Creating Transit-Oriented Communities in Los Angeles

By Dylan Jones and Jaymes Dunsmore

This piece was originally published at Meeting of the Minds.

Los Angeles is currently implementing the most ambitious transportation improvement plan in North America. At the same time, the region is undergoing an equally significant transformation in the planning, design, and development of the neighborhoods now served by transit. When Phil Washington took the helm of the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority in 2015, he shifted the language about transportation and land use in a subtle and profound way. He spoke about connecting transit-oriented communities — not transit-oriented developments. This has been a critical shift in the way we think about transportation investments, land use, and development in Los Angeles.

With traditional TODs, that may feature mixed-use buildings at or adjacent to a public transit station, the focus is on the development made possible by the public investment. A transit-oriented community takes a more holistic view, recognizing that neighborhoods surrounding transit stops are complex ecosystems that deal in physical form (buildings and infrastructure), mobility dynamics (how people get around), and finally social resiliency (community justice). TODs are development projects, while TOCs are neighborhoods, comprised of many voices, many desires, and many complex challenges.

What makes a successful transit-oriented community?

While each transit-oriented community is unique, there are several common features that most successful TOCs share:

- Public-Private Collaboration

- First-Last Mile Connections

- Community Engagement in the Planning Process

In Los Angeles, the city and the transportation authority have both embraced these three principles as they work to expand transit and improve mobility across the region, creating a model for sustainable urban development.

Public-private collaboration

Creating successful transit-oriented communities requires collaboration between transit providers, municipal governments, and private developers to capitalize on the value created by transit infrastructure. LA Metro’s Joint Development program and the City of Los Angeles TOC Affordable Housing Incentive Program are two examples of how communities can leverage public/private partnerships to develop the housing, office, and retail spaces needed to create a walkable, transit-oriented community. Metro’s Joint Development program is focused on developing Metro-owned property in order to support the agency’s broader policy goals, while LA’s TOC Program serves to incentivize development of privately-owned parcels near transit stations.

The largest Joint Development currently in the works is located at the North Hollywood Metro Station where the Orange Line BRT connects with the Red Line Subway. The 15-acre site is currently used as a park-and-ride lot and one of the busiest Metro hubs in the system, witness to over 28,000 daily boardings. Following an extensive local outreach effort led by LA Metro, Gensler worked with private developers to prepare a development framework plan and vision that includes approximately two million square feet of housing, office, and retail space. The plan includes a 25% affordable housing goal, new transportation infrastructure, and significant open space. The project offers a new urban experience in the heart of the NoHo Arts District, an area historically subject to suburban sprawl.

Likewise, the TOC Affordable Housing Incentive Program works to leverage transit investments to support the production of affordable housing around transit stations; however, the program has been most successful in supporting smaller-scale projects. Recently approved projects include a multi-family development in West LA, which was increased in size from a five-story, 51-unit project to a six-story, 65-unit building with ten affordable units; and another in the Sawtelle neighborhood, which added 15 additional units in exchange for designating eight affordable units. The incentives are tiered to both the type of transit station (i.e. rapid bus, light rail) as well as the proximity to the station itself, allowing projects which otherwise would not include affordable housing to build more units at greater heights with reduced parking in return for providing income-restricted units.

First-last mile connections

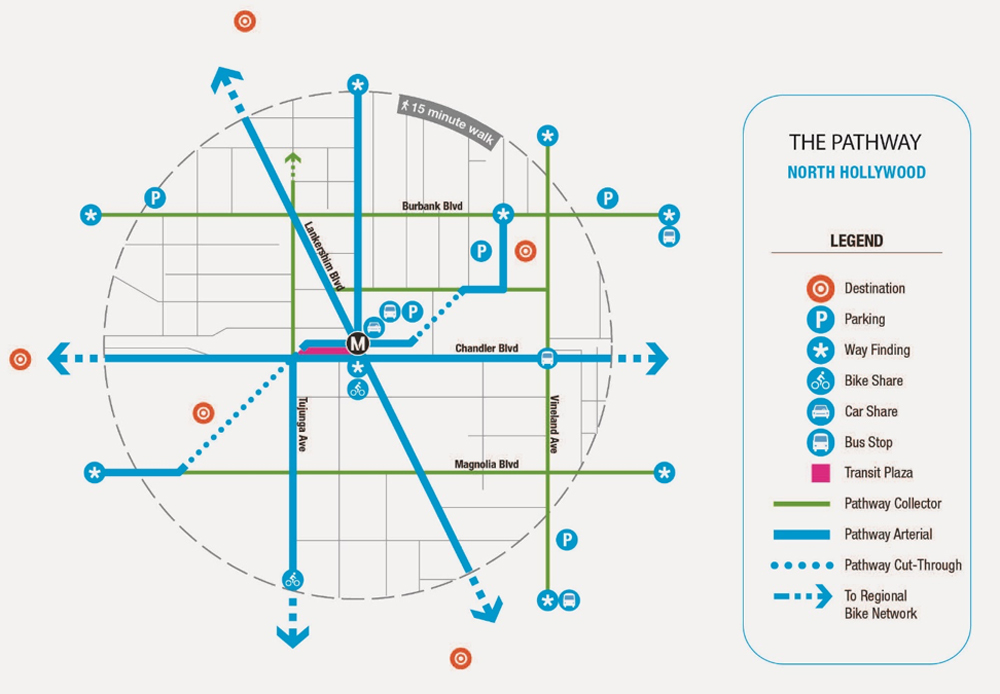

Successful transit-oriented communities incorporate infrastructure improvements that extend beyond the station or project site, creating first- and last-mile connections that enhance access and mobility for the surrounding neighborhood. It is well known in planning policy that individuals are willing to walk up to fifteen minutes to access transit. That translates to one half mile in a perfect world with no barriers (i.e. streets to cross). That same person can travel two to three miles in the same time on a bike or electric scooter.

