An Advocate’s Journey: The Role of Design in Enabling Issue Advocacy

By Ryan Cavanaugh

In the design world, there are a lot of buzzwords we hear every day: experience, purpose, disruption... But what about advocacy? We all advocate for something, but as influencers of space we’re uniquely positioned to make the world a better place through the power of design. Physical space can and should be a catalyst for issue advocacy. Space has the potential to inspire, and it can be the gateway that initially connects people to an issue or cause.

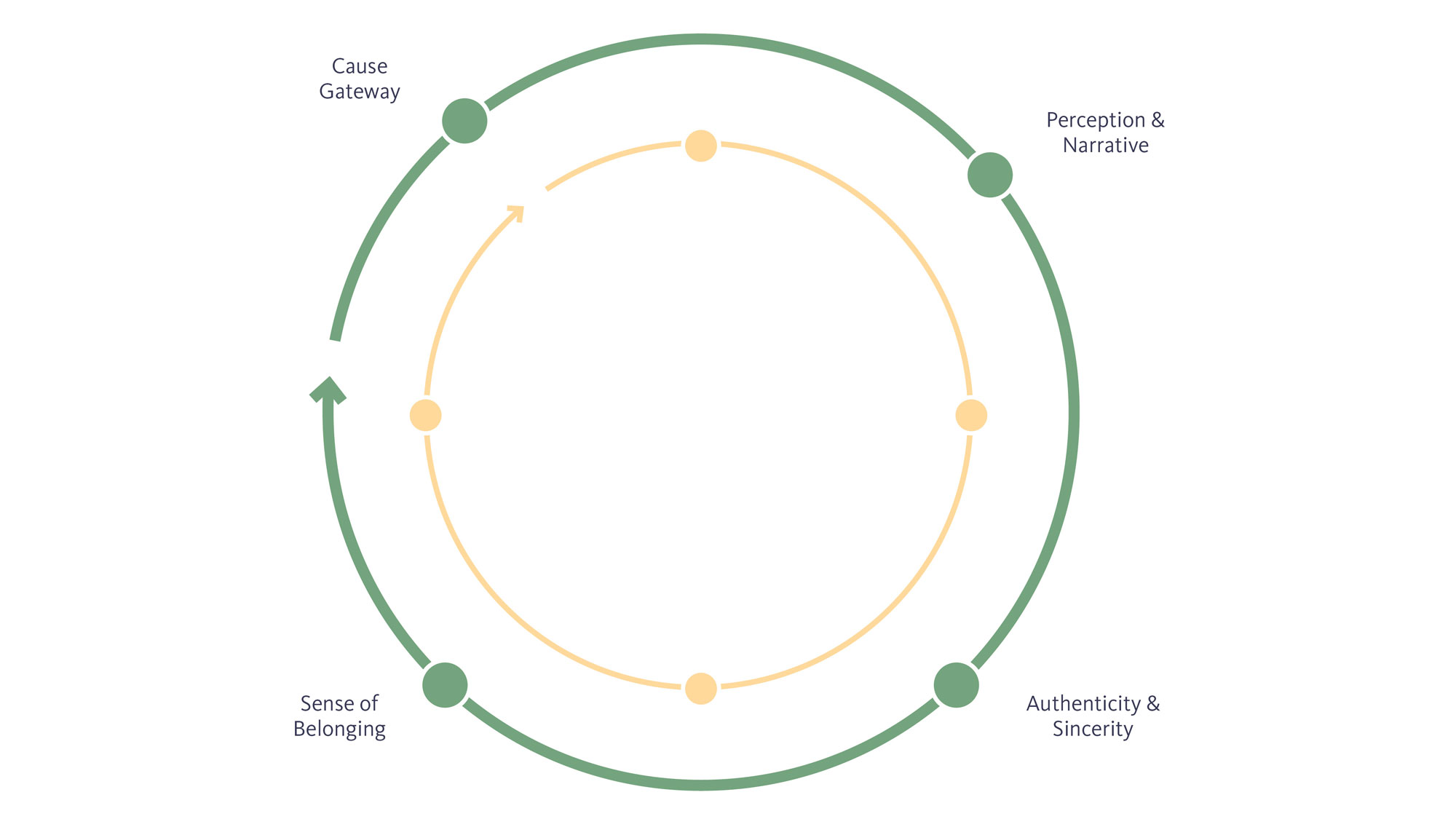

To understand the role design can have, one must first understand what it means to be an advocate, and how to advocate for not just ourselves, but our friends, colleagues, and clients. The advocate’s journey is simple, but profound, and it starts with what we’ve dubbed the "cause gateway." This is the initial moment of interaction where someone is first exposed to an issue. It’s the catalyst that gets them engaged at a personal level, so they can empathize with a topic in an authentic way. After that engagement, they form their own perception around that particular issue and begin to form a narrative, which eventually creates a sincere connection with the issue and yields a sense of belonging. As people become advocates, they also become the cause gateway for others.

