Education

The Crossing at University of Kansas Master Plan

Confidential Education Campus

University of California, Davis Segundo Infill Housing

Purdue University Mitch Daniels School of Business

CSULB Hillside Gateway

Wichita State University Campus Master Plan

Jewish Leadership Academy

Western Oregon University Student Success Center

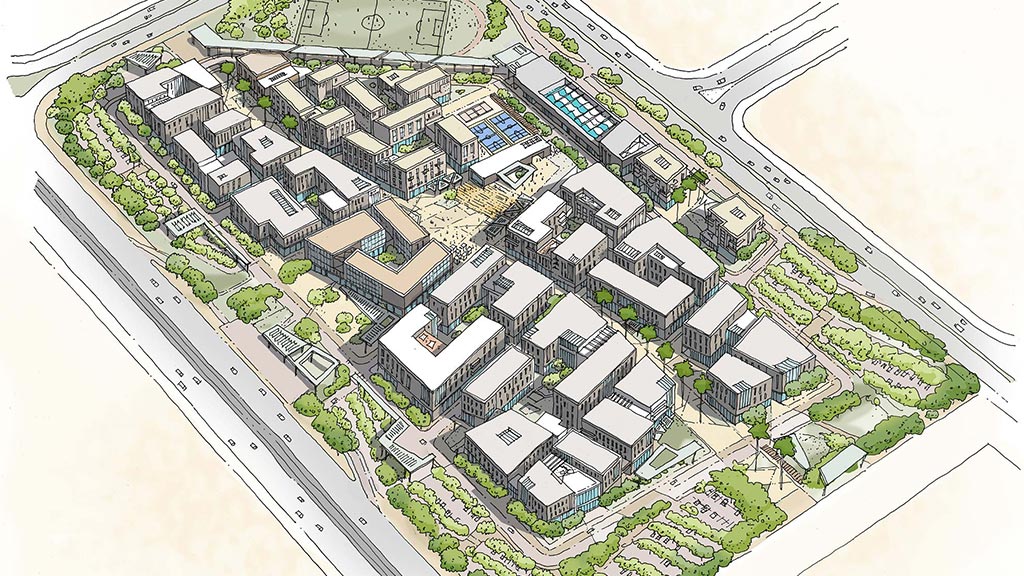

Qingdao Rehabilitation University

UT Tyler School of Medicine

Kent State University, School of Fashion

Del Mar College Oso Creek Campus

Roots to Success

Wichita State University Barton School of Business

West Virginia University Reynolds Hall, John Chambers College of Business and Economics

The Engine at MIT

UCR Student Success Center

CSULB Parkside North Residence Hall and Housing Administration Building

Western Kentucky University Commons at Helm Library

Blinn College RELLIS Campus Administration Building

Tsinghua University School of Economics & Management

Tarrant County College Northwest Campus

Southwestern College Student Union

Friendship Foundation Campus

WPI Unity Hall

Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Heights Branch

Chapter 510 – Swan’s Market

Strategic Services

Our interdisciplinary and integrated team of architects, planners, designers, and strategists partners with clients to develop engagement strategies, educational planning, campus planning, and education design projects. Our expertise includes academic workplace design, space analytics, brand design, and change management.

Campus Planning

We collaborate with clients and communities to develop high-quality environments that respond to the aspirations and needs of users. Our campus planning approach is guided by research and an understanding of what makes an attractive place while responding to site-specific conditions and addressing sustainability.

Programming and Pre-Design

We generate innovative solutions that affect real transformation to support our clients’ visions and long-term strategies. We gather input from stakeholders to articulate a vision, define goals, build consensus, overlay the formative qualities of the site, and measure against budgets.

Architecture

Architecture is always in service to its institution and can elevate experience. Rather than employ a particular style or off-the-shelf solution, we create designs that respond to programs that sharpen, and even recast, the longstanding purpose of a place.

Interior Design

Our interior designers work collaboratively and strategically to deliver innovation, quality, and sustainable performance across various space typologies. We specify presentations and approvals throughout the process to ensure each design satisfies and reflects our clients’ unique missions and visions.

FF&E

As the world’s largest specifier of furniture, we understand that it must serve current and future generations and be adaptable to changing functions. Our specification process is centered around defining the space to select furniture that fits both the project and overall aesthetic.

Brand Design and Environmental Graphics

We integrate graphic design, signage and wayfinding, and architectural placemaking to create spaces with meaning and purpose. Gensler’s Brand Design practice provides specialist designers, strategists, and programmers to create a seamless user experience and unified brand impression.

Sustainability

We integrate sustainable design across our projects and all facets of service offerings to reduce energy and enhance wellness, performance, and quality of life. Teaming with our engineering partners, our holistic approach to sustainability focuses on net-zero, passive strategies, efficient systems, and renewable generation.

Building a New Temporary Home for Pali High

Libraries: The Last Urban Oasis

How Strategic Partnerships Are Shaping Academic Campus Development

The 18-Hour Campus: Strategies for Creating Vibrant, Round-the-Clock Hubs

How Design Drives Innovation in Education & Science

Why Now Is the Time to Double Down on the Promise of California Community Colleges

The Campus as a Catalyst: Combining Student Needs With Institutional Goals

Insights Into the Pandemic’s Impact on Student Well-Being

Inclusive Design for the 21st Century Library

Learning on the High Street: A Vision for the Future

A New Tool Helps Organizations Maximize Their Community Impact

Are Educators and Campus Staff Ready for an Unassigned Workplace?

How Urban Design and Educational Spaces Can Combat Child Loneliness

What Gensler’s Education Engagement Index Reveals About the Future of Hybrid Learning

A Football Academy Designed to Empower Youth in Ghana

Reimagining underutilized campus buildings leads to financial and environmental success.

In the face of limited resources, evolving space needs, and aging buildings, institutions achieve their strategic goals by leaning into adaptive reuse strategies to reimagine the spaces they already have.

Higher demand for workforce preparedness drives design for interdisciplinary spaces.

More multifunctional spaces will support the type of interdisciplinary programming and preparations students need to enter the workforce. Flexible design solutions allow educators to reconfigure spaces for different needs.

Schools focus on student well-being and the spaces they need to succeed.

Campus environments that support the whole student, including spaces that facilitate academic focus, social gathering, and emotional well-being, will improve students’ sense of belonging and overall success.

Deborah Shepley

Mark Thaler

CSULB Unveiled a Major Renovation of Its University Student Union

Three Gensler Architects Elevated to AIA College of Fellows in 2025

The Ironworkers Local 63 Training Center Is “Intended To Capture the Unique Character and Attitude of the Ironworkers Local 63 Members”

Western Kentucky University Commons at Helm Library Recognized As 2024 ALA/IIDA Library Interior Design Awards Winner

Friendship Foundation Campus Will Provide Opportunities for All Abilities To Learn, Explore, and Find Their Place

Gensler Partnered With Western Kentucky University To Reimagine the Helm Library

Designed by Gensler, Frisco Public Library Opens as the Sixth Largest Library in Texas

How Public Libraries Play an Outsize Role in Supporting Local Communities

Key Strategies for Designing Academic Research Institutions That Stimulate Innovation

Machinaka Library, Designed by Gensler Tokyo, Was Recognized With Top International Awards for Its Interior Design

Gensler

The West Coast University Campus Provides a Connected and Energized Campus Experience

Brooklyn Public Library Opens Its New Gensler-Designed Brooklyn Heights Branch