Metro has been at the forefront of active and new mobility planning nationally since adoption of the Metro First Last Mile Strategic Plan in 2014, which was the nation’s first planning policy that identified and responded to the proliferation of new active and micro-mobility modes. Recognizing that the vast majority of transit riders walk or roll themselves to stations (relatively few drive and park), the First Last Mile Plan takes a careful look at infrastructure improvements that expand user access sheds and the reach of transit. When developing the TOC Program, the City of LA adopted the same half-mile radius as the basis for the program, underscoring the importance of infrastructure improvements that facilitate travel within that access shed.

The First Last Mile Strategic Plan proposes an infrastructure solution, the Metro Pathway, that supports safe, intuitive, universally accessible, and fun access to transit via protected rolling facilities and bundled streetscape improvements along targeted access routes. The Metro Pathway dramatically increase ridership through an extension of the access shed, and improvements to access quality within the existing shed. The infrastructure provides a “follow the yellow brick road” approach, and provides the public sector with a pragmatic blueprint for supporting a wide range of new mobility options as an extension of public transit.

The North Hollywood Joint Development project integrates these planning principles, breaking down the large existing parcel and restoring the urban block structure in order to reconnect the neighborhood to the station. Metro is currently working on a number of other first-last implementation efforts including Pathway development along the entire Metro Blue Line corridor that runs through South LA from Downtown to Long Beach. The work along the Blue Line has been unique in that it was conducted in partnership with a number of local community based organizations who played an active role in the production of the targeted plan.

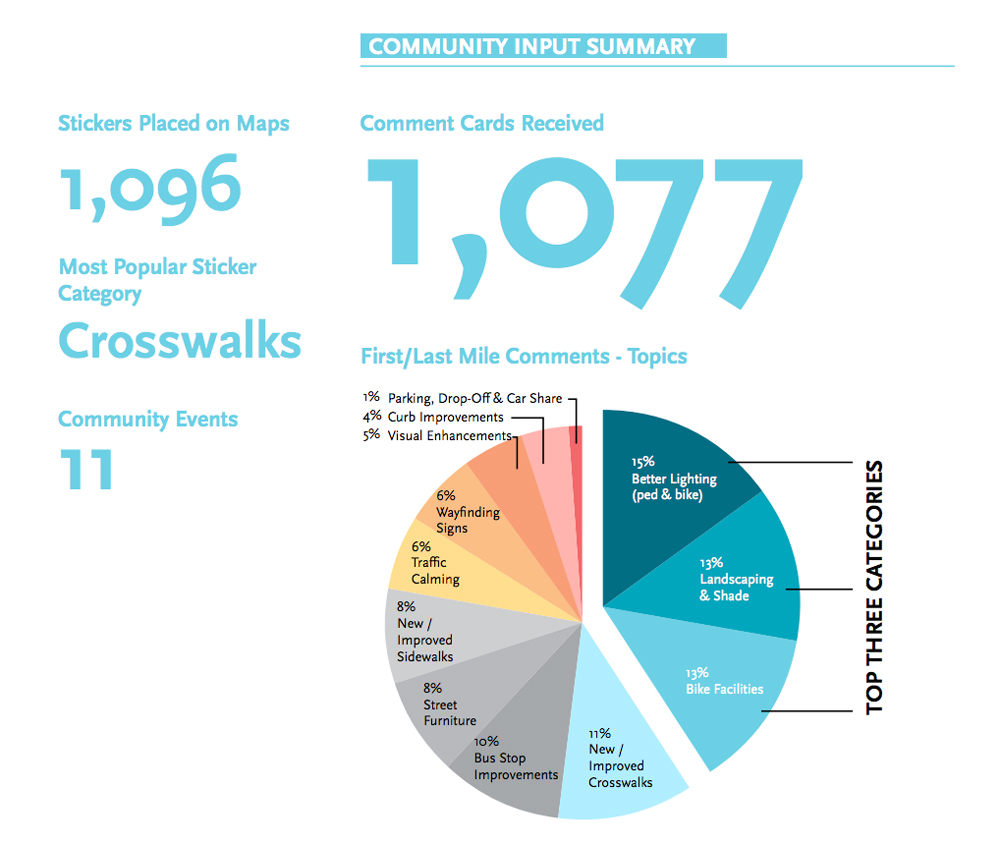

Community Engagement

To be successful, transit-oriented communities need broad support. Metro’s Joint Development program has established a rigorous process for developing properties with controls that support broader Metro policies. Metro undertakes the first step of the process in partnership with the local community, and together they create development guidelines sensitive to local concerns. In turn, Metro has an opportunity to educate residents on the merits of great transit-oriented developments. Metro then moves into a competitive bid process with developers who aim to meet the guidelines in return for a favorable long-term ground lease.

Metro’s process ensures community engagement, adherence to publicly vetted policy, and a competitive bid environment in support of high-quality projects and resource efficiency. Metro has successfully completed over a dozen major joint development projects and has another half dozen currently in the pipeline. Metro’s Joint Development Program, First Last Mile Strategic Plan, and the city of LA’s TOC Program are three policies that support the development of well-planned transit-oriented communities. Together, they actively engage with the extremely complex dynamics that exist between transportation infrastructure and land use. They work to focus on the needs of communities, while being sensitive to local identity and the potentially disruptive nature of heavy infrastructure development. By reframing the transportation/land use language beyond a simple understanding of TODs, Metro and local leaders have allowed for a more nuanced, sensitive, and pragmatic approach to growth and resiliency.

For media inquiries, email .