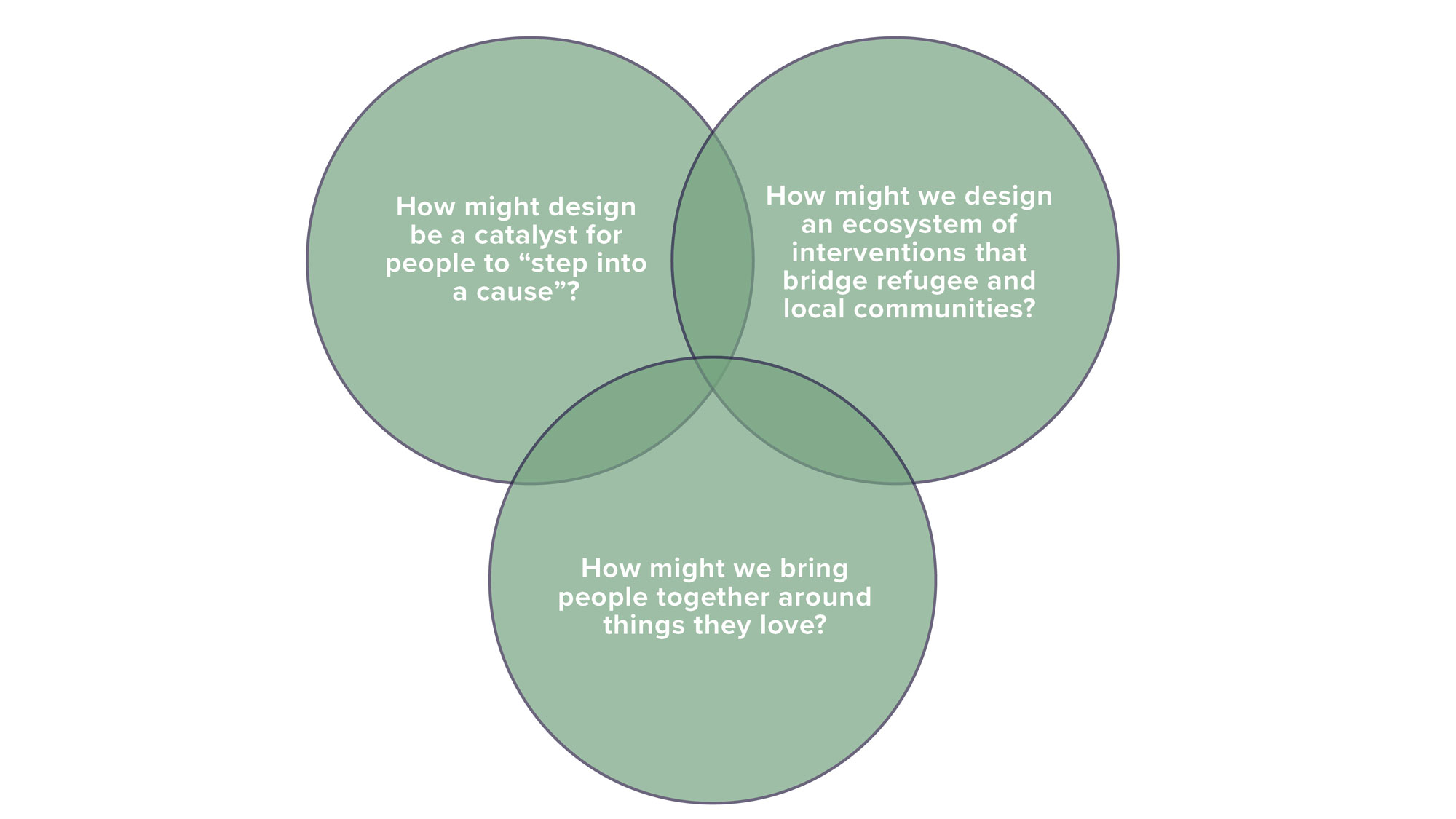

As part of Gensler’s Southeast Emerge program, an internal leadership program that encourages rising leaders within the firm to build outside relationships around a topic of shared interest, our group explored the role of design advocacy. To further analyze why and how space could function as an advocate, we hosted a workshop with a cross-section of for-profit and not-for-profit organizations in the Atlanta area. To facilitate a more specific conversation and extract some universal takeaways, we focused on one specific issue: the refugee phenomenon. The goal was to create a universal set of design drivers, based on the following questions:

