Second Summer: Adaptable Shading Solutions for Unpredictable Seasons

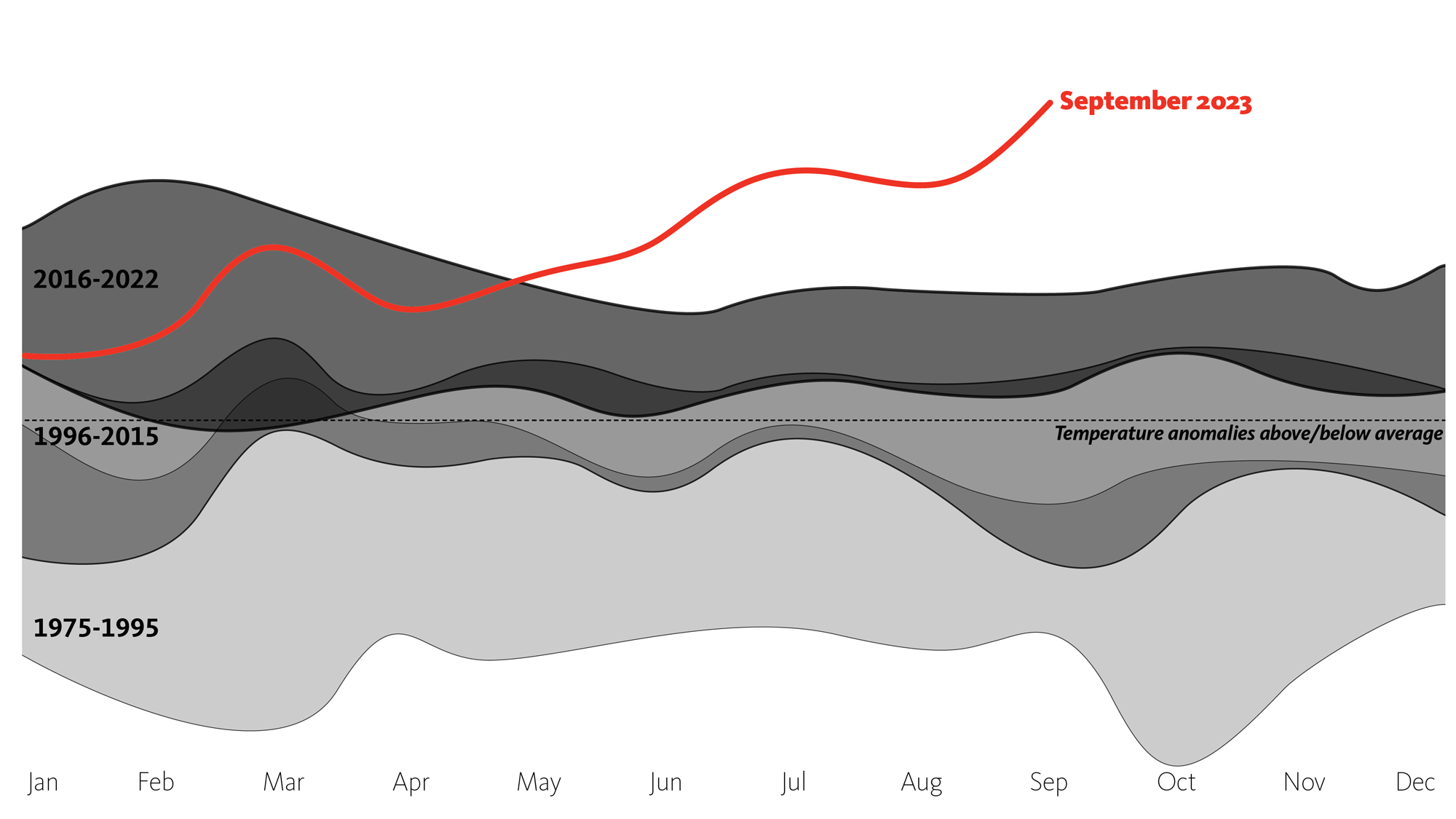

Heat waves and soaring temperatures have recently run amok. In June, July, and August 2023, the planet shattered global heat records month after month, but the latest numbers from September 2023 are even more alarming when we compare them to historical global temperature anomalies from the past 50 years. In the Northern Hemisphere, we tend to think about the summer being the hottest season, with the sun at its apex and the extended hours of daylight. But it’s clear these temperature spikes are not limited to the hottest summer months.

No matter how much our climate changes we can still predict exactly where the sun will be at every moment of every day — assuming of course that nothing interferes with our waltz around the sun. Designers use this information to thoughtfully arrange building features that shade us from, or welcome in, the sun’s light and associated warmth. It does not, however, help us with the apparently increasing discrepancy between the solar year and the thermal year.

The solar year is tied to our orbit and our calendar for as far back as we can track both. The thermal year has always been out of phase with this stable geometry. The mass of the planet takes time to heat up so that we regularly do not reach our peak temperature until one or two months after the day of maximum heating. On a smaller more accessible scale, a pool will not reach its highest temperature from the sun’s impact until a few hours after solar noon. Our current challenge is not with the discrepancy between solar and thermal year, that is simply a function of physics. What’s alarming is the increasing gap between the two and how we can address it.

Traditional design strategies have always managed the solar year with some level of effectiveness using fixed shading devices or architectural overhangs. The challenge with this is that any overhang that fully shades us in the summer, will likely provide too much shade in the winter months. Since the advent of air-conditioning, we’ve managed this discrepancy through mechanical means. Continuing to rely on artificial, energy-intensive solutions to manage this expanding gap will result in a cascading impact on carbon emissions. We need to focus on passive solutions and luckily, we have one at hand with multiple execution options, though not one that is often used to its greatest potential.

Captured Movable Shading Devices

Interior shades are a staple of the workplace environment. They allow the occupant the ability to manually modify their environment to promote or discourage the multisensory experience of feeling the suns warmth on their skin. At select moments we motorize these systems but more often that feature is also tied to the user’s desire to control them and not the thermal conditions. High performance buildings take a different view on shading. In addition to our perception of the sun’s radiation on our skin, interior finishes can play a role in the overall temperature fluctuations in the spaces we occupy. Carpet and other soft finishes will absorb solar heat energy and release it quickly into the environment. Stone and other hard and high mass materials will also absorb that energy but retain it for long periods of time creating a cooling effect in the space until the early evening when that additional warmth is desired after the sun sets. Automated interior shades can be tuned to an interior’s unique set of finishes to take advantage of material properties.

Exterior Movable Shades

Dynamic buildings adapt in response to the external environment in a way that makes buildings more flexible and resilient to change. Movable exterior shading devices, either vertical or horizontal, offers a compelling solution through design. These systems can respond better to a dynamically changing environment than fixed elements. During overheated periods of the year, which does not always coincide with the sun’s path across the sky, full shading is needed. Alternatively, underheated periods require greater access to the sun. Our shading devices need to be in sync with the thermal year and we need building envelopes that can adapt dynamically to manage that more effectively. Simple systems can be adjusted manually a few times a year while sophisticated systems can create a visual ballet of movement across the urban skyline.

Natural Exterior Shading

Another option to help bridge the expanding gap between solar and thermal year is vegetation. Most deciduous plants and trees, which shed their leaves in the winter, are in phase with the thermal year as they are more attuned to temperature than the path of the sun. Other benefits of vegetation include the ability to reduce glare, and they create a cooling effect through transpiration from the leaves. While not a perfect solution, since even leafless plants can still create variable percentages of shade based on the species, they do represent an effective way to manage this gap at the first few stories of a building.

We know there are proven heat mitigation solutions in our design toolbox. But as the effects of climate change shatter heat records and shift the boundaries of our seasons, these solutions must continue to adapt and evolve in order to make meaningful impact in our ultimate goal of net zero carbon.

For media inquiries, email .