From Indifference to Serendipity: Experiments in the Art of Living Together

April 29, 2021 | By Roger Sherman

In physics, when two populations of particles are mixed, one of two reactions can occur: those constituent elements can either merely rearrange themselves to accommodate one another, or they can actually form bonds with each other. The process of urbanization — more specifically densification, or the experience of living in closer quarters together — is not dissimilar. In this context, the design of housing can be seen as nothing less than the orchestration of the conditions under which those connections — in this case, social rather than chemical — are formed.

In the decades following World War II, returning veterans and their families were encouraged — and in fact incentivized — to invest in the presumptive American Dream of a single-family home of their own. The rapid suburbanization that ensued resulted in a pattern of land use that came to dominate cities like Los Angeles, which as it grew horizontally bore unintended consequences such as sprawl, disparities among localities, and other inequalities, which are only today being reckoned with.

Largely, these are problems of omission and exclusion. The carpeting of the urban landscape by single family zones has resulted in a scarcity of available land for higher density development, and by extension, the lack of availability of affordable housing today — exacerbated by the opposition of the current residents of those very same zones, for whom proximity is often viewed as a threat to the separateness they view as essential to their quality of life.

Ironically, the isolating effects (working from home, etc.) of the current global health crisis have served as an unlikely agent in exposing the self-induced pandemic of social isolation that has resulted from the above mentioned zoning policies — having been in the making over the past half-century, masked by single-family zoning’s myth of neighborliness and sociability (one generation’s sanctum is another’s solitary confinement). Today’s exponential surge in homelessness is long-in-coming testimony to the shocking degree to which mental illness has come home to roost due to such policies. But it is equally symptomatic of the absence of new housing solutions to proactively remedy it, a result of the cognitive dissonance that was an unintended consequence of our collective cultural desire — fed by mortgage lenders — to fulfill the unconditional promise of the American Dream: namely, to “have it all,” and to ourselves.

Learning to live together — by designIf there is a silver lining to the COVID crisis beyond simply exposing the tenuous line between loneliness (at home) and mental illness (on the streets), it may be in the emergence of new habits and formats of small-scale socialization in the domestic sphere, in lieu of the availability of conventional locales such as offices, gyms, and restaurants.

This has seeded a newfound appreciation for collective life — our fundamental interdependence — witnessed in acts of kindness to the elderly, poor, and immobile: food banks and co-ops, grocery delivery by neighbors, organically-formed childcare, and home-schooling pods are just a few examples. Indeed, the sharing of space, resources, and experiences — typically considered more a product of needs than wants — has come to instead be valued as a source of social and economic enrichment, surprisingly resuscitated as a qualifying feature of community and urban life.

Crisis-bred innovationThese emerging social practices and behaviors offer fertile ground for innovation in multi-unit housing, regardless of income level. The shortage of affordable housing in cities like Los Angeles is no excuse to consider the reduction of cost as sufficient to excuse both developer and architect from rethinking the problem of housing beyond simply the sum of its parts/units.

At least as significantly, it presents an unprecedented opportunity to improve both the quality of residential (and perhaps now work-from-home) life, as well as that of our urban neighborhoods. More than the unproven savings promised by off-site construction, new typologies of communal, semi-private space that support a more layered and varied collective residential life constitute a powerful strategy to reduce costs and lower rents through the sharing (rather than duplication) of resources, amenities, and services.

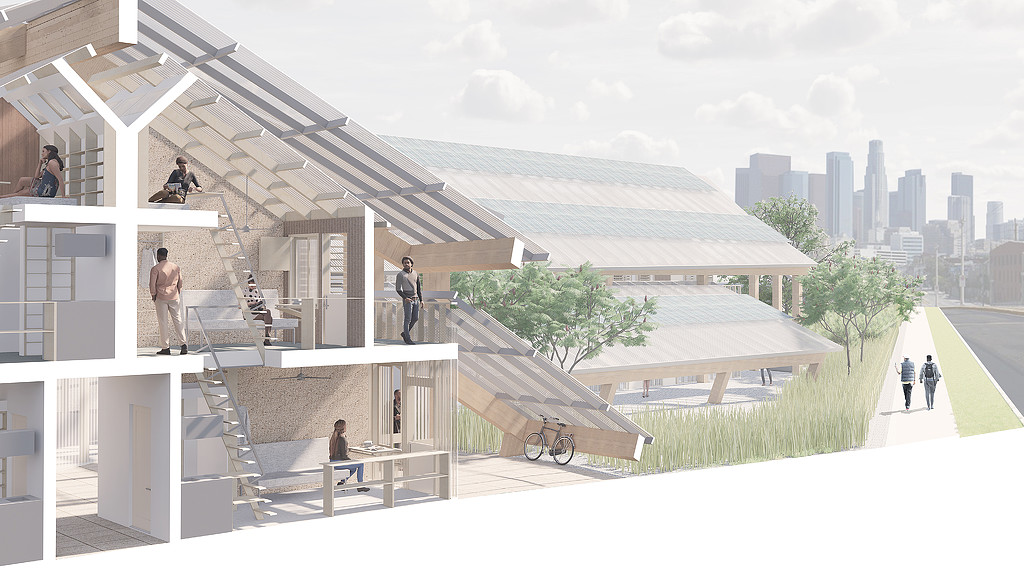

With this in mind, Gensler’s Los Angeles office developed a new constructional, environmental, and social model of affordable housing called Urban Awning. “Awning,” which serves not just the homeless, but a range of populations, focuses on providing a variety of small but dignified indoor units that are supplemented with outdoor communal and dining spaces — all residing under a large roof that features solar shingles on its south-facing slope and translucent fiberglass on its north-facing side. Inspired by California’s indoor-outdoor lifestyle and the vernacular of postwar ranch houses, this prototype — which can be built ground-up or as a retrofit to an existing warehouse — represents a new model of affordable, communal living.

By thoughtfully unpacking the amount of space dedicated to the private domain to allow for regular or serendipitous encounters with neighbors and others over the course of a given day or week, Awning recalibrates the balance and relationship between public and private in favor of establishing a new model of community as much as of housing, choreographing the social life of residents.

If successful, it and other such “experiments in modern living” (to borrow from L.A.’s eponymous Case Study program) have the potential to achieve nothing less than demonstrating/piloting new ways in which we might enjoy — and even learn — the art of living together again, as the silver lining in the challenge posed by increasingly constrained availability of land that is the lasting legacy of sprawl its isolating effects.

For media inquiries, email .