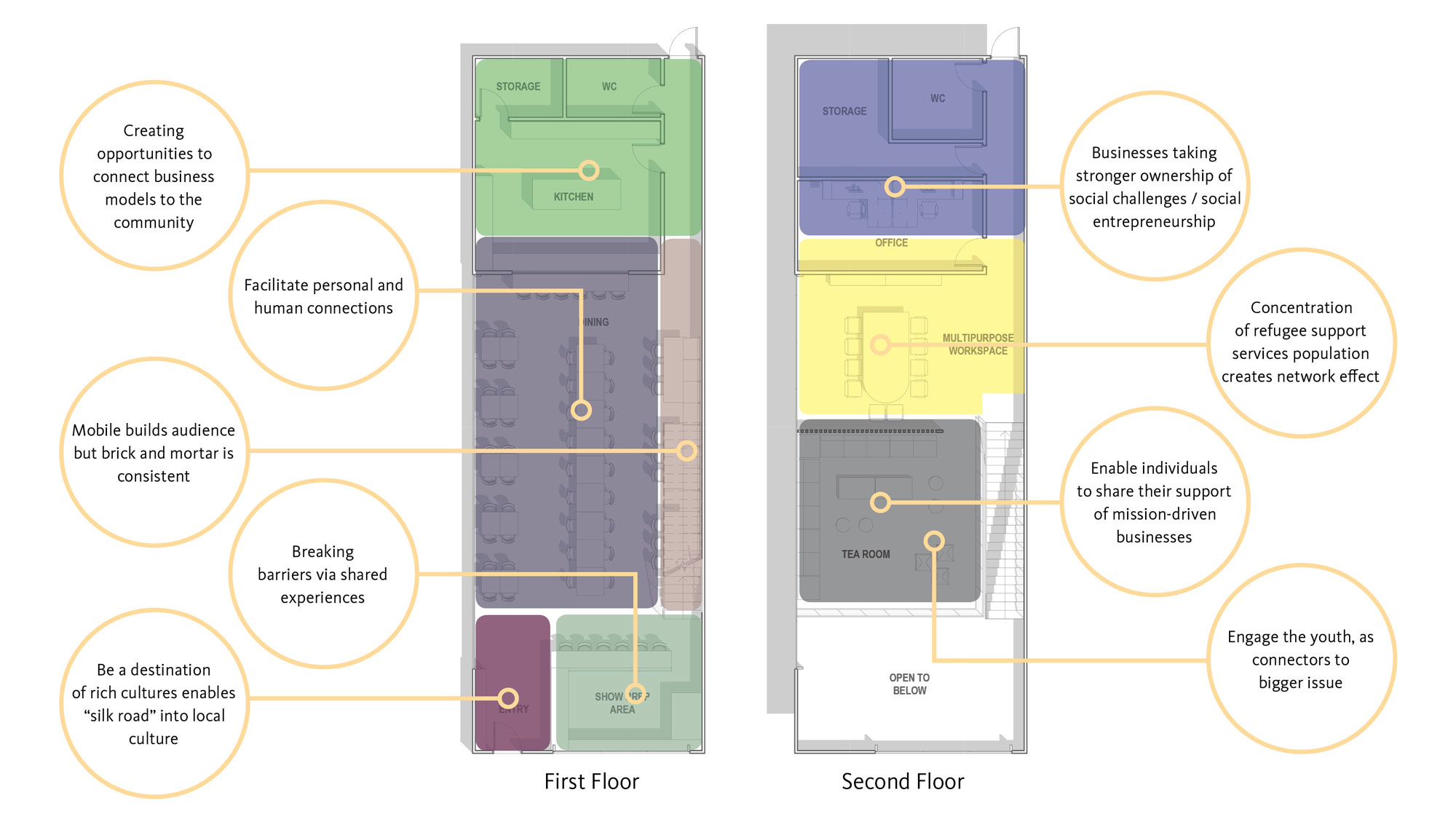

Through this charette, we determined that a physical space could have the potential to:

- Facilitate personal and human connections between friends and strangers

- Break down barriers through shared experiences

- Geographically co-locate and connect with like-minded businesses, organizations, and communities, creating an ecosystem of change agents around an issue

- Support career pathways for those with barriers to employment

- Design with awareness of power dynamics, fostering empathy and protecting those who are situationally vulnerable

- Challenge the marketplace to inspire change

To put these drivers to work, we partnered with a small business in Baltimore called Mera Kitchen Collective, which offers refugee and immigrant chefs a place to cook in the city. To explore our thesis, we designed a prototypical restaurant space for the collective, based on a Baltimore row home location that they hope to one day call home.

We created an inviting and familiar experience that sparks curiosity by putting the bread oven and spices in the front window and at the entry to the space. Inspiring messages and textural materials provide a street presence and invite the public inside. A window to the kitchen frames the chefs as they work and provides visual connection to the art of their craft. Communal seating facilitates conversation and connection, with informal gathering and learning spaces in a mezzanine level. A collage of photos along the stairs to the mezzanine celebrates the Mera Kitchen Collective chefs and contributors who have made this space possible, telling their stories and sharing their dreams for others to be inspired by. A large mural in the double height space highlights the message, “We all see the same stars,” reinforcing the mission of the business and the space.

Mera Kitchen Collective got its name from a play on the Greek word “Meraki,” which means to pour yourself wholeheartedly into something, doing so with soul, creativity, and love. A part of you is embedded in the work you’re doing. When working on spaces that are issue-focused, we have to design in the same manner. Unless we understand and become entwined in the mission, the work will be void of emotion and miss its cue.

We can all inspire change, through actions as simple as being a good friend, or being kind to a stranger. As designers, we have the ability to create spaces that evoke empathy, inspire change, and act as cause gateways in their own right.

To further engage on this subject, check out Gensler’s recent work with Foundations, Associations, & Organizations, or connect with Ryan Cavanaugh to learn more.

Additional contributors to this post include: Paul Samala, Elaine Asal, Anat Gimburg, Meredith Baber, Christian Fortuno, and Michael Adkins.