to 20 mph (but are often limited by regulation to less), easy to operate (especially by a generation that were weaned on kick-scooters and wheeled shoes), and cost-effective enough to manufacture and deploy in great numbers. Even when a user isn’t connecting to transit, electric scooters increase an individual’s range of access. Cross-town meetings too far to walk are suddenly within easy reach and daily errands can be a breeze. Anyone interested in saving money on parking (or car ownership entirely) has a legitimate option for making the vast majority of their daily trips.

As many are struggling with the high costs of housing, options like these are more than just a fun alternative — they are a necessity. And it shows: adoption rates are off the charts. According to initial research, they are viewed positively (70%) and have higher adoption rates amongst women and lower-income groups. All this despite the fact that there is no path officially designated to the devices.

From our model of mobility, we understand that every mode includes a vehicle, a path, and an experience. As a vehicle, the dockless electric scooter is a mashup of a surprisingly old mode (the toy kick-scooter) and contemporary technology in the form of compact rechargeable batteries, a GPS device, and an app for digital payment and location tracking.

Our contemporary streets were designed to support only two modes: pedestrians on the sidewalks and cars on the roadways. Streets are kept clear of obstacles to maximize flow and speeds for cars that have only gotten bigger, faster, and more numerous. Sidewalks, on the other hand, accommodate amenities such as street trees and furnishings, utility equipment, road signs, bus stops, newspaper boxes, parking meters, public payphones and countless other incursions.

Bicycles, after tremendous efforts by advocacy groups, have only recently been given a dedicated right-of-way in too few locations. The design solution has too often been a line of paint for protection along a zone shared by gutters and loading zones.

Scooter riders are currently faced with a choice: take the roadway (with cars – danger!), use the sidewalks (with pedestrians and utility poles – danger!), or share bike lanes (assuming they exist). The vast majority of issues being raised along with this incredible micro-mobility phenomena are related specifically to this fact.

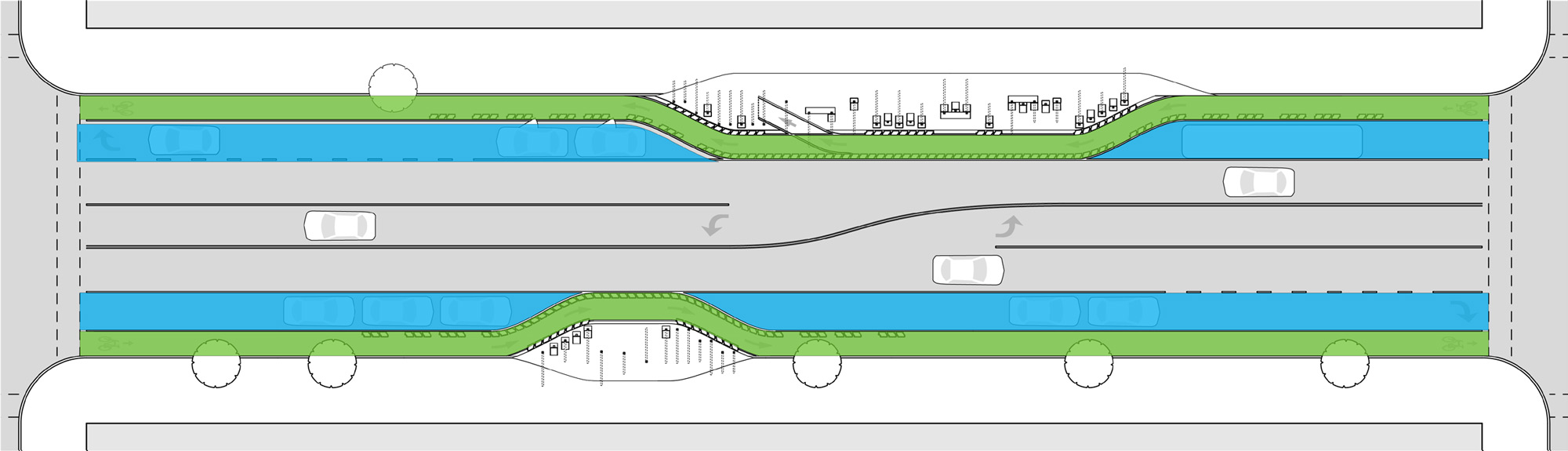

What we need in our cities is a Third Lane. A safe, efficient, intuitive, universally accessible, and fun Third Lane. At Gensler we’re looking hard at this, recognizing electric share scooters are just the leading edge of a massive shift in mobility patterns. The same tech advancements that helped fuel the meteoric rise of shared scooters are simultaneously improving bikeshare networks, which have adopted dockless systems and invested in pedal-assisted e-bikes.

When a flock of small electric vehicles can service a huge portion of local trips in compact communities, the inefficiencies of using privately owned, one-ton automobiles for all trips — no matter how short or long — become all too apparent. Change will help support cleaner, safer modes that respond to the needs of a much broader cross section of our populations. The scooters littering sidewalks today reflect a basic need and desire. Design can help solve the challenges and safety concerns moving